Yavuz Baydar asks in Ahval « has Turkey entered the new year filled with signals on a « grand finale? »

« With the economic free-fall, the outcome of which is highly predictable and in acceleration, Erdoğan’s Turkey has entered the new year filled with signals on a « grand finale ». The upper echelons of the state are in brewing turmoil, and the unstoppable hikes on inflation are dragging the electorate into sharper mistrust. Turkey’s strongman faces the most critical, existential challenge of his career, which spans nearly three decades, beginning when he was mayor of Istanbul in 1994.

Yet, the overall picture is filled with complications, uncertainties and paradoxes, as he, known as a mature political fox, plans for his next moves to cement his power for another five years – or maybe more.

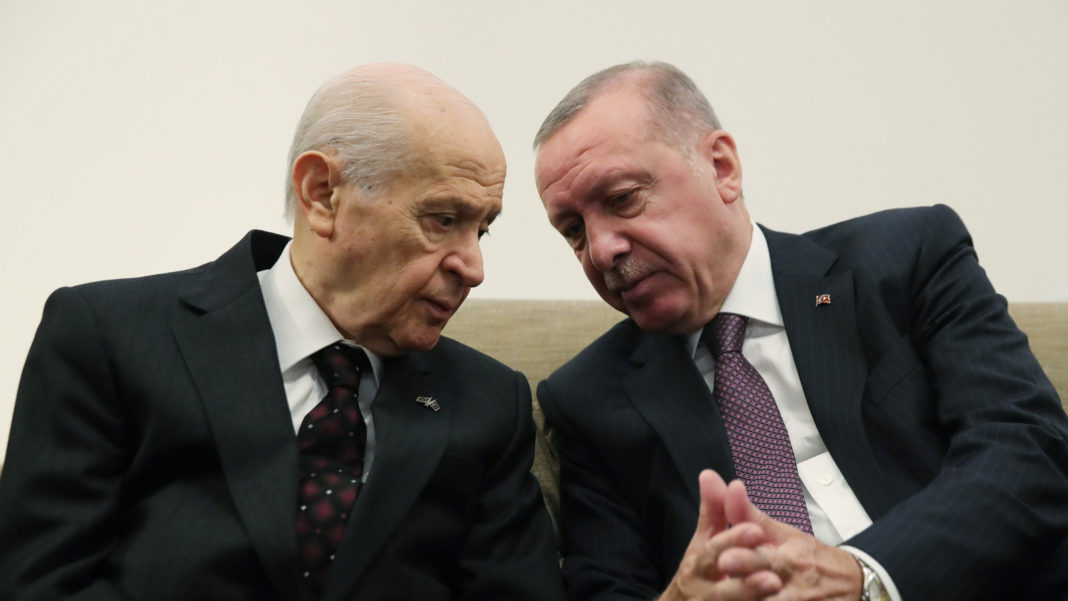

His alliance with the ultra-nationalist Devlet Bahçeli seems well-forged. His control of the – officially dwarfed – parliament remains intact. And his command of the multi-layered security apparatus (including the well-armed formations like paramilitary SADAT, village guards, neighbourhood wardens, staff of the private security firms and the loyal hunters’-shooters’ association) seems unquestionable. To a great deal, the military is restructured to be entirely dominated by Hulusi Akar, acting as a devoted servant to maintain the current power constellation.

To Erdoğan’s advantage is also the ongoing disarray within the opposition. Still challenged by the obsessive clinging to political identities and mired in widespread Turkish nationalism, his antagonists in the centre, the left and the Kurdish segment, have shown a remarkable failure in uniting even against his extremely adventurous economic policies.

Consequently, Erdoğan still sees tangible opportunities to wriggle SADAT himself out of his current troubles and wriggle into the presidency post once more. There should be no doubt that leaving power in the face of profound corruption, abuses of power, systematic violations of the constitution and human rights, will not be an option. Recently, using vulgar rhetoric, he made his intentions clear on the subject.

As the drama intensifies, Turkey will be the country to watch, carefully and without false optimism, this year.

There are seven critical questions at this very stage to shed light on the prospects ahead.

- Will there be elections? If so, when? What is Erdoğan’s strategy?

Erdoğan’s first option is to hold the elections as late as possible. In order to secure a third term in the presidency, he likely has the spring of 2023 in mind for elections, which will have presidential and parliamentary legs. But, he calculates cunningly, in constant consultations with Bahçeli, that if things show signs of turning south – namely, if the economy collapses in his disfavour – he may call for snap polls. In this case, such polls may take place between 45 days to 60. In both scenarios, the Erdoğan-Bahçeli duo will be determined to win by any means necessary.

One scenario linked to things going south is to declare the State of Emergency on two possible grounds: A crisis in the economy or a « state of war ». Both are on the table, given this duo’s obsession with power.

- What do the public polls tell us? How reliable are they?

Unfortunately, except for a few pollsters (such as KONDA and MetroPoll), public surveys are an area deeply polluted with manipulative, partisan « companies » feeding « results » whose methodology is often non-transparent. Very few are reliable. Thus, the findings require a careful read.

What is known, in rough terms, is that the AKP is bleeding severely, more than Erdoğan himself. The former has fallen to ca 30-34%. Erdoğan is losing on « job approval » rates but still ranks higher than his party. We also know that Mansur Yavaş, Mayor of Ankara, and Ekrem İmamoğlu, Mayor of Istanbul, rate above him in the presidential race: Yavaş leads by a 20 point margin, while İmamoğlu is ahead by 10 points. Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, CHP’s leader, lags behind however, by 3-5 points.

Finally, another key phenomenon is that those « undecided » and « protesters » remain unchanged, around 20% in total. Most of those are the AKP voters who distanced themselves from the party. Yet, the large defection from the political parties hasn’t resulted in any gains to the centrist opposition block, formed by the secular CHP and the nationalist IyiP. It can also be read as a clear sign that the defectors from the AKP are now flocked in a « waiting room », with their eyes on Erdoğan. As a pious-conservative segment, they still see him as a the « able » and « saviour ».

- What does Erdoğan have in mind? What is his election strategy to win?

One single point has to be kept in mind to understand the nature of the elections: It is all about who wins the presidential race. The parliamentary leg is far less important, maybe even insignificant. That is because of the ultra-presidential system (which the opponents of Erdoğan see as « the mother of all troubles ») in place since 2017. The system is a de-facto « centralized decree regime », making the elections a « winner takes it all » game.

No bloc, either, seems set for winning a majority in Parliament to change the constitution given the political divisions amongst the electorate. Erdoğan will remain content, therefore, as long as the parties of the opposition bloc believe that winning as many parliamentary seats as possible is more important than agreeing on a common candidate for the presidency.

Thus, Erdoğan is focused on entering the race with the ideal constellation of opponents against him: The more candidates challenging him there are, the better for him. He calculates, apparently, that if in the first leg of the two-legged race, the opposition vote splinters in a way that should divide or alienate the opposition’s voters (for example, Kurds may not vote for Yavaş), he may pull away as a winner.

For this, though, he must « win back » at least 8% of the « undecided », those who distanced themselves from his party but went nowhere else.

- It is easier said than done. Opposition and some pundits seem certain that he will lose, no matter what. Is it not so?

Not quite. Apart from failing to unite and winning the confidence of angered voters, the opposition and its backers have already come under the illusion that such a win is a « slam dunk ». They may be underestimating Erdoğan’s skills: His survival instinct grows as he enjoys casting one crisis upon another to rise out of the mess as the winner. He is far more shrewd than his opponents, and this feature always gives him a lead.

There are two aspects to bear in mind when reflecting on this. First, in laying out the ground stones for a « comfortable » election, Erdoğan (in liaison with Bahçeli) looks determined to get İmamoğlu out of his way by criminalizing him. The latest attacks on the Municipality of Greater Istanbul, on İmamoğlu for allegedly « housing, aiding and abetting terrorists » among the staff is the clear-cut step to remove him from his post and declare him unfit for running in the presidential race.

The opposition sees this as a fantasy but, again, it suffers from not taking into account how deeply Erdoğan penetrated the state institutions. In İmamoğlu’s case (and many others), The High Electoral Board (YSK), subordinated to Erdoğan’s Palace, will be the key player. It is the institution that decides who is eligible to stand for the elections.

There should be no surprise that YSK will be busy annulling a number of names from the opposition candidate lists. Even if the pro-Kurdish HDP party isn’t closed before the elections, YSK will likely eliminate many Kurdish candidates from running.

And its decisions are final. The system is designed to make it impossible to appeal its choices in the Administrative, Supreme Court, or ECtHR. So, keep a close eye on the YSK.

- But this can lead to extreme reactions from the public. What if the people take to the streets?

Erdoğan is a keen watcher of Venezuela, Belarus, and, most recently, Kazakhstan. If people pour out to streets, he will be content to respond with full force, declare a State of Emergency and postpone the elections through a single decree.

- What about the election day? Will there be « safe elections »?

Not likely at all. As long as Süleyman Soylu remains as the Minister of Interior, the results of the elections will be in grave danger. Despite scandalous accusations on corruption and alleged « organized crime » linkages looming over him, this politician, a protege of Bahçeli himself, refused to resign. In simple terms, Soylu is the most proper actor obstinately kept to serve current the power structure. And he, in command of a massive security force, will do whatever he may be told to do to oversee the « safety » of the elections to secure a favourable outcome for Erdoğan.

And the remarkable part is that despite the persistent concerns in Ankara, the opposition has not (yet) launched a campaign to have independent caretaker ministers in the Department of Interior and Justice for legitimate surveillance of the polls.

- The key issue is that Erdoğan has no « exit strategy ». Is amnesty or permanent immunity from prosecution (like some autocrats established before their departure) possible?

Contrary to some pundits who recently suggested this was a prospect, it is, in fact, nearly impossible. In Erdoğan’s case, such talk is redundant.

First, he has clarified that « he is in it until the very end ». The record shows that « he is a man of his word » (see his statements on rate/inflation). Second, he is fully aware that his record of corruption, abuses of power, unconstitutional acts and human rights violations constitute a point of no return: The moment he stumbles or leaves power, his antagonists will be all over him. Third, he is an extremely paranoid personality who trusts no one. Fourth, there is absolutely no « wise person » above political divides that he will accept meeting, let alone listen. Erdoğan will fight to the very end, determined to stay in power to stay safe.

Thus, Turkey in 2022 is bound to be in much deeper turbulence than optimists may think. »

Ahval, January 8, 2021, Yavuz Baydar