Duvar English, May, 8, 2021, Kenan Behzat Sharpe

German-born American academic Jenny White’s latest book, “Turkish Kaleidoscope: Fractured Lives in a Time of Violence,” is a powerful attempt to grapple with the violent period of the 1970s in Turkish history, one which she witnessed first-hand. It dives deep into the social conditions and personal choices that caused so many young people to take up arms or join rival political factions in this period.

The 1970s remains a black hole in Turkey’s collective memory. The previous decade of the 1960s was more optimistic and picturesque. Students, workers, peasants, and artists imagined and fought for a better country and world. In the 1960s there were already black clouds of violence on the horizon, but it was in the 1970s that the country really went off the deep end. Animosity between leftists and rightists approached the level of a full-scale civil war. Young people from rival groups shot each other dead in the streets. Meanwhile, unstable coalition governments and economic crisis turned everyday life into a nightmare.

It was into this apocalyptic atmosphere that Jenny White unsuspectingly arrived in 1975 when she moved to Ankara for a master’s degree at Hacettepe University. This German-born American academic’s latest book, “Turkish Kaleidoscope: Fractured Lives in a Time of Violence,” is a powerful attempt to grapple with this violent period in Turkish history, one which she witnessed first-hand.

While certain TV shows like Çağan Irmak’s “Çemberimde Gül Oya” have tried to push the public to reckon with the trauma of the 1970s, popular representations of the period often oversimplify the situation. White’s book skillfully walks the line between the academic and the popular. It dives deep into the social conditions and personal choices that caused so many young people to take up arms or join rival political factions in this period.

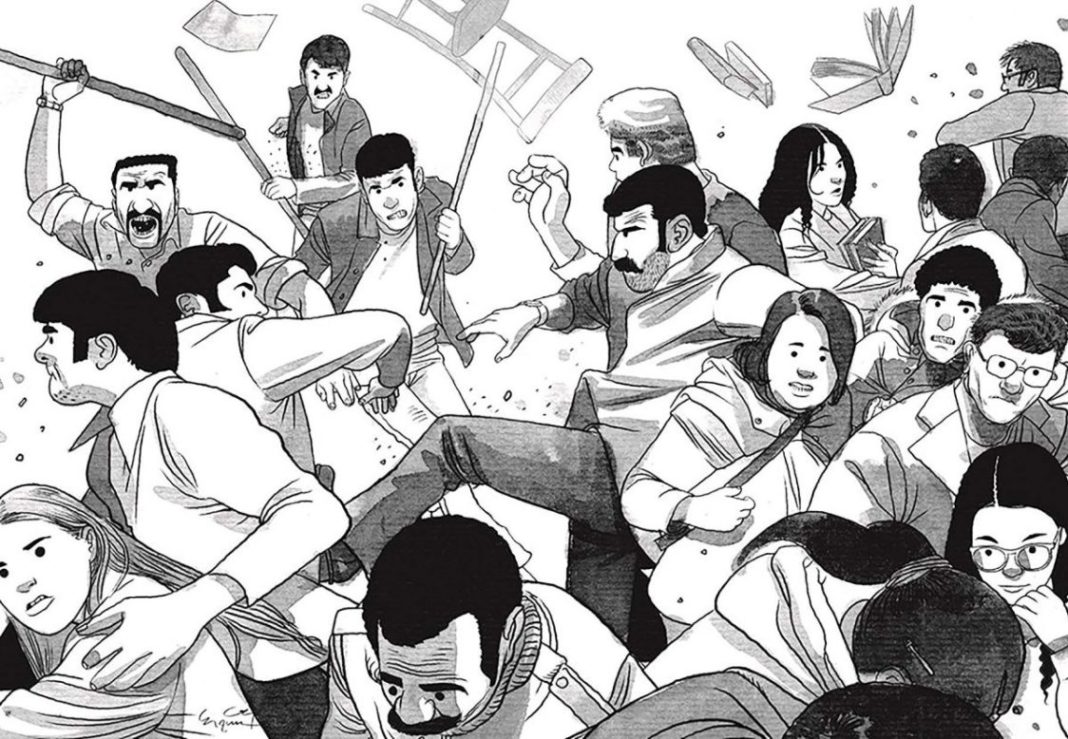

Though written by a social anthropologist, “Turkish Kaleidoscope” is actually a graphic novel. This makes the book both rigorous and readable. It is similar to other graphic novels dealing with social/historical issues like Marjane Satrapi’s “Persepolis” or Özge Samancı’s “Dare to Disappoint.” In “Turkish Kaleidoscope,” gorgeous illustrations by Ergün Gündüz help us see and feel everyday life in the 1970s.

For example, most of us have heard about the battles between left and right in this period. It is one thing to hear statistics about how many people were murdered each day and another thing to see this violence illustrated. In one scene in the book, a university student sits on a school bus. Some men from a rival faction come up and pound his head in with a hammer. They then drag his body out of the bus and throw it into the street. There is nothing abstract about how violence is portrayed in “Turkish Kaleidoscope.” We vividly witness drive-by shootings, bombings, armed clashes in university canteens, and bank robberies.

The book does not show violence for its own sake, however. It allows us to enter the turbulent 1970s through a dramatic narrative centered on the lives of a few main characters. (White herself is not just an academic but a novelist, which helps to explain her ability to draw the reader in through stories.) These characters built on the experiences of people that White interviewed in 2014. While based on true stories, she fictionalized elements of their lives and created composite characters that reveal the dynamics of the 1970s.

For example, there is Yunus from Eskişehir. In the illustrations, he has the full mustache and parka of a Deniz Gezmiş-type. He is committed to the revolutionary cause as a medical student at Hacettepe University, but the authoritarian structure of the leftist organization he is part of gives him doubts. Nuray grew up in a village. Thanks to teachers who were part of the progressive Village Institute program, she read novelists like Yaşar Kemal at a young age and begins to form a picture of the injustices in Turkish society in her head. When she came to Hacettepe, it was natural for her to join the THKP-C (People’s Liberation Party-Front of Turkey).

The book also has central characters from the other side of the political divide. Faruk is the son of a tinsmith from Erzurum. He grew up in a religious and conservative environment. Inspired by his older brother who was a commando for the para-military, nationalist organization the Gray Wolves, he also joined up with the violent far-right when he came to Ankara.

At times the emphasis on character’s lives allows the reader to lose sight of the economic, geopolitical, and historical conditions that shaped the 1970s in Turkey (and not only there—the Turkish 1970s shares much with Italy’s violent “Years of Lead” or far-left terrorism and anti-communist repression across the world). Yet White’s aim, as she wrote in the introduction, was to focus on the personal. She writes: “This book doesn’t give an ideological or event-driven analysis but rather asks more universal questions about what causes people to sacrifice their lives, health, and sometimes families for a cause or for an autocratic leader, to engage in violent acts, and then to endanger themselves further by splitting off from that cause or leader.” In this sense, people not necessarily interested in Turkey can also find something valuable in this book.

But for our purposes, better understanding the 1970s in Turkey can also help us grasp aspects of Turkey today. One of these aspects is factionalism. Speaking about the right-left split, White describes a “tendency for Turkish political life at the time, as now, to polarize and fracture into violently antagonistic groups and sides.” In the 1970s, even within the left there were sub-factions that would fight or kill each other instead of uniting to push back against the right-wing Gray Wolves trying to kill them (often with government support or implicit approval).

Aside from factionalism, there were also a deep conservatism to both left-wing and right-wing organizations. This also continues to mar the opposition today. White notes that when young people joined a political faction, “every aspect of their lives was controlled by an autocratic leader. There was no room for complexity or personal choice. A person’s political affiliation could even be read from their clothing and shape of their facial hair. Women were expected to be asexual soldiers, but also to bring the tea. There was a lack of trust in individuals and no tolerance whatsoever for thinking or behaving differently.”

While one expects this kind of anti-individualism and sexism from the right, it is depressing how much these attitudes continue to pervade the left. In the novel, we see left-wing lovers Nuray and Yunus attacked by a group called the Devrimci Ahlak Zabıtası (Revolutionary Morality Police) for having a relationship without being married. Today, our left-wing moralists are perhaps less directly violent but are no less vocal (particularly when it comes to LGBTQ+ issues).

The 1970s remain an important and even inspiring period in Turkish history, though we must be careful not to idealize it. As the character Yunus remarks in the book, “There wasn’t any joy really, though there was talk of bright horizons, of the glorious future, socialism, but it wasn’t a smiling thing. » If there is ever to be a politics of joy in this country, we will also have to grapple with the tendencies towards authoritarianism, factionalism, and conservatism. Books like “Turkish Kaleidoscope” can help.