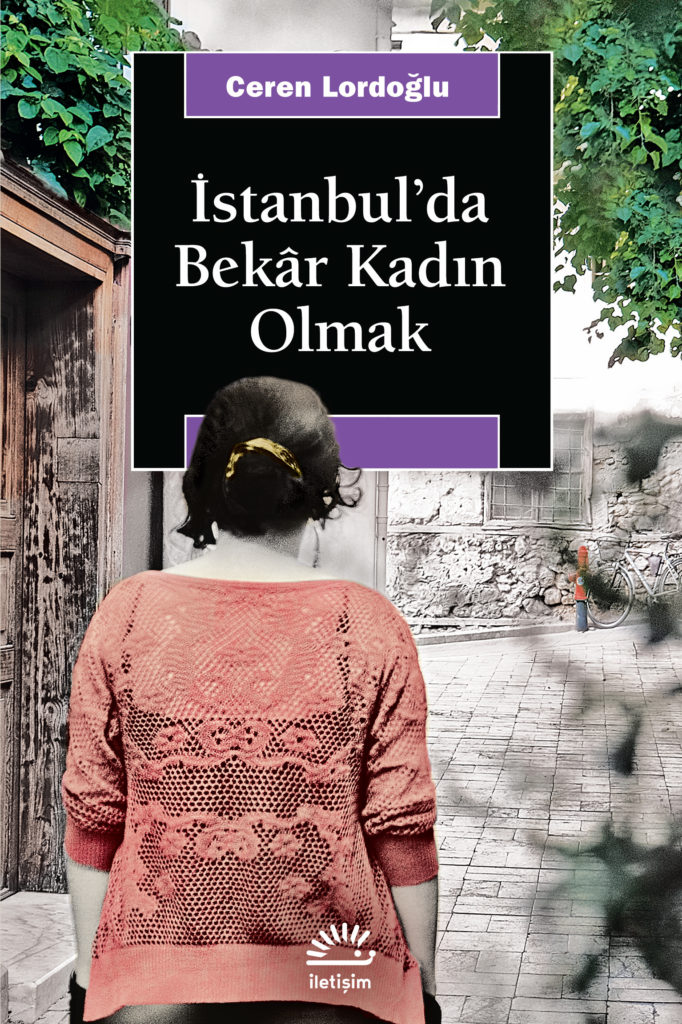

Ceren Lordoğlu is the author of the book entitled Being Single Woman in İstanbul (İstanbul’da Bekar Kadın Olmak), based on her dissertation focusing on the experiences of single women living in İstanbul. The book, published in 2018, analyzes experiences of single women in İstanbul in three different districts and elaborates on the gendered dimensions of the urban space while scrutinizing the notions of neighborhood, security and urban space. Lordoğlu’s academic interest is mainly focused on qualitative research techniques and feminist geography. Hande Gülen, Phd student at the French Institute of Geopolitics (Paris8 University) conducted an exclusive interview with Ceren Lordoğlu for Observatoire de la Turquie Contemporaine. Enjoy the reading.

1. How different single women from the neighborhoods of your field research, Kadıköy, Bağcılar and Sarıyer, respond to different ‘curious looks’ of neighborhoods’ inhabitants or different forms of ‘discomfort of stigmatization’? What are the tactics and the strategies of women to these processes?

While conducting my field research in three different regions of Istanbul, I used qualitative methods. The research group interviewees, which I designated as single, tenant and householder women, told their life stories along with their narratives focusing on their houses, relocations and neighborhoods. Needless to say, as one of the main components of qualitative methodology, I don’t have any representation claim concerning the experiences of the interviewees. However, this methodology has the strength of revealing the similarities and differences between different narratives, so I aimed to make these unseen patterns visible. Moreover, in Istanbul, different class settlements can coexist at the same region, in close distance to each other. In order to see class clustering at the bigger scale, the works of social cartographers based on rental costs can be observed. Therefore, the tactical similarities developed by women living in different regions can arise from this sort of class similarity.

According to my research, single women develop various tactics to deal with the discomfort of stigmatizing. Sometimes they ignore the curious gaze of their neighbors, sometimes they express themselves by courageous reactions and performances (being called as the madwoman of the neighborhood), and sometimes they develop other different tactics. These tactics are often developed within the framework of keeping distance and (if she is married and divorced) not sharing their newly single status within their neighborhood. They vary in a wide range of spectrum: to put the shoes of the ex-husband in front of the house every night and prepare a scene for the neighbors as if he was still coming to the house; not to inform the neighbors about the divorce until the changing surname at the invoice posts get noticed (where the neighbors can see the invoice envelops at the common areas of the apartment halls); to introduce the boyfriend as a relative who shares the house or visits her frequently; in the case of living together as an unmarried couple to wear engagement rings in order to pretend as they are married or engaged; to wear more conservative clothes at the neighborhood and change them when getting closer to the city center where they work.

Unlike in many other European/Western countries, living alone as a single woman is not a common neither an acceptable situation in Turkey. Although the number of women living single in metropolitan areas is increasing every year, the ratio is still very low compared with the Western context. During my field research, almost all women who either left the house of their parents for living alone or living in their own houses after a divorce expressed their single life as an important experience of empowerment and emancipation. The biggest fears of low-income women about divorce, in a city where rents represent considerable amounts, is being forced to be a prostitute as a result of homelessness and being constrained to leave their children to the orphanage due to poverty. Specifically women who are unemployed without any professional experience, raising their children alone were rightfully scared and felt threatened by the high rent amounts of Istanbul. Not only in my work but also in the context of different academic studies and various research reports, women express themselves while answering questions related with divorce in a very similar manner: “Where can I go, if I leave this house? Can I find an affordable place?” Housing and sheltering opportunities depend sharply on the economic capabilities of women with the absence of systematic social aid for the single women in Turkey. Therefore, in all these social and economic difficulties where unsystematic social aids and family networks support are constantly decreasing, to build a separate house is an important component of women’s empowerment. Besides, another striking sign of resistance and power of single women is derived from their sharp decisiveness of raising and educating their children.

One of the most impressive interviews for me was the one that I conducted with a woman who had been subjected to violence from her husband for many years, then divorced him and raised her five children alone. She never worked before her divorce. Afterwards, she began to work at a factory during night shift then in the morning she was coming home and sleeping for a few hours, then again she was going to work to clean the stairs of an apartment with her 4 years old daughter. This woman, despite all the difficulties she experienced told me: “Look! Write this in your book: Women shouldn’t be afraid! We are strong. We don’t have to be exposed to violence. We can do everything by ourselves, also we can raise our child.”

3. In your work, you are emphasizing that a neighborhood means ‘a circle of security’ and a ‘custos morum/guardian of morality’ simultaneously. Women perform various roles and develop a ‘measured distance’, a notion that you elaborated in your work, to stay within the circle of security. How different forms of singleness such as being divorced, having a child or children or being simply single diversify women’s inclusion within such circle?

Measured distance is one of the tactics that single women developed against the curious gaze of the neighbors, as I mentioned above. It is, on the one hand, a kind of boundary making by these women to set distance in order to prevent possible interventions to their lives; and on the other hand, they balance their attitudes for not being totally excluded from the security circle of the neighborhood. Women, therefore, perform in between tight spaces and conflicting motivations in their daily lives, behaving like a wirewalker measuring the distance. Neither do they establish close neighborly relations as they witnessed their parents in the past, nor do they cut off or freeze totally the whole relationship. Women with children, for instance, usually narrow the distance as they need more neighborhood support, especially for the sake of their children’s safety or care. In any case, however, they are aware of the price to be paid while decreasing the distance with increasing social control and more limitations of the neighborhood. I have witnessed that especially women who are supported by the solidarity network of the neighborhood have much more difficulties to build boundaries and set distance with neighbours. An interviewee who benefited from neighborhood’s solidarity network told that her neighbors came to her house for a morning coffee, without asking her availability, in a very embarassed way. On the other hand, I can say that women without children put more distance and have less communication with their neighbors. Although it is very difficult to make generalisations I think single women with children put less distance due to their constant needs for more solidarity network.

4. How would you analyze actual academic milieu in Turkey focusing on urban space and its transformation from a gendered perspective?

In Turkey, number of academic studies both in the fields of the feminist geography and studies focusing on the complex relationships between the urban space and gender regimes increased significantly throughout 2000s. These topics became more popular through this decade. However, it is not possible to identify the gender theme as a research focus or a theoretical paradigm, such is the case with notions globalism, international finance, or neoliberal system, themes with which urban studies deals heavily with. Ayten Alkan’s article entitled “The Weak Link of Urbanism: Gender” reveals the scarcity of studies in this academic field. In particular, the limited number of courses and graduate theses points to the academic gap in gender-related issues in the context of the urban studies. Nevertheless, in urban space studies, it is possible to see a rise of the studies that are more interdisciplinary and enhance the gender perspective.

Share the post « Interview with Ceren Lordoğlu: Being single woman as an experience of empowerment and emancipation »