Appointment of hardline prosecutor Akın Gürlek as Justice Minister signals a brazen judicial clampdown. No wonder why opposition is bound to wither under pressure.

On February 11, 2026, amid a whirlwind day of meetings with parliamentary blocs, the pro-Kurdish DEM Party’s “İmralı delegation,” and Kyriakos Mitsotakis — Greece’s prime minister — Recep Tayyip Erdoğan seems to have made a calculated move that marks Turkey’s passage across another historical threshold.

The appointment of Istanbul Chief Prosecutor Akın Gürlek as Justice Minister isn’t merely a cabinet reshuffle — it’s the installation of a judicial enforcer whose career has been defined by prosecuting dissidents, opposition leaders, and civil society figures.

Totalitarian Consolidation and Constitutional Endgame

With this single decision, Turkey consolidates a hyper-centralized, ruthlessly securitized regime, removing remaining barriers between what exists now and a form of quasi-totalitarian rule, under which the opposition continues to exist as either entities of coalescence or impotent political groups used for window dressing. The appointment therefore marks a brazen escalation in Erdoğan’s quest for unchallenged power.

Gürlek’s résumé leaves no room for ambiguity. As presiding judge at Istanbul’s 26th Heavy Penal Court, he sentenced former HDP co-chair Selahattin Demirtaş to nearly five years for a speech at the 2013 Istanbul Newroz celebrations, convicting him of “terrorist propaganda.”

He handed similar sentences to the late Kurdish politician Sırrı Süreyya Önder (formerly a member of the DEM delegation which visited İmralı Island, where Öcalan is jailed) and to leftist lawyer Selçuk Kozağaçlı, whose 11-year conviction alongside 19 other lawyers from the progressive ÇHD (“Contemporary Lawyers Association”) epitomized Gürlek’s role in criminalizing legal advocacy itself.

Later cases reinforced the pattern: CHP Istanbul chair Canan Kaftancıoğlu received over nine years for social media posts, while Turkish Medical Association (TTB) president Şebnem Korur Fincancı was sentenced to 2.5 years.

Elevated to Istanbul Chief Prosecutor in 2024, Gürlek spearheaded the sweeping probe into Istanbul Municipality, leading to İmamoğlu’s March 2025 arrest on corruption charges critics deem fabricated to neuter a formidable rival. His office indicted İmamoğlu on over 140 counts, potentially warranting millennia in prison, while targeting hundreds of CHP officials amid the party’s 2024 local election triumphs.

As a result, CHP head Özgür Özel faces probes, with his immunity at stake, while jailed mayor İmamoğlu endures what is widely believed to be a farce trial, fracturing the party’s momentum ahead of the 2028 polls. Gürlek’s elevation ensures that prosecutions multiply — from corruption charges to “terror links” — paralyzing CHP’s organization.

His trajectory therefore embodies Erdoğan’s “lawfare playbook”: cementing a judiciary tailored to shield the regime and dismantle its foes.

Mind you, Gürlek’s appointment isn’t about a snap election — Erdoğan has no intention of calling polls before late 2027 at the earliest. Rather, it’s about methodically paving the electoral landscape, ensuring no judicial “cracks” appear that might create legal precedents favoring the opposition.

As journalist Alican Uludağ notes, the appointments signal preparation for 2028 and a new constitution that will not only protect Erdoğan’s seat but constitutionally entrench his political ideology and secure a regime structure.

Thus, the most important aspect of it all:

Now, as Justice Minister, Gürlek automatically becomes president of the Council of Judges and Prosecutors (HSK), granting him sweeping authority over appointments, promotions, relocations, and disciplinary actions for every judge and prosecutor in Turkey. This isn’t a reward for past service — it’s the installation of a gatekeeper to ensure judicial compliance with the regime’s imperatives.

The Dual Strategy: Crushing CHP, Baiting DEM

Historical parallels haunt this moment. A common thread in the past century’s dark regimes was that autocrats who left nothing to chance enjoyed longer political lives.

Against that background, Erdoğan’s move comes paired with a sophisticated “dual grip strategy” targeting Turkey’s fractured opposition.

On one front, the secular Republican People’s Party (CHP) faces relentless legal assault. Following the party’s stunning victories in the March 2024 local elections, the government has arrested mayors, launched corruption probes, and even attempted to annul the CHP’s 2023 leadership congress.

So, no surprise: CHP leader Özgür Özel’s immediate reaction to Gürlek’s appointment — “our job just got much harder” — signals the party’s recognition that a “Category 5 legal hurricane” is bearing down.

On the opposing front, a seductive ploy is deployed toward the pro-Kurdish DEM Party: Erdoğan and his ultra-nationalist ally Devlet Bahçeli dangle the prospect of Kurdish leader Abdullah Öcalan’s freedom before the party.

As a result — apparently on the “wishes” of Öcalan, which are perceived as directives — DEM cooperates with the government’s “Terror-Free Turkey” framework, accepts only rhetorical concessions, and gives up on its traditional demands for collective rights. It is told to expect few counter-gestures but to cooperate with the power bloc on constitutional amendments that will aim to secure the continuity of the hard-core regime — and the party may eventually see Öcalan released or his conditions eased.

Erdoğan himself declared on January 11 that “this term, the new constitution work will be completed,” revealing that a working group in his party is already preparing a draft — namely, one designed to ensure that he can run for the presidency once more without legal hassles. For this, the ruling bloc badly needs the support of the 57-seat DEM group.

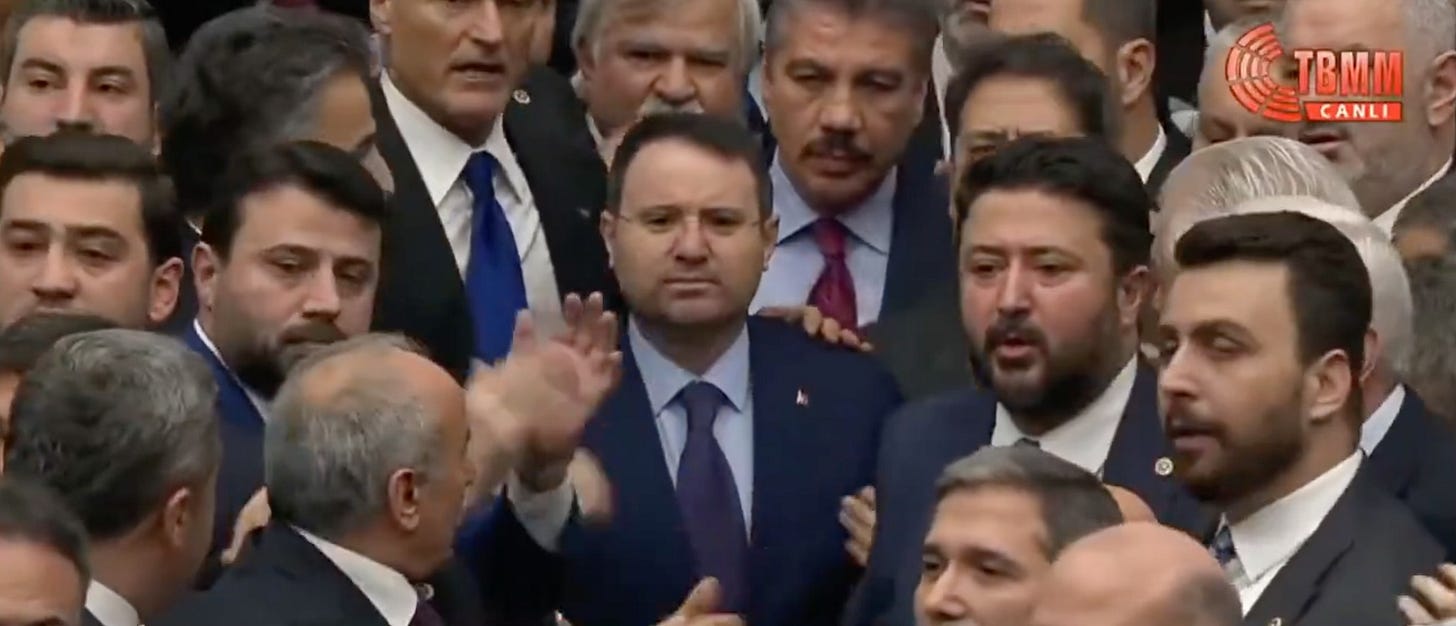

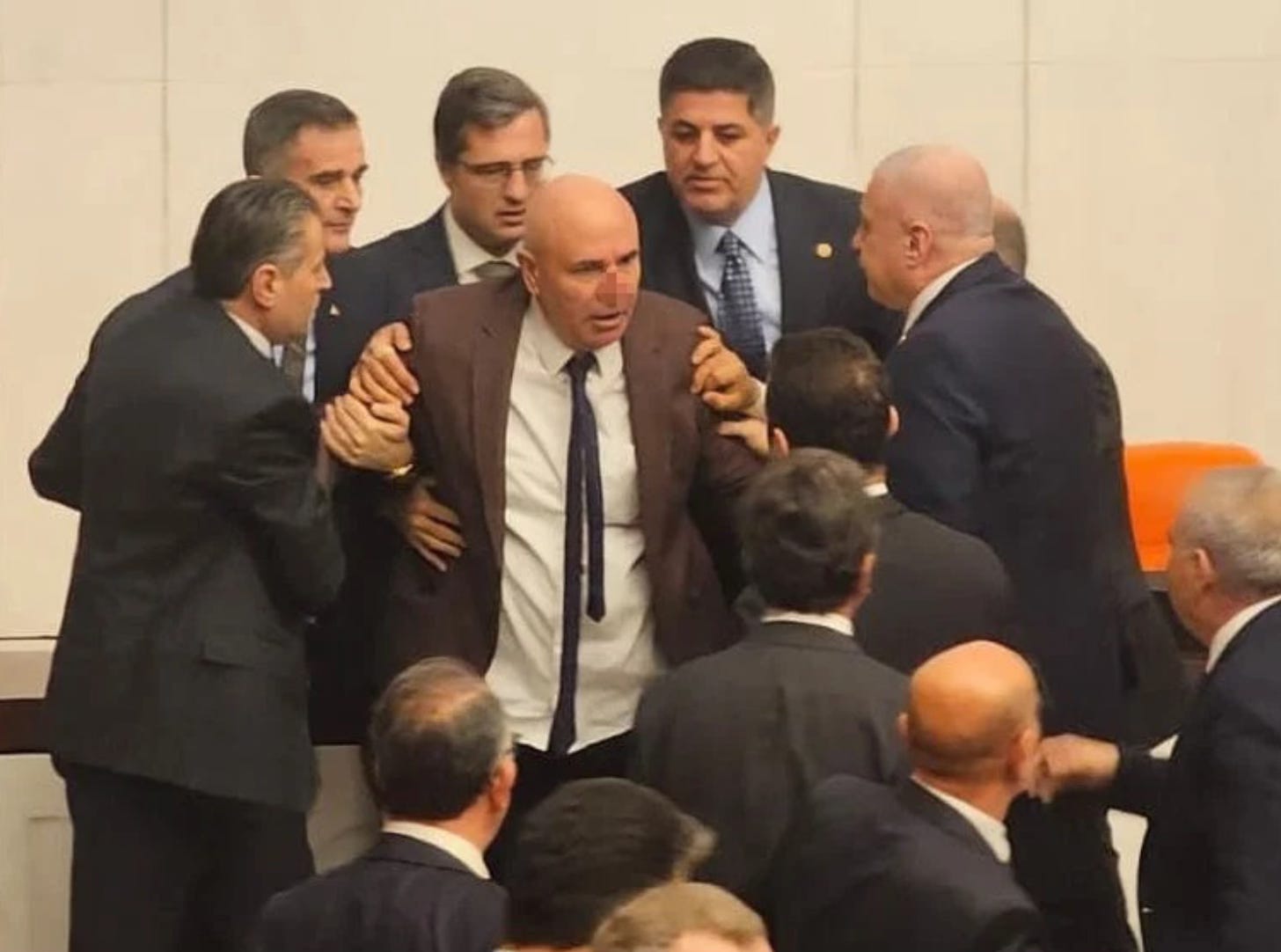

Irony in a chaotic day: DEM’s “İmralı delegation” met with Erdoğan the same day Gürlek took his oath — a choreographed contrast to the massive brawl between CHP and ruling party MPs that erupted on the parliament floor just hours earlier.

The symbolism was stark: CHP members nursing bruises from fistfights while DEM representatives smiled beside Erdoğan in photo ops, as though Parliament operated at “Swiss-level civility.”

The two largest opposition parties, once potential allies that conveyed hope, now follow diverging paths — CHP facing existential legal warfare, DEM ensnared in a regime-controlled “peace process” that risks transforming them into a loyalist fig leaf.

This judicial hammer on CHP, velvet glove to DEM — exploits fissures. Amid a deepening economic crisis that leaves the poor masses with a weakening purchasing power, CHP’s secular base recoils at Kurdish concessions, while DEM is bound to battle to keep its increasingly confused and — because of the retreat of the Kurds in Syria — angered grassroots.

Erdoğan’s MHP allies amplify the rhetoric: demonize CHP as “rotten to the core,” bait DEM with a “Kurdish opening” mirage. Result? The opposition fragments, echoing Azerbaijan’s managed pluralism — or Central Asian models.

Erdoğan has — once more — time on his side: a staunch alliance with Trump based on mutual admiration, tepid EU responses prioritizing defense cooperation, and global democratic backsliding create permissive conditions for domestic crackdowns. He knows there will be no stumbling blocks on his path.

No ally of Turkey apparently cares that the country has the record in western alliance in terms of holding political prisoners.

According to a DEM MP, Ömer Faruk Gergerlioğlu, a politician keenly monitoring human rights breaches, there are “at least 40 thousand of them in Turkish prisons” — mayors of the CHP, Kurdish politicians such as Selahattin Demirtaş, civil society activists such as Osman Kavala or Çiğdem Mater, Gülenist publishers such as Hidayet Karaca, leftist lawyers such as Selçuk Kozağaçlı… journalists and many more.

Another Rubicon has been crossed. What unfolds next is grimly predictable: Turkey edges toward a totalitarian order where justice serves power, opposition withers under lawfare, and continuity trumps democracy.

There is only one caveat left: Turkish society, however polarised and tarnished it may be, has a far too complex DNA to be recreated in its ruler’s image.