Director of al-Hawl camp describes chaotic scenes as Kurdish guards fled and government fighters arrived.

Director of al-Hawl camp describes chaotic scenes as Kurdish guards fled and government fighters arrived. Will Christou reports from al-Hawl

THE GUARDIAN Jan.22, 2026

The children crowded the wire fence, waiting for the guard to turn his back, and made a break for it. They pumped their little legs furiously but did not make it far in the squelching mud, and were quickly chased back inside, grinning and joking to their friends in Bosnian as another guard scolded them, his rifle swinging by his side while he wagged his finger.

Their mothers, foreigners who travelled to Syria to allegedly join Islamic State (IS) and its blood-soaked caliphate, stood silently behind them. Each had their belongings packed in a bag beside them, ready to leave at a moment’s notice.

Since 2019, life inside al-Hawl, the vast detention facility in the remote Syrian desert which holds at least 24,000 suspected members of IS from 42 different countries, has stood nightmarishly still. But on Monday, time at this vast prison camp lurched back into motion, dizzyingly fast.

Camp residents watched in amazement on Monday afternoon as their Kurdish prison guards suddenly disappeared and then hours later, fighters they had never seen before showed up.

Al-Hawl was now controlled by Syria’s new government in Damascus, the fighters told residents as crowds gathered at the camp’s gates to hear what their new prison guards had to say.

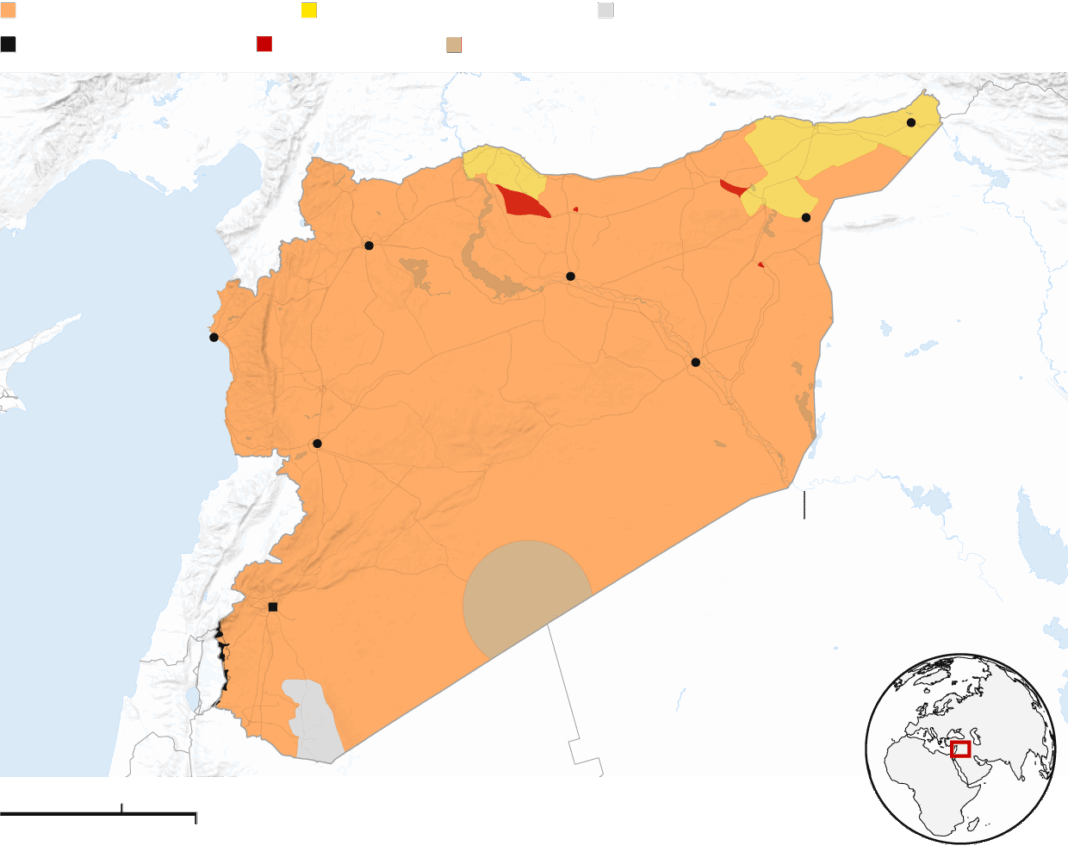

Syrian government forces took charge of the camp on Tuesday, as well as prisons housing alleged IS fighters, as they swept through north-east Syria wresting control of more than half of the territory, which for the last decade has been commanded by Kurdish forces. A fragile ceasefire between the government and separatist Kurdish forces ended on Saturday night, and Damascus appears determined to extend its control over the entire country, whether through negotiations or by force.

The world watched nervously, unsure of how well the new government, just over a year old and led by former jihadist fighters, would handle the world’s largest IS prison camp of its kind.

The Syrian government inherited a place in chaos. As the Kurds withdrew, the women and children held in the foreigners’ annexe of al-Hawl began their bid to escape, cutting the wiring of the fence surrounding their tents. In the section of the camp holding Syrians and Iraqis residents began to riot, setting a bakery alight as they protested for their release.

Syria’s interior ministry created a security cordon around the camp as people with relatives inside headed en masse to the gates, hoping to see their loved ones after years of isolation. NGOs that supplied the camp with basic goods and medical services withdrew along with the prison guards.

“We haven’t had bread in the camps for two days. Today there is no water,” said Um Mohammed, a 38-year-old camp resident originally from Idlib, north-west Syria, through the fence. Standing next to her was her 10-year-old daughter, who first entered al-Hawl when she was two years old.

“The situation is very bad and has descended into chaos. There needs to be a plan in place,” said Jihan Hanan, the director of al-Hawl camp. She left the camp along with Kurdish forces and is thinking of seeking asylum abroad, afraid for her safety amid the reports of IS members escaping from camps and prisons in the region. The market had mostly run empty, leaving residents tense and afraid. They crowded the gates of the camp, appealing to a silent row of riot gear-clad police to let them out, black smoke billowing from the burning bakery behind them.

“We welcome the Syrian government, but they should open the camp gates. We want to see our families, it’s been so long,” said Um Mohammed.

Al-Hawl was meant to be a temporary solution, a place to house people living under IS rule as Kurdish and international coalition forces defeated the extremist group’s so-called caliphate. But dealing with the approximately 75,000 people who came out of the caliphate proved difficult, and soon canvas turned to steel and the displacement camp became a semi-permanent city.

Residents languished in conditions described as inhumane by rights groups, with no access to due process and with no end in sight to their detention. For years, observers warned that the camp was a gross human rights violation, particularly since many of the camp’s residents were children, and that the international community must move to deal with the problem before it was too late. Many of the Syrian camp residents have no connection to IS, but were living in the areas they controlled and were displaced by fighting between the extremist group and the international coalition.

Syria’s civil war meant releasing Syrians and Iraqis who had tenuous links to IS was a slow process. Other countries mostly washed their hands of their citizens stuck in north-east Syria. Some, such as the UK in the case of the then teenager Shamima Begum, stripped them of their citizenship, others simply left them to their fate in the Syrian desert.

Syria’s government insists it will safeguard those inside and prevent any of the camp’s residents from escaping. It has coordinated with the International Coalition, a US-led international force that supported the Kurdish fighters in their fight against IS,on how to run the camp, and is appealing to international organisations to return and restart essential services there.

It will also probably accelerate the process of releasing Syrian and Iraqi individuals in the camp who do not have substantive evidence against them.

Women gathered at the gates after Syrian government forces took over the patrolling of the camp. Many have demanded they be released. Photograph: Khalil Ashawi/Reuters

The task ahead is daunting, particularly as the prospect of a renewed offensive against the Kurdish authorities looms. If the Damascus government succeeds in taking over further territory, it would place it in control of prisons housing hardened IS fighters and detention facilities holding minors who were brought to IS territory as children. The International Coalition said on Wednesday it would move more than 7,000 individuals with IS links to Iraq, seemingly in anticipation of Damascus advancing further into north-east Syria.

Most challenging will be dealing with the foreign residents of al-Hawl, who analysts and humanitarians say are the most extremist residents of the camps. The Kurdish authorities said foreign women worked to perpetuate IS ideology and raise their children to be the new generation of IS fighters.

“Are those cigarettes in your pocket, do you drink [alcohol]?” a young teenager asks a Syrian government soldier guarding the foreigners’ annexe. “We just got rid of the Kurds, and now you’re not even Muslims?” Another child, Ali, of Turkmen origin, said his dream was to “go to war” once he got out of the camp.

Other children were quieter, with one Azerbaijani child asking Syrian government soldiers when he could see his brother, who he said had been separated from the family and sent to another detention camp.

“I get it, if I had been stuck in this camp for years, I would also want to escape. They were oppressed here. Their countries have to take them back,” said a Syrian security force officer after chasing a group of women back into the fenced-off tent city and foiling another escape attempt. He seemed overwhelmed by the children and their frequent escape attempts, more used to battle than scolding the giggling youngsters who were running rings around him.

Al-Hawl had long been an anathema among members of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the Islamist rebel group whose former leaders now form Syria’s government. It was seen as a great injustice and featured large in the imagination among the members of the group, some of whom knew detainees inside.

Security forces around the camp expressed sympathy for the detainees, not for their alleged connection with IS, but rather their indefinite detention. Even so, rows of security officers marched around the camp, eager to show they were up to the task of securing its perimeter.

Amid the chaos, a few Turkmen children stood patiently on the edge of the foreigners’ annexe, their backpacks stuffed with their belongings. Despite a gaping hole in the fence in front of them, they did not move. “They are waiting to be smuggled out,” a security officer said, as the children stared past the fence.