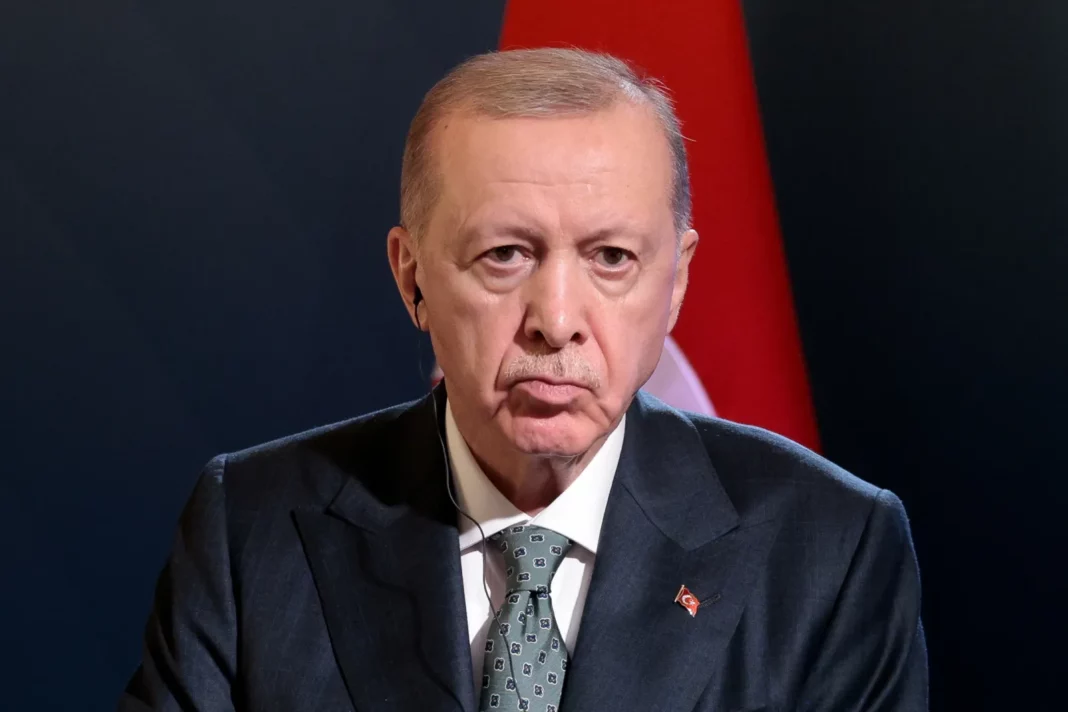

Turkey’s populist authoritarian leader, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, is now fighting for his political survival. His predicament is entirely of his own making: in the early hours of March 19, Erdogan orchestrated a raid on the home of Ekrem Imamoglu, Istanbul’s popular mayor, deploying some 200 police officers. Imamoglu, a political rival who was widely seen as a future presidential contender, was arrested and indicted on highly dubious charges, including baseless accusations of corruption and terrorism. Despite bans on public gatherings, the arrest triggered Turkey’s largest antigovernment demonstrations in more than a decade, which spread throughout the majority of the country’s provinces. Some protests in Istanbul had more than a million participants, many of whom were young.

The charismatic and competent Imamoglu may be a uniquely threatening rival. But in truth, Erdogan’s decision to arrest Imamoglu did not create this crisis. It reflected a growing weakness. Erdogan was already confronting mounting public fatigue with his presidency. His hubris and domineering leadership style have eroded the once broad enthusiasm for his rule, making him ever more desperate to constrain a now irrepressible dissatisfaction. A March 2024 Pew Research Center survey found that 55 percent of Turkish adults held an unfavorable opinion of Erdogan, and his party lost the 2024 municipal elections.

The depth, scope, and duration of the recent protests are new: the demonstrators fused their street protests with organized boycotts of pro-Erdogan businesses, online activism, and civil disobedience. Imamoglu’s arrest also brought fresh instability to Turkey’s already struggling economy. Erdogan has responded by doubling down and arresting, on a rolling basis, hundreds of Imamoglu’s associates, including colleagues, friends, former business partners, members of the Turkish business community, and family members. But these repressions now seem less like the acts of a potent authoritarian and more like the flailing of a threatened, insecure, and imperiled man. The Turkish opposition is emboldened: under new, more dynamic leadership for the first time in years, it is taking the initiative rather than ceding it to the government, organizing demonstrations in ruling party strongholds.

Although Imamoglu remains in jail, it is Erdogan who is trapped. Erdogan’s most vital imperative is to extend his presidential tenure, as he is constitutionally limited to two terms in office, and his mandate ends in 2028. But his deepening unpopularity has diminished his ability to change the constitution or force early elections. Four years from now, Erdogan will almost certainly no longer be Turkey’s president. The fact that so many young Turkish citizens dared to demonstrate against him reflects the irrevocable degradation of his popularity. As the only leader these youth have ever known, he once seemed eternal, a fact of life. But no longer: his own missteps have doomed him. Polls suggest that if elections were held in Turkey tomorrow, he would not win. Regardless of future developments, Erdogan’s legacy will likely be defined by his decision to imprison his principal opponent—and serve as an example of how even the most formidable authoritarian leaders can overstep.

TIGHTENING FIST

Imamoglu is not the first prominent political rival Erdogan has imprisoned. Selahattin Demirtas, a well-known Kurdish opposition leader, has been incarcerated since 2016 after receiving a staggering 42-year sentence for “undermining state unity,” along with an additional three years for “insulting Erdogan.” His only real “crime” was his robust support among the Kurdish populace, which posed a threat to Erdogan’s ambitions to reshape the Turkish political landscape.

But until Imamoglu arrived on the scene, Erdogan had managed to turn bouts of public opposition or the emergence of competitors into excuses to further strengthen his authority. After taking power in 2003, Erdogan promised to democratize a country whose powerful military had a long history of intervening in politics. Once the Turkish military was sidelined, however, little stood in the way of Erdogan’s ability to consolidate power. His reformist vision gradually ceded to an authoritarian construct in which Erdogan oversaw every aspect of government and society. Like many authoritarian leaders, Erdogan has used unpredictability to safeguard his ability to manipulate institutions and the state. He has supported relatively free local elections and embraced their outcomes when they are convenient—and disregarded them when they are not.

In 2013, protesters objected to a government plan to demolish Istanbul’s Gezi Park, one of the last green spaces in the city. Wary that an Arab Spring–style protest movement could arise in Turkey, Erdogan cracked down. He used (often false) allegations of participation in the protests to target both real and imaginary opponents, such as the civil society leader Osman Kavala, who was sentenced to life imprisonment for organizing and financing the demonstrations along with other coconspirators. More than a decade later, Erdogan is still wielding the Gezi Park protests as a weapon to impulsively prosecute: in January, for instance, a talent agency owner, Ayse Barim, was arrested and charged with planning to overthrow the government during the protest, although some believe that the authorities had their sights trained on her for unrelated reasons.

Erdogan’s early reformist vision has ceded to an authoritarian construct.

Then, in 2016, a failed coup by a faction within the Turkish military provided Erdogan with the opportunity to impose emergency rule, which granted him the authority to bypass the parliament and the courts and purge the government of over 125,000 civil servants, military officers, teachers, judges, and prosecutors suspected of disloyalty. Many were dismissed within a week of the attempted coup, suggesting that Erdogan had lists of enemies prepared well in advance. Riding a wave of popularity following the failed coup, Erdogan, in 2017, conducted a constitutional referendum. It transformed Turkey’s parliamentary system into a centralized presidential one, effectively eliminating the separation of powers and the rule of law and turning the parliament into a rubber stamp.

Erdogan’s government has dismissed and replaced numerous elected mayors, particularly in Kurdish-majority cities. Similarly, he has ignored decisions issued by the Constitutional Court, the sole Turkish state institution that retains some independence from him. Although he cultivates an image of omnipotence and infallibility, Erdogan is exceptionally thin-skinned. Turkish jails now overflow with politicians, journalists, academics, and citizens whose words or actions have been construed as offensive or oppositional. Individuals often languish in detention for months, awaiting trial for alleged offenses as trivial as a social media post from years past deemed insulting to the president. Between 2014 and 2020 alone, Erdogan’s government investigated approximately 160,000 Turks for insulting the president and prosecuted 35,000.

INSULT TO INJURY

But Erdogan’s apparent success at consolidating his power and undermining opposition concealed fragilities. Imamoglu’s arrest was not the first indicator of a floundering administration. Earlier this year, both the president and the board chair of the powerful Turkish Industry and Business Association criticized the Turkish state for seizing the companies and assets of people it charges criminally before they are convicted. Erdogan’s reaction was swift: he launched criminal investigations against the association leaders for, as he put it, “commenting on something they were not well informed about and, thus, spreading disinformation.”

By the time Imamoglu was arrested in March, however, he had come to pose a distinct and perhaps existential threat. Mirroring Erdogan’s own trajectory, Imamoglu rose to prominence as a capable and popular mayor of Turkey’s largest city, winning election in 2019 despite Erdogan’s attempt to repeal his victory by annulling and rerunning the vote. By focusing on efficiently delivering services, cultivating voters through a friendly style, and promoting himself as a democratic alternative to Erdogan’s aloof and increasingly authoritarian approach, Imamoglu succeeded in building an appealing national image, and he became the first political contender in years to seriously jeopardize Erdogan’s hold on power. He openly challenged Erdogan’s authoritarianism, a message that resonated with many Turkish citizens. And as a mayor with a track record, he distinguished himself within an opposition party that had long struggled to cultivate inspiring candidates or execute successful political strategies.

In 2022, Imamoglu was put on trial for insulting members of the country’s electoral council, sentenced to prison time, and banned from participating in politics. These acts were complemented by relentless, organized smear campaigns orchestrated by pro-government media. But for all of Erdogan’s efforts, Imamoglu’s influence only grew. Imamoglu appealed his conviction, resulting in a suspension pending the outcome of the petition.

Imamoglu is the first politician in years to seriously jeopardize Erdogan’s hold on power.

So Erdogan began to pull every lever he had. A day before Imamoglu’s arrest, Istanbul University, in a capricious exercise of state power, annulled his bachelor’s degree—earned 31 years earlier—on a technicality. Since Turkey’s constitution mandates that presidential candidates possess a university degree, this invalidation serves as a safeguard against any future Imamoglu candidacy. Imamoglu’s arrest preceded his party’s scheduled presidential primary by four days. Turkish political parties do not typically hold primaries, and Imamoglu was the only candidate on his party’s ballot. Unaccustomed to sharing the spotlight, Erdogan understood that Imamoglu’s selection would elevate the mayor to a position of equal standing until the next general election, which may not take place until 2028.

Erdogan wants to outlast this crisis by relying on brute force, as he did during the 2013 Gezi Park protests. But his overreach has unintentionally united and energized the Turkish opposition. Labeling protests and economic boycotts terrorism or treason or banning marches is less successful today, because the opposition now has an appealing leader in Imamoglu as well as a unifying idea: that Turkey deserves a chance at building a democracy. After years of disappointing results, the opposition has begun to reinvent itself, becoming better organized and more innovative under new leadership: as nationwide protests raged after Imamoglu’s arrest, the opposition party invited all Turkish citizens to participate in the March 23 presidential primary as a show of support. Conclusively demonstrating their discontent, over 15 million Turks waited in line for hours to cast ballots for a candidate who was sitting in jail.

Erdogan’s persecutions have made Imamoglu the opposition’s undisputed leader. From prison, Imamoglu has sustained communication with the broader Turkish public, giving the impression that Erdogan has lost control. In a recent poll run by KONDA, a Turkish polling company, 67 percent of Turkish respondents agreed that Erdogan’s reelection would be “bad” for the country, compared with 49 percent in a 2023 poll. The same poll found that more than 60 percent of Turkish citizens do not believe the accusations against Imamoglu. The longer Imamoglu remains imprisoned, the more his stature grows. It is only a matter of time before comparisons between him and figures such as Malaysia’s Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim or the Czech playwright Vaclav Havel are drawn.

DOUBLE BIND

Erdogan’s recent behavior underscores Turkey’s transformation into a typical authoritarian state in which elections serve merely to reinforce the incumbent’s grip on power. But he also appears to have lost conviction in his own standing and the unwavering support of his base. The amount of time and effort Erdogan has spent defending and rationalizing the criminal case against Imamoglu reveals his frustration and anxiety. His previous politically motivated arrests were often fueled by a desire for vengeance, but Imamoglu’s detention more clearly stems from fear. Ironically, Erdogan’s persecution of Imamoglu parallels his own experience: when he served as Istanbul’s mayor, Erdogan was also unjustly jailed—an event that elevated his national profile and secured his political future.

The Istanbul mayor’s incarceration, the arrests of other officials, and the seizure of companies’ assets have sent shock waves through Turkey’s financial markets, eroding confidence in two-year-old stabilization measures aimed at improving foreign exchange balances and reducing inflation. The stabilization plan’s success depends on attracting foreign investment, but Erdogan’s simultaneous moves to further erode the rule of law are inhibiting such investment. Two days after Imamoglu’s arrest, the Turkish lira hit record lows, and the central bank had to spend $46 billion in reserves to prevent further devaluation. Circuit breakers had to be repeatedly deployed to stop the bottom from falling out of the Turkish stock market.

Erdogan may consider himself fortunate that U.S. President Donald Trump now occupies the White House. Unlike President Joe Biden, who shunned him, Trump has effusively praised Erdogan and signaled a new U.S. policy approach; the Trump administration has remained silent on Imamoglu’s arrest. But Erdogan’s close relationship with Trump could come at a price: Erdogan routinely shored up support with his base by accusing the United States of being Turkey’s enemy and scapegoating U.S. policy for his own shortcomings. Now, he will no longer have the Americans to blame.

Polls suggest that if elections were held in Turkey tomorrow, Erdogan would not win.

A welcome event for Turkey—the start of a potential peace process with the country’s Kurdish minority—may combine with the Imamoglu crisis to break Erdogan’s hold on power. In October 2024, in an astonishing shift, Erdogan’s coalition partner—Turkey’s renowned archnationalist Devlet Bahceli—initiated a dialogue with the party representing many of Turkey’s Kurdish-majority regions in parliament and with Abdullah Ocalan, the imprisoned leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a militant group that Turkey has designated a terrorist organization. In May, this culminated in the PKK formally renouncing its 40-year armed struggle and dismantling itself. Even if Erdogan greenlighted Bahceli’s conversation with the Kurds, he did not appear enthusiastic about either the process or its results; his discourse about the opening was overly centered on security issues, maintained a punitive tone, and avoided discussing a road map.

Recognizing that the PKK’s armed struggle had reached its limits, Kurdish leaders distilled their demands into a singular, strategic request: to embark on a process of democratization. They understood that a democratic state and society governed by the rule of law with real separation of powers would be better able to handle Turkey’s challenges, including how to afford them language rights. So Erdogan faces a dilemma: the reforms and compromises necessary to initiate such a democratization process would force him to dismantle the authoritarian state structure he has meticulously constructed. His relentless efforts to keep Imamoglu and his allies in jail suggest that this is not what he wants. But if he thwarts the peace process, he risks alienating Bahceli, whose party Erdogan needs in his coalition to sustain an electoral majority and who, at 77 years old, is eager to cement his political legacy with a historic peace accord.

To remain in power, Erdogan needs either to amend the Turkish constitution or, in a more likely scenario, persuade the parliament to call for early elections, allowing him to run again. But even if he were to secure early elections, the palpable shift in public sentiment means a victory at the polls would be far from guaranteed. Increasingly isolated and surrounded by sycophants, Erdogan will likely stick to his modus operandi: responding to any challenge by reflexively wielding the state’s punitive authority. But there is a limit to the amount of bans, arrests, and the arbitrary removal of elected local officials he can pursue before Turkey is transformed into a one-party state.

The fact is that the indomitable Erdogan has run out of room to maneuver. By choosing the time and manner of his exit, he could help ease the transition to a new leader and ensure Turkey is at peace with itself. He can still shape his legacy. His personality, however, suggests that he is unlikely to embark on such a shift. If he sticks to his typical approach, there is a significant risk that the Turkish public will turn decisively against him—and that his long, eventful tenure in office will be remembered more simply as an era of autocracy.