The Jerusalem Post, December 17, 2025

Turkey was conspicuously absent on Tuesday from a US-led conference in Doha examining the possible deployment of an International Stabilization Force (ISF) to Gaza. That absence was not procedural. It was political. And from Israel’s perspective, it was both welcome and necessary.

According to multiple diplomatic sources, Jerusalem insisted on Ankara’s exclusion. Qatar and Turkey pressed Washington to reconsider, but Israel held firm. The result was an instance where Israel drew a red line, stood firmly behind it, and it was respected.

Turkey’s willingness to enter Gaza

To those outside the region who do not follow it all that closely, Turkey’s exclusion might seem a paradox. While the world is not exactly beating down the door to send troops to Gaza to demilitarize Hamas as part of the second stage of the Trump peace plan, Ankara has said it is ready to send some troops immediately.

So at a time when Washington is struggling to find countries prepared to operate in contested areas of the Strip, Turkey’s willingness might seem like an asset. But it is not. Far from it.

The stated purpose of the ISF is to help disarm Hamas, maintain security during a transition to Palestinian technocratic governance, and prevent Gaza from again becoming a launchpad for attacks on Israel.

Any force that cannot advance those objectives would be worse than useless because it would make it more difficult for Israel to do so if it felt it had no other choice. Just look at the UNIFIL example, where not only did its troops fail to keep Hezbollah from building up in southern Lebanon, but they also made it more difficult – diplomatically and operationally – for the IDF to operate there when necessary.

Furthermore, allowing Turkish troops into Gaza would not only undermine the mission – it would invert it.

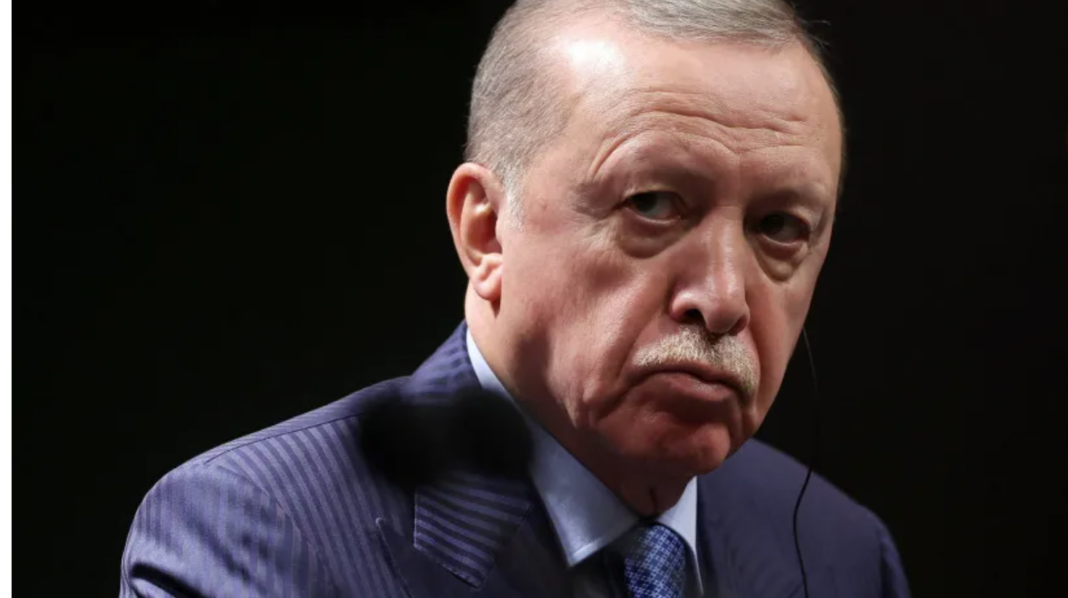

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s deep hostility toward Israel did not begin on October 7. It is a core ideological position that has defined his leadership since he took office as prime minister in 2003. Over two decades, through Operation Cast Lead, the Mavi Marmara incident, repeated Gaza wars, and most intensely since October 2023, Erdogan has portrayed Israel not as a rival or adversary, but as a moral and political enemy.

In March this year, on the occasion of Eid al-Fitr, he publicly prayed for Israel’s destruction. “May Allah make Zionist Israel destroyed and devastated,” he beseeched. That was not rhetorical excess in the heat of war; it was an expression of long-time enmity toward the Jewish state on display throughout his long years in power.

What distinguishes Erdogan from other regional critics of Israel is not only the rhetoric but also the translation of words into policy.Since October 7, Turkey has formally cut trade ties with Israel, cut diplomatic relations, closed its airspace to Israeli planes, and joined South Africa’s genocide case against Israel at the International Court of Justice. These are more than just symbolic gestures; they are hostile economic, diplomatic, and legal actions meant to cause Israel maximum damage.

Even more telling is Turkey’s behavior inside multilateral security frameworks. Over the past year, Ankara has repeatedly used its veto power within NATO to block Israeli cooperation with the alliance. Joint exercises, meetings, and emergency preparedness initiatives have all been frozen at Turkey’s insistence.

That precedent matters. A country that uses its position inside NATO to constrain Israel cannot plausibly be expected to act as a neutral security guarantor in Gaza. If Turkey is willing to sabotage Israel’s standing with NATO, there is no reason to believe it would behave differently on the ground in Khan Yunis or Jabalya.

Then there is the Hamas problem – the central, unbridgeable contradiction precluding any possibility of Turkish troops in Gaza. Turkey does not merely tolerate Hamas. It hosts it, supports it, and whitewashes its crimes.

Senior Hamas figures have operated openly from Istanbul for years. Some have received Turkish citizenship. Turkish intelligence maintains channels with Hamas leadership. Ankara has never designated Hamas a terrorist organization, and Erdogan has repeatedly described it as a “liberation movement” and “freedom fighters.”

This is not semantic quibbling; this is how Erdogan sees Hamas within the Muslim Brotherhood “family” to which he is ideologically aligned.

A country that provides sanctuary to Hamas leaders, maintains institutional ties to the organization, and views them as “freedom fighters” cannot credibly be tasked with disarming it. Turkish officials have said as much themselves.

Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan argued recently that the problem is not Hamas but “occupation,” and that disarming Hamas without first transforming Israel’s policy is misguided.

“What we are saying is this: the issue should not begin with disarming Hamas, but with establishing a mechanism that ends the occupation and reduces and eliminates oppression. This logic needs to be clearly explained,” he said.

Fidan’s worldview is fundamentally incompatible with the mission Washington says the ISF is meant to fulfill. Turkey is willing – indeed, eager – to deploy troops, but not to do the job Israel needs done or the one Washington has laid out.

There is also a military dimension that cannot be ignored. Erdogan has in the past threatened direct military intervention against Israel, explicitly referencing Turkey’s actions in Libya and Nagorno-Karabakh.

“We must be very strong so that Israel can’t do these ridiculous things to Palestine. Just like we entered Karabakh, just like we entered Libya, we might do [something] similar to them,” he said during a meeting of his AK Party in 2024. “There is no reason why we cannot do this … We must be strong so that we can take these steps.”

Analysts may debate whether such threats are bluster, but their existence alone disqualifies Turkey from any role in Gaza. A state whose leader publicly talks about a military confrontation with Israel cannot be embedded inside the coastal strip.

Against this backdrop, Israel’s position is not obstinate. It is reasonable. It is welcome that the US administration, even though President Donald Trump has a good relationship with Erdogan, seems to see it this way as well, as illustrated by the decision not to invite Turkey to the Doha meeting.

Allowing Turkish troops into Gaza would mean placing an actor with ideological sympathy for Hamas, operational ties to its leadership, and a record of punishing Israel through international institutions into the heart of the mission. That is not stabilization but rather sabotage – a Trojan horse brought in under an international flag.

The alternative to the ISF – Israel having to dismantle Hamas itself rather than outsourcing the task to a compromised international force – is not without cost. It would entail prolonged Israeli military presence, international pressure, and loss of life. But the rationale is at least understandable. Delegating the mission to a power hostile to Israel’s objectives is not.

Turkey’s exclusion from Doha also sends a message to Ankara: words and actions have consequences. A force tasked with dismantling Hamas cannot include a state that houses, finances, and ideologically supports Hamas. A stabilization mission cannot be anchored by a country led by a man who sees Israel – rather than the terrorist organization that carried out the atrocities of October 7 – as the regional problem that needs to be dismantled.