Reporting Hugo Dixon in Reuters on February 27, 2023. Investors have shunned Turkey in recent years as President Tayyip Erdogan let inflation rip. The country’s relations with the West have deteriorated as he cosied up to Russia’s Vladimir Putin. He has also done too little to rein in carbon emissions. An opposition victory in upcoming elections, which is more likely after this month’s deadly earthquake, could change all that.

Erdogan may yet retain power in presidential and parliamentary elections expected to be held in June. But the earthquake which struck southeast Turkey earlier this month, killing nearly 44,000 according to official figures, has damaged him. So consider the scenario where he loses.

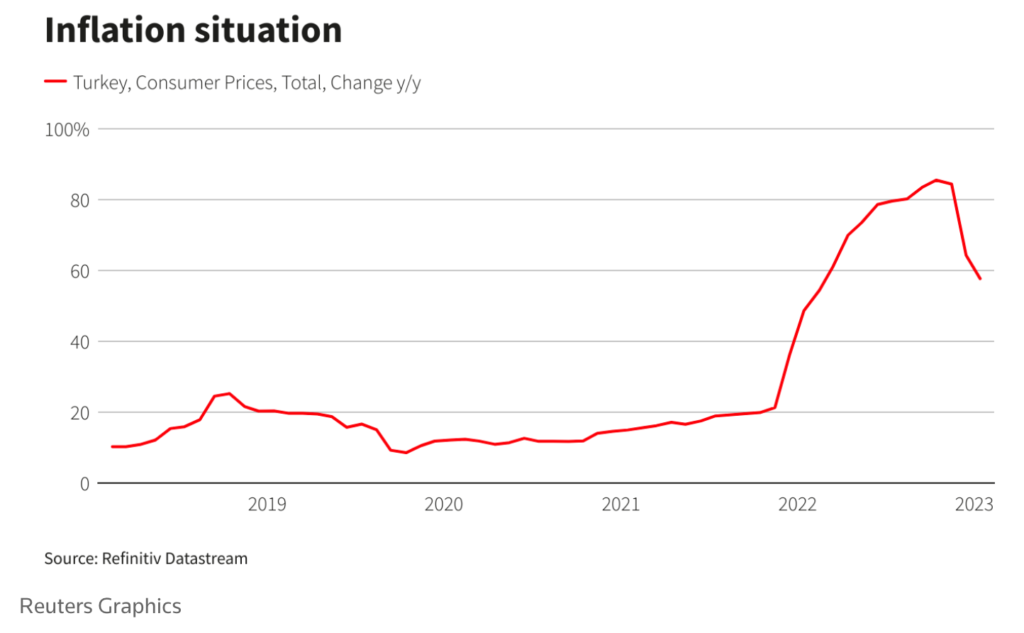

The six-party coalition challenging the ruling AK Party plans to stamp out inflation, which official figures put at 58%. It is committed to restoring democratic norms and the rule of law, which Erdogan’s 20-year rule has undermined. It would also make clear that Turkey is a loyal member of the NATO alliance. The current president’s decision to block Swedish and Finnish membership of the transatlantic defence pact has thrown that into doubt.

These policies would lead to an influx of Western investment and could pave the way for a new trade and climate deal between Turkey and the European Union.

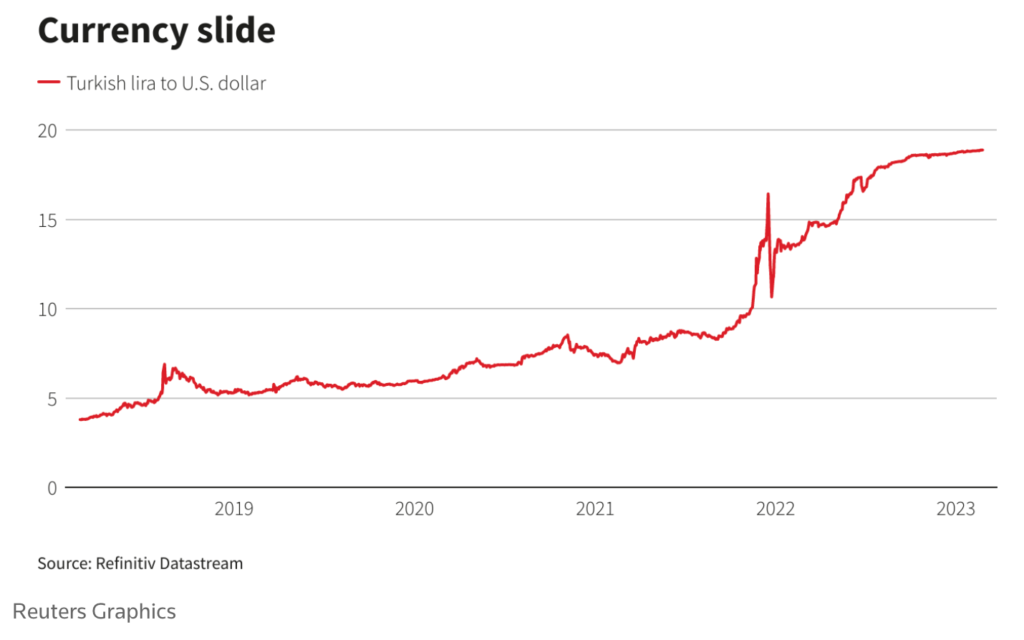

The opposition’s proposed economic reforms would bring short-term pain. But Erdogan’s unorthodox policies are storing up a much worse financial crisis. Last week Turkey’s central bank, which is under the president’s thumb, cut interest rates to 8.5%, which means the real cost of borrowing is massively negative. The monetary authority has also been selling foreign exchange to prop up the lira , despite having few international reserves.

EYE-POPPING INTEREST RATES

Despite the opposition’s pledge to restore the central bank’s independence, it will be tough to crush inflation. After all, if the lira slides, inflation will initially rise. What’s more, Turkey may need eye-popping interest rates to control prices. That could trigger a recession, undermining a new government’s popularity. International investors may sit on the sidelines until they are sure it has the stomach to swallow the medicine required.

Erdogan has also created a banking mess. His government forced lenders to buy low-yielding government bonds. As interest rates rise, those institutions will face big losses. The government also promised to protect lira deposits in the event of depreciation. So a new administration may have to recapitalise the country’s banks and fork out cash to depositors. With gross government debt at only 38% of national income, however, Turkey could afford a hit.

A new government may also discover other “skeletons”, says Tim Ash, a strategist at BlueBay Asset Management. For example, there is little transparency over Erdogan’s deals with Putin, including whether Russia was one of the “friendly” countries that lent Turkey money to boost its foreign exchange reserves.

That said, if Turkey faces a financial crisis, it could turn to the International Monetary Fund for a hard-currency loan. The six-party coalition should probably do this pre-emptively to gain extra economic credibility, though it seems unlikely to do so.

TESTS OF LOYALTY

A new government would be well placed to forge closer relationships with both the EU and the United States. Its commitment to democracy would certainly ease that path. So would its expected approval of Sweden’s and Finland’s NATO memberships.

America and the EU would also want the six-party coalition to crack down on any companies that help Russia import military-useful equipment. A top U.S. official has already warned that such firms could face sanctions.

While Erdogan’s government says it will take action on sanctions-busting if it gets evidence of violations, a new government would probably cooperate more willingly. However, it wouldn’t cut off other exports to Russia. These have soared following Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, as some Western goods now go to Russia via Turkey.

Nor would the six-party coalition stop buying Russian hydrocarbons. Turkey depends on imports for 99% of its gas and 93% of its oil. It is also profiting from buying discounted Russian oil, refining it and selling it to other countries.

CUSTOMS AND CLIMATE

Turkey will not join the EU, its largest trade partner, any time soon. The main prize, rather, is to modernise its customs union with the bloc. Member states refused to push this forward because they were unhappy with Erdogan’s growing autocracy, but should be willing to start again with a new government.

The old plan was to enhance the customs union by including public procurement as well as trade in services and agriculture. It would now make sense to add climate policy and trade in digital services too, says Sinan Ülgen, the director of Edam, a Turkish think tank. Nathalie Tocci, a former special adviser to two EU foreign policy supremos, shares this view.

Ülgen says the opposition would probably introduce carbon pricing similar to that being introduced in the EU. Turkey could then avoid the carbon tariffs the EU is planning to impose on imports. An expanded customs deal would attract foreign investment even before it took effect.

The United States might also increase trade with Turkey if its geopolitical orientation was clearer. This would dovetail with America’s “friendshoring” initiative, which aims to build up supply chains in friendly countries as a counterweight to China.

A big climate deal wasn’t on the cards with Erdogan, who only ratified the Paris Agreement on climate change two years ago. But the Group of Seven large industrial nations should offer a new government one of its “just energy transition partnerships”. This would mobilise many billions of dollars of private and public investment to fast-track Turkey’s decarbonisation.

The EU and America are understandably saying nothing now about the opportunities of a post-Erdogan era. The president has clung to power before and may hang on again. But it is not too early to think about how to bring Turkey in from the cold if he loses.