ABSTRACT

It would be an understatement to say that Şerif Mardin’s center-periphery thesis (CPT) has been influential on contemporary understandings of Turkey. This essay reflects on the impact of the CPT, considers the challenges from both critics and a changing empirical reality, and discusses whether it still has something to offer us today. It argues that some of the criticisms levied at Mardin’s thesis are based on a misunderstanding of the role of simplification in social science, while others point to important shortcomings of the theory without presenting an alternative framework. However, the article suggests that the anomalies in the CPT have by now amassed to the point that it no longer serves as a meaningful approximation of key dynamics in Turkish politics, primarily because it fails to capture the importance of the Kurdish issue and the consolidation of the ruling AKP at the center.

Institute for Turkish Studies, Department of Economic History and International Relations, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden.

Access to the article in Taylor & Francis Online

Introduction

Standing at the cusp of the centenary of the Turkish Republic and looking back, it is hard not to be struck by how many observers have portrayed Turkish politics and society as characterized by a deep divide. The single most influential depiction in this genre is arguably Şerif Mardin’s 1973 article, ‘Center-periphery relations: A key to Turkish politics?’1 It would be an understatement to say that Mardin’s center-periphery thesis (henceforth CPT) has been highly influential on contemporary understandings of Turkey. In both scholarship and popular depictions of Turkey that followed the publication of his seminal article, the notion of a division between the secular state center and conservative-religious periphery has played a large and growing role.

His thesis has not been without its detractors, however, and Turkey itself has undergone a significant transformation from the time when Mardin drafted his thesis, raising questions about whether it still is applicable. In this essay, I reflect on the impact of the center-periphery thesis, consider the challenges from both critics and a changing empirical reality, and discuss whether it still has something to offer us today.

This article begins by exploring the impact of Mardin’s article a little further before describing the main argument. After having clarified what Mardin did (and did not) say, it considers some of the most relevant rejoinders, and concludes by assessing its continued relevance.

The impact of the center-periphery thesis

Why devote a whole essay in this Special Issue of Turkish Studies to one article published half a century ago? The answer is simple. In the words of one of its critics, Mardin’s article is ‘now indisputably one of the foundational works on Turkish politics, and arguably the most influential single work.’2 Another critic describes the model as has having exercised a ‘decades-long hegemony’ over mainstream scholarship.3 A citation search on Google Scholar reveals how often it has been referenced by other scholars in the field (Figure 1). It lived its first decades in relative obscurity, but in the early years of the new millennium the number of citations began growing rapidly until reaching nearly one hundred citations per year in 2017, and it has remained relatively steady at that number since then.

A look at the caliber of authors citing Mardin’s article also suggests the impact it has had. They include a veritable who’s who of social science scholarship on Turkey: Yeşim Arat, Pınar Bilgin, Sinan Ciddi, Ali Çarkoglu, Ioannis Grigoriadis, Haldun Gülalp, Iştar Gözaydin, William Hale, Metin Heper, Ayşe Kadioglu, Ersin Kalaycıoglu, Alper Kaliber, Reşat Kasaba, Ayhan Kaya, Ziya Öniş, Ergün Özbudun, Sabri Sayarı, Murat Somer, Hakan Yavuz, and many more.4

The basic thrust of Mardin’s analysis has also permeated writings far beyond academia. His depiction of a polarized country wrestling with a single major division and struggle between a modernizing, secular center and a conservative, religious periphery is one that readers of popular and journalistic accounts of today’s Turkey will no doubt recognize as well. Samuel Huntington’s seminal (if oft-criticized) ‘Clash of Civilizations’5 failed to cite Mardin, but the depiction of Turkey as a country ‘torn’ between Western and Islamic civilizations contained more than an echo of the CPT. In other words, the CPT deserves serious consideration simply because of how influential it has been, in academia and beyond. This is so whether one agrees with it or not.

From a sympathetic point of view, one could point out that it would arguably not have wielded such influence among astute observers of Turkey unless it captured something important about the country. Hence, one reason to pay it attention is because the argument in some ways remains persuasive. To many, it seemed that the rise of the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AKP) vindicated Mardin’s thesis about a society polarized between Islamists and secularists. One could debate whether the wide diffusion of this binary account is a measure of the extraordinary success of Mardin’s article or simply a function of an empirical reality that Mardin was just one of many scholars to describe. However, even if the latter were to hold true, it remains a fact that Mardin was the first to convincingly describe and conceptualize what he and many others after him have seen.

At the same time, the CPT has also been subject to much criticism. The large number of citations, especially in recent years, include many publications that mention it only to point out its flaws. Hence, a quite different reason to consider the CPT seriously is that if the critics are right in that it misconstrues and/or overly simplifies key Turkish dynamics, its popularity means that it has done a lot of damage to both academic and mainstream understandings of developments in Turkey. It is therefore important to address any such shortcomings to minimize the ‘damage’. However, before we engage the arguments of the critics, let us set briefly set the context and then nail down the broad brushstrokes of Mardin’s argument.

The context

Şerif Mardin was born in Istanbul in 1927 to a family that was among the Ottoman eşraf (prominent citizens).6 His father, Şemsettin Mardin, was a diplomat with postings in Lebanon and Syria. He was born in Egypt, which is also where he met Şerif’s mother. Reya, the daughter of prominent Ottoman publicist Ahmet Cevdet Oran. Mardin started high school at Galatasaray Lisesi in Istanbul but completed it in the USA, and followed up with three academic degrees at two prominent American universities: Johns Hopkins (an M.A. in International Relations in 1950) and Stanford (B.A. in 1948 and then a Ph.D. in Political Science in 1958). Mardin’s doctoral thesis was published in 1962 under the title The Genesis of Young Ottoman Thought by Princeton University Press. He returned to Turkey to take up a position at Ankara University, and between 1973 and 1991 (after research stints at Princeton and Harvard), he taught at Bosphorus University.

Mardin had returned to Turkey only one year after the military coup that he described as the ‘Revolution of 1960’ aimed at ‘the preservation of the static order.’7 When he wrote the article under examination here, Turkey was at the tail end of another military interregnum that lasted from 1971, when the government of Süleyman Demirel had resigned in response to an ultimatum issued by the military, to 1973, when the country returned to multiparty politics. In Mardin’s words, the 1971 intervention was perceived by ‘the periphery’ as an attempt to ‘return to the rigidity of the old order.’8 Turkey was by then a modernizing country that was undergoing rapid urbanization and industrialization. Atatürk’s reforms had been transformational, but there had also been resistance from religious and conservative groups since at least the 1950s, and the unilateral American decision to remove nuclear missiles from Turkish soil during the Cuban missile crisis in 1962 had generated pushback against Turkish political leaders who had thrown all in with NATO and the Western camp.

He was thus writing at a time in which tensions between the older Republican elite and new populist parties that claimed to represent peripheral groups had been at the forefront for nearly two decades and had generated two military interventions into politics. Mardin was examining a dominant division of his time. He had also (unsuccessfully) flirted with politics himself, in the short-lived liberal Hürriyet Partisi formed in 1955 by MPs expelled from the ruling Demokrat Partisi (DP) when they objected to the increasingly repressive policies of the DP government. Mardin was party secretary between 1956 and 1957. Like few others, he could combine an outstanding American training in modern comparative political science, sociology, and history with his own and his family’s tangible experience of being at the center of both Ottoman and early Republican society. This context informed his ground-breaking 1973 article, to which I shall now turn.

Mardin’s main argument

Mardin’s article, published in Daedalus, starts with the identification and analysis of a central dynamic in late Ottoman society, and then explores what happened to it during the early Republican period, arguing that the transition from empire to nation-state did little to erase this central tendency. Mardin himself summarized his main argument succinctly: ‘Until recently, the confrontation between center and periphery was the most important social cleavage underlying Turkish politics and one that seemed to have survived more than a century of modernization.’9

The deep binary division in late Ottoman society that Mardin described had many causes. It was a legacy of a ‘basic cleavage between nomad and sedentary population[s].’10 It was also a function of the nature of the imperial state and its weak integrative capabilities. This weakness assured ‘local notables’ an important role as they acted as intermediaries between the imperial center and peripheral populations. Consequently, the imperial elite harbored deep ‘suspicion … towards … powerful families in the provinces.’11

According to Mardin, the division between the imperial center and the periphery was reinforced by a range of cultural, legal, and economic factors. Imperial officials were long recruited from non-Muslim groups, and held special legal and economic status. The state and its officials claimed ‘cultural preeminence’. In contrast to ‘the heterogeneity of the periphery, the ruling class was singularly compact; this was, above all, a cultural phenomenon’ where it was influenced by Persian and Arabic cultures and languages, which were foreign to the lower classes.12

In contrast to the cultural homogeneity of the imperial center, the attitude of those throughout the empire who ‘opposed the state’s incursions into the economic and social life of the periphery’ was infused with ‘localism, particularism and heterodoxy.’13 So-called ‘primordial groups’ were important as sources of identification in the periphery. Between these peripheral groups and the imperial center, then, there was constant tension, according to Mardin.

This central tension was managed through a number of integrative mechanisms during the heyday of the Ottoman Empire, but as the empire began its decline, tensions flared. There were a number of revolts by elements in the periphery, often in reaction to attempts by imperial officials to introduce modernizing reforms. Mardin claims that this – certain interest groups mobilizing the masses in reaction to Westernizing reforms – was to become a pattern often repeated.14

During the nineteenth century, the heterogeneity of the periphery was diminished, as an ‘Islamic, unifying dimension’ was added to the ‘peripheral code’.15 The ‘provincial world as a whole, including both upper and lower classes, was now increasingly united by an Islamic opposition to secularism.’16 During modernization, the periphery also came to be increasingly identified with ‘primordial’ groups and as the locus of a ‘counter-official culture’.17

According to Mardin, this societal division was not bridged by the top-down modernizing state- and nation-building reforms of the Republican People’s Party (Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi, CHP) during the Republican era. Much like imperial officials before them, the party ‘was unable to establish contact with the rural masses.’ The peasants ‘still depended on the notables for credit, social assistance, and, in some regions of Turkey, protection.’18

Capitalizing on the failures of the CHP and officials of the state to connect with the people of the periphery, the ‘electoral campaigns of the Democrat Party relegitimized Islam and traditional rural values’ and employed client politics at new levels.19 The DP was created by former CHP members in 1946, and one might reasonably claim, Mardin argues, that ‘the Republican People’s Party represented the ‘bureaucratic’ center, whereas the Democrat Party represented the ‘democratic’ periphery’, and was the real ‘party of movement’.20 As I noted above, to Mardin, the military coup of 1960 as well as the intervention which had occurred only two years before the publication of the article, were attempts by actors representing the center to preserve or restore the ‘rigidity of the old order’ in opposition to ‘those who wanted change.’21

One final aspect of Mardin’s paper that is perhaps not often enough acknowledged is that he offers a number of important caveats to his thesis. Towards the end of the article, he admits that ‘the picture is, in fact, more complex’ and goes on to identify organized labor and the Kurdish movement as constituting cleavages that cut across the main division that his article describes.22 He acknowledges ‘new cleavages and differentiation within the periphery’ and defections from the bureaucratic center to parties representing the periphery. Nevertheless, having noted these countervailing trends and forces, he concludes that ‘these are future aspects of Turkish politics, and center-periphery polarity is still one of its extremely important structural components.’23

Key criticisms

This short essay does not claim to provide a complete overview of all the criticisms leveled at Mardin’s thesis. Rather, it will highlight and discuss some of the more interesting ones, at least from my perspective. One way of looking at the critiques is to view them as falling on a spectrum from more normative/ideological to more empirical. At the one end of this spectrum, we would find critics emphasizing the normatively problematic origins of the theory or its problematic policy consequences. On the other end, there are critics whose main concern is that the model is inaccurate or fails to explain the kinds of phenomena that it should. This spectrum is a simplification as even those arguments that I will describe as more normative are based on empirical observations. I am here only concerned with scholarly critiques, so none of the rejoinders that I describe here are purely political or normative in nature.

Nevertheless, I will begin by considering two critiques that focus, respectively on the problematic origins of the theory and its problematic consequences. I will then consider critiques that emphasize what they see as the overly simplistic binary nature of the model and conclude by looking at one critique that argues that the model fails to adequately explain voting behavior.

Normative critiques (Is it good?)

One of the most thorough recent discussions and critiques of the CPT and its proponents can be found in a doctoral thesis presented in 2020 at Helsinki University by Halil Gürhanli.24 Gürhanli traces the origin of Mardin’s model to American and European modernization theory:

Tracing the roots of this highly influential model in the elitist conception of society originally theorized by Edward Shils (1956; 1961; 1975), the argument here is that a set of deeply modernist, elitist, and anti-populist assumptions underlying this model were also imported—inadvertently or not—into Turkish political science literature.25

Gürhanli is interested in the phenomenon of populism in Turkey and argues that the elitist assumptions of modernization theory imported into Turkish social science via Mardin’s model came to distort understandings of Turkish populism for decades. Hence, much Turkish scholarship came to focus on DP clientelism as an indication that Turkish politics was stuck in conservative and religious particularism: the politics of nepotism and loyalty networks as opposed to the kind of politics allegedly practiced in developed countries, where parties compete on who can best serve the general interest. In other words, the CPT frame presented Turkish politics and society as insufficiently modern in comparison to its Western counterparts.

A similar critique is presented by Güngem and Ertem,26 who decry Mardin’s approach as Orientalist because he takes a European developmental path as the norm and thereby presents Ottoman society as a ‘deviant’ case. According to Güngem and Ertem, this perspective is also present in works of other scholars, such as Metin Heper.27 Gürhanli agrees and adds that it is also visible in many Marxist accounts of Turkish populism.

It appears to me difficult to deny the influences of key thinkers in the modernization paradigm on Mardin’s own thought. Indeed, his 1973 article cited studies of the development of European states, including Lipset and Rokkan’s influential cleavage theory piece published six years earlier. In it, Lipset and Rokkan identify the center-periphery axis as one of two key conflict dimensions in modernizing countries. What they call the ‘National Revolution’ generated tensions that turned into fundamental societal cleavages, and they describe it in terms that clearly influenced Mardin:

the conflict between the central nation-building culture and the increasing resistance of the ethnically, linguistically, or religiously distinct subject populations in the provinces and the peripheries.28

Mardin’s argument regarding the role of the center-periphery cleavage in the Ottoman Empire and early Turkish Republic is almost a direct restatement and application of Lipset and Rokkan’s argument in this passage. His work also builds on a tradition of Turkish historical scholarship that was partially embedded in the modernist tradition, like Halil Inalcik, whom he cites extensively. Inalcik’s 1964 contribution to Ward and Rustow’s Political Modernization in Japan and Turkey laid out similar themes when examining tensions between early twentieth century Westernizing reformers in the Ottoman Empire and the heterogenous collection of often conservative âyans, local notables who resisted the reforms.29 Like Inalcik, Mardin saw important continuities despite the fall of the Empire and establishment of the Republic. In short, Mardin was working within or at least explicitly drawing on a Western tradition of history, political sociology and comparative politics from which the oft-criticized modernization theory emerged.

Nevertheless, it does not necessarily follow that his work on the Ottoman Empire and Turkey suffers from the Eurocentrism that plagued some of the work that falls more directly within the category of modernization theory. Certainly, other critics of the CPT, like Haldun Gülalp and Onur Bakiner, see this differently. Gülalp describes the CPT as ‘[r]ightly critical of modernization theory, which characterizes Islamism as a backward ideology that is doomed to extinction.’30 In his critical appraisal of CPT, Bakiner grants that the approach ‘has long been criticized for promoting Ottoman-Turkish exceptionalism and a peculiar form of Orientalism’, but disagrees with this assessment.31 To Bakiner, Mardin’s ‘article explains how a set of initial political-institutional conditions set off divergent developmental paths without essentializing the West or the East.’ Instead, he believes that it should be seen as part of Mardin’s ‘broader project of incorporating religious institutions and practices as important elements of description and explanation in studies of modernization, rather than pre-modern leftovers.’32 Hence, whether the CPT has imported problematic Eurocentric assumptions from modernization theory is a contested matter.

Another ‘normative’ critique focuses on its consequences rather than origins, specifically the role it has played in the political transformation of Turkey under the rule of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s AKP. As noted above, part of the appeal of the model in recent years was that it offered a ready framework with which to interpret the spectacular rise and success of the AKP. In this interpretation, the AKP and its predecessor, the Islamist Welfare Party, as the distant successors to the DP, heralded the rise of the periphery. To paraphrase Mardin’s account of the DP, it was the AKP that had become the ‘real party of change’, against the CHP and traditional military and bureaucratic elites. As Gürhanli notes, even Erdoğan himself (or at least his speech writers) explicitly understood his party in these terms. In a speech to the first party congress in 2003, he spoke of the old division between a political center and a periphery that he dubbed the real ‘societal center’: ‘The real achievement of the AKP is its novel understanding of politics that has done away with the disconnect between the societal and political centres, rendering them identical instead.’33

Onur Bakiner identifies the same phenomenon and suggests that the rise in citations from the turn of the millennium that we observed above (Figure 1) ‘appears to reflect the AKP’s rise to power, as most scholars began to discover traces of the periphery in the AKP’s rhetoric.’34 Writing at a time when the authoritarian tendencies of the AKP had become more apparent, Bakiner criticizes the early uses of the CPT to not just describe a conservative-liberal alliance in the early 2000s but also to present it as a revolutionary-democratic force for change. The framework was appealing to both Islamist intellectuals, for whom it ‘offered the promise of self-identification with the oppressed [mazlum]’, and liberals,35 for whom it ‘presented the opportunity to build alliances with other sectors in opposition to Kemalism.‘36

Ergün Özbudun, writing in 2006, illustrates the hope that many liberal observers in Turkey placed in the AKP early on:

[T]he transformation of Turkish political Islam […] into a moderate conservative democratic party […] can be seen as a significant step toward bridging the age-old deep cleavage between secularists and Islamists, thus contributing to the consolidation of democracy in Turkey.37

A democratic and reformist AKP, with its peripheral party base, held the potential to overcome the old center-periphery divide that had caused so much damage to popular democracy in Turkey. In view of the party’s subsequent authoritarian turn, it is easy to be critical of this view. According to Bakiner, liberal intellectuals were naïve to accept the reformed Islamists’ take even at the time. He notes that it had long been clear that opposition to Kemalism had often ‘taken the form of right-wing authoritarianism rather than pluralist democracy.’38

In many ways, these scholarly differences over academic accounts of the progressive potential of a liberal-conservative alliance during the ‘Golden Years’ of AKP reforms (a term I borrow from Öniş and Yilmaz39) are simply reflections of an existing dispute in Turkish politics. There have been fierce arguments between some liberals (in the Turkish sense) and Kurdish activists on one hand, who both saw the AKP in the early 2000s as the only force that could break the power of the bureaucratic center and the ‘deep state’ and, on the other hand, secular Kemalists and other skeptics who always suspected the AKP of harboring a hidden agenda, which was both Islamist and undemocratic in nature. These disagreements came to the fore in the 2010 referendum on a constitutional reform package that contained both democratizing measures and proposals that would break old Kemalist elite’s grip over the judiciary. The skeptics saw the proposed legal reforms as designed to provide the executive and thus the AKP with the instruments to secure control over the judiciary following a bruising legal battle that nearly saw the party closed in 2008.40 A group of liberals disagreed, proclaiming famously that they would support the proposed amendments even though they were insufficient (Yetmez ama evet!).41 The liberals argued that the changes were needed for ‘the liquidation of the authoritarian, statist, and tutelary features of the 1982 Constitution’ and therefore were a step in the right direction.42

In one sense, the CPT became a victim of its own success. The success and political appropriation of the CPT meant that a theory meant to be descriptive arguably came to exert influence on the matter it purported to explain, in what Gürhanli (citing Habermas) describes as a double hermeneutic. To those critical of arguments by Turkish-style liberals along the lines of the ‘Yetmez ama evet!’ campaign, this means that Mardin’s theory could be criticized from a normative standpoint. It served to legitimize and mobilize liberal support for Erdoğan’s quest to defeat his political opponents in the establishment, thus enabling him to consolidate power and establish autocratic rule.

Empirical critiques (Is it right?)

Apart from these critiques of the normative dimensions of the theory, there are a number of objections to the CPT that focus primarily on its failures to accurately describe or explain empirical facts. A common theme in this line of critique is that the theory is overly simplistic, and that the binary nature of the approach and its focus on a single conflict dimension means that it fails to capture significant societal phenomena. For example, Bakiner argues that the thesis overstates the homogeneity of the center, pointing to, among other things, instances of disunity among left- and right-wing jurists and distrust between the judiciary and the military, two key actors in the so-called ‘deep state’ that formed a key bloc in the supposed center.43

One of the more convincing rejoinders to Mardin’s thesis comes from F. Michael Wuthrich,44 who focuses on voting patterns that do not seem to conform with the notion of a key societal and political divide between center and periphery. Looking at voting in the early multiparty period, he argues that the CPT does not adequately describe voting patterns, especially not in the first multiparty elections of 1950 and 1954. According to Wuthrich, the DP could not adequately be described as a ‘peripheral’ party either by reference to the background of the party’s candidates or its political platform. Moreover, he argues that there was little of the stability over time in voting preferences that one would expect if Mardin’s portrayal of ‘the most important societal cleavage underlying Turkish politics’ had explanatory power.

Neither were there geographical voting patterns that a geographic interpretation of the center-periphery framework would predict. Wuthrich instead shows the CHP as having particularly strong performance in what is usually described as the ‘peripheral’ regions of southeastern and eastern Turkey, while it did poorly in Marmara and the Aegean regions during the 1950s. The supposed ‘party of the periphery’ –the DP—instead performed well in the more developed western regions and poorly in the periphery. That apparent poor fit with voting data prompts Wuthrich to ask why Mardin’s article has become so popular. His answer is that it appeared to fit the situation in the early 2000s better than the period Mardin purported to explain, at least on a first glance:

By the time we reach the three general elections held between 1999 and 2007, […] the map appears to be a near spatial reversal of the 1950s portrait […]. This might be one reason that the notion of a center-periphery political cleavage has successfully been maintained into the twenty-first century. The idea of a culturally Western and modernized ‘center,’ represented by parties often referred to as the ‘center-left,’ combating the traditionalist, Islamist populace of the central and eastern Anatolian regions seemed to fit the superficial portrait of more recent voting behavior.45

On closer look, however, Wuthrich is critical of such an extrapolation of the CPT thesis into a modern-day secular-religious cleavage as well, because that does not fit the data either. Modern studies of geographical voting patterns identify at least three distinct regions: western/coastal, central Anatolia, and the southeastern regions, which are not neatly captured by any binary framework. I will return to the last point below.

This brings us to the question of the utility of Mardin’s framework for understanding Turkish politics in general, and today in particular. In light of both the above discussion of key criticism of the framework and our knowledge of recent developments, are we ready to discard the center-periphery thesis once and for all, or does it still provide important insights?

Discussion: assessing the utility of the framework

Still the best thing out there … ?

I must confess to being of two minds when it comes to Mardin’s classical thesis. On one hand, it is both overly simplistic and hard to fully understand, and it appears to fail to explain some key outcomes, as we have seen. On the other hand, it is difficult to disregard the sentiment that it captures something real and important about how many Turks themselves perceive of Turkish society and politics. Since we have covered key criticisms above, I will begin with some observations that point in favor of the continued relevance of the thesis, followed by my own main objections and summary assessment.

My first defense of the CPT framework is in response to criticism of the framework on the basis that it is a simplification. Simplicity in itself is not a weakness of a social scientific theory. In fact, parsimony and simplicity are traditionally identified as having intrinsic value in science, such that of two otherwise equally convincing theories, the simpler one is to be preferred.46 This principle was first articulated by the medieval Scholastic philosopher William of Ockham: pluralitas non est ponenda sine necessitate (‘plurality should not be posited without necessity’).47 His admonition to not complicate things unnecessarily has become known as Occam’s razor, and on some interpretations it places value not just on parsimony but also elegance.48

In contrast, much of contemporary critical social science is aimed at showing how established theories are flawed in the sense of obscuring complexity. The point of such deconstruction is less to try to better capture an objective reality than to show how existing attempts to do so (theories and scientific discourses) distort and hide power struggles, dominance, and resistance. Any theory purporting to describe or explain societal phenomena must simplify, and it is therefore useful to point to the costs of doing so.

However, a critical deconstruction that reveals costs of simplification in the sense of the weaknesses of a theory, is not in itself a sufficient reason to reject the theory. All good theories simplify. Our choice is not between one theory that has costs and weaknesses and another theory that has none, but between theories that make different simplifications. This point is informed by the Kuhnian insight that scientists do not abandon a scientific paradigm just because they have encountered a single anomaly,49 or Lakatos’s insight that theories are not usually falsified by a single experiment.50 Problems and weaknesses of theories accumulate and the latter are usually abandoned only when there is a better or more promising alternative.

For the CPT, this means that we should consider not whether the framework is a simplification of a more complex reality—it is, because all decent theories are—but whether the simplifications that it provides fail to help us understand phenomena of interest, and whether there are better alternatives. My own critique of Mardin’s framework as an instrument of analysis for Turkish politics today is that it may be guilty of the first error (see below), but I am not convinced that there is an equally elegant and persuasive alternative out there yet.

Second, the reason why Mardin’s thesis remains popular is arguably because it has captured a deep fissure in Turkish society, which continues to have political reverberations to this day. Wuthrich’s objections concerning the explanatory power of Mardin’s account notwithstanding, it is hard not to be struck by the explanatory power of the following simple account of late Imperial divisions that seems to presage the rise of political Islam and the AKP in the modern era. Mardin identified

a syndrome that was thereafter often repeated: an effort to Westernize military and administrative organization propounded by a section of the official elite, accompanied by some aping of Western manners, and used by another interest group to mobilize the masses against Westernization.51

The details of these early Westernizing reforms are familiar to students of Turkey: the introduction of the Gregorian calendar and the abolition of the Caliphate; European attire promoted by Atatürk, who toured the country in a top hat; a legal code inspired by the Swiss; public administration reforms that remolded the Ottoman state institutions even if they did not break the continuity; a Turkish version of French laicité; a version of the Latin alphabet, and so on. Nation-building in the Republic was a top-down, state-led endeavor, in which a more secular elite enacted reforms borrowed from the West. And yet, as ambitious and all-encompassing as the reforms were, they failed to fundamentally transform the daily lives of many Turks living in villages and small Anatolian towns, and what change they did bring was often perceived as alien. Kurds rebelled as the Caliphate—a shared source of identification in a multi-ethnic empire—was abolished and various reforms sought to create a Turkish nation.

Partly in response to the resistance to top-down nation-building and Westernizing reforms, the state developed informal power structures that aimed to secure the indivisibility and laic nature of the state against perceived threats, whether they be in the form of alleged foreign imperial designs, domestic separatists, Islamists, or communists. A shadowy network of actors and institutions centered in the national security establishment (especially the National Security Council, Milli Güvenli Kurulu) but including actors in the justice system, the broader bureaucracy, media, and organized crime—sometimes, albeit controversially, called the deep state—established itself as guardians of the secular Turkish state and nation, because the Turkish public constituted ‘a threat to itself’. The existence of a ‘deep state’ is debated,52 but it is commonplace to speak of military tutelage or guardianship.

Moreover, there is recent research that supports the claim that Turkish society and politics is indeed deeply polarized today. As Murat Somer puts it, the research confirms that Turkey is ‘one of the most socially and politically polarized countries in the world.’53 In contemporary Turkish politics, the transition from a parliamentary system to a presidential one has further exacerbated polarization. The parties have been arranged into two main competing coalitions: the (confusingly named) Republican Alliance, Cumhuriyet İttifakı of the ruling AKP and its main ally, the ultranationalist Nationalist Action Party (Millietçi Hareket Partisi, MHP) on one side, and the six-party opposition Nation’s Alliance (Millet İttifakı), on the other. Only the Kurdish-oriented Peoples’ Democratic Party (Halkların Demokratik Partisi, HDP) stays outside any formal alliance, but given that it supports the opposition alliance, there are essentially two camps, ultimately divided by whether they support the sitting President or oppose him.

The President himself is thus a lightning rod for either devotion or loathing, and his electoral strategy in the past few elections has been to fuel this polarization, not try to mitigate it. His rhetoric is often divisive, calling demonstrators ‘vandals’ (çapulcular) and political opponents or critics ‘terrorists’. Much of his rhetoric also plays on an underlying divide between supposedly secular and Westernized elites who do not understand the needs of the real people of Turkey, hardworking and pious men and women of traditional values. This is clearly standard populist rhetoric, but religion and conservatism play a particular role in it and this seems to support the CPT.

This is the case for the continued relevance of Mardin’s thesis. However, if one scratches the surface of Erdoğan’s divisive and populist rhetoric and looks closer at the nature of the relevant political cleavages that underly the polarization that we see today, I believe that one finds that Mardin’s thesis is no longer sufficient to explain contemporary Turkish politics. The next section explores why I believe this is so.

… but no longer good enough?

As most critics have pointed out in one way or another, the binary account of Turkish society and politics is problematically simple. As I have emphasized above, simplicity in itself is not a weakness of a theory but a necessity and in fact a value in itself, ceteris paribus (all other things equal). The problem with the CPT as a framework to understand contemporary Turkish politics is that while it may capture one important dimension, it now obscures other important divisions, and whether those societal divisions reinforce each other or provide cross-cutting cleavages is an empirical question that may vary over time.

The CPT in its modern interpretation of a secular-religious divide is clearly an empirical oversimplification. It does capture one deep and significant dimension in Turkish politics, but not the only one. The surveys of polarization done by the German Marshall Fund54 do show that there is significant psychological distance between supporters of different parties, but it is not binary. Rather, it is a sign of a divisive political culture. As suggested above, the current ordering principle for polarization is support or opposition to President Erdoğan, not religion or conservatism versus secularism. The opposition alliance that is led by secular-oriented CHP includes nationalists, conservatives, and even outright Islamists who defected from the President’s side. That political formation is not easily explained by the CPT.

Moreover, toward the beginning of this essay, I described the political context in which Mardin drafted his article. Since that time, however, the Turkish political landscape has shifted in significant ways that a focus on center-periphery divide cannot easily capture. While Mardin, like Inalcik55 and Erik J. Zürcher56 and other historians, emphasized certain continuities between the late Ottoman Empire and the Republic, Turkey has undergone major transformations that have had an impact on the nature of political cleavages. Developments such as urbanization and migration (both internal and external), industrialization, globalization and the emergence of the internet and social media, the end of the Cold War and shifting international alignments, and political and constitutional changes after coups and other political disruptions all contribute to transforming relevant societal cleavages and resulting political divisions.57

Indeed, one significant such shift is one of the cross-cutting divides that Mardin himself suggested might undermine the explanatory power of his thesis in the future: the rise of the Kurdish movement as a significant political force. While the tentative support by the latest political incarnation of the Kurdish movement (the HDP) for the AKP during its ‘Golden Years’ of reform is in line with an interpretation of two peripheral movements allying against the bureaucratic center, the HDP has since clearly distanced itself from the AKP government. This suggests that the center-periphery axis is no longer sufficient to explain at least one salient dimension of Turkish politics today: the Kurdish issue.

While it might be reasonable to describe the Kurdish movement as part of the ‘periphery’, lumping the militant leftwing Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK) or supporters of the HDP together with the AKP and its base strains the conceptual utility of the periphery to its breaking point. The breakdown of peace talks between the PKK and the state in 2015 led to the worst fighting since the 1990s. The division between politically mobilized Kurds and Turkish nationalists constitutes a major and long-lasting cleavage in Turkish politics that the CPT does not adequately capture. The fact that the HDP, by mutual agreement, stays outside the opposition alliance of six parties even today is indicative of the fact that a binary account is insufficient. As we have already noted, Mardin himself was aware of the potential for Kurdish political mobilization to complicate his thesis, and the eruption of the Kurdish insurgency into a hot conflict with the state that claimed tens of thousands of lives in the 1980s and 1990s validated his prediction.

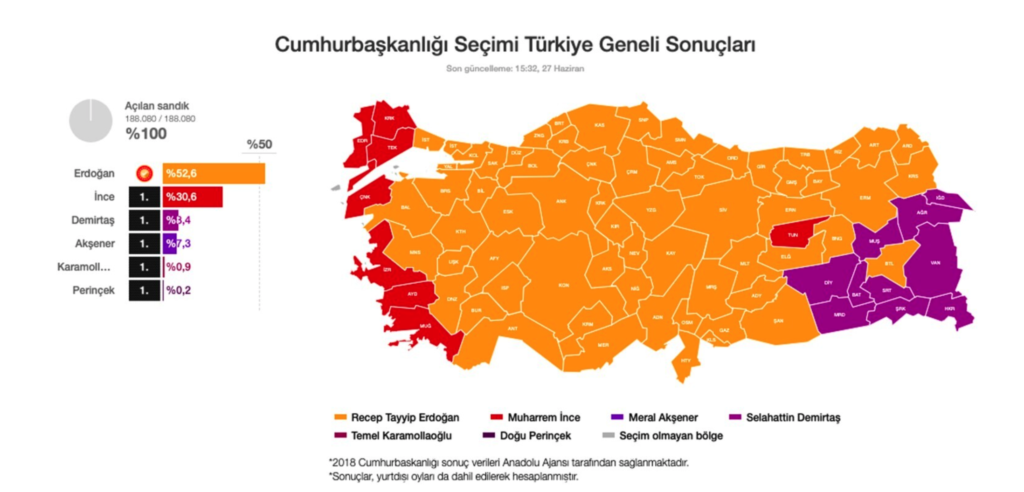

This would seem to suggest that while Turkish party politics today may be polarized between Erdoğan’s supporters and detractors, there is in fact more than one underlying conflict dimensions. Without an increasingly authoritarian president to focus its ire, it is unlikely that the motley opposition coalition of social democratic Kemalists, Islamists, conservatives, and Turkish nationalists, which is also supported by Kurds, would last very long. As we have seen, the two camps today are not best explained by reference to a single divide between a secular center and a religious periphery. The actual electoral map today also suggests a more complex picture, with not two but at least three major geographic clusters (see Figure 2). Throughout much of central Anatolia, the AKP is strongest, with smaller MHP and CHP clusters inserted in a few places. The western coast is dominated by the CHP and the southeast by HDP.

Figure 2. 2018 Turkish Presidential Election Results.

Source: https://www.yenisafak.com/secim-cumhurbaskanligi-2018/secim-sonuclari

A binary framework with one conflict dimension is clearly inadequate to explain this political map. Introducing a second dimension (and a third actor, the HDP) is an improvement. Granted, the geographical pattern is striking and might be taken as an indication that Mardin was on to something when he spoke of Turkish political divisions in spatial terms. However, this observation must be tempered with the realization that the map only indicates which party gained most votes in each province. For example, Mersin is colored orange because the AKP won a plurality of votes, but it obscures the fact that it was a narrow victory. The AKP candidate (Erdoğan) scored only 37.9 percent and CHP’s Muharrem İnce was right behind him, with 37.4 percent. A more detailed map reveals a more complex picture with less clear-cut geographical divisions. 58 This is in line with modern uses of cleavage theory, in which it is seen as the exploration of how different cleavages interact in society rather than the study of one dominant cleavage and its replacement by another.59

In fact, this is neither a new phenomenon nor an original observation on my part. Ersin Kalaycioglu noted in 2006 that the former ‘Center-Periphery kulturkampfs’ had begun fragmenting already by the 1990s and that there had emerged five broad voting blocs in Turkey by then: the ‘Kurdish ethnic nationalists’, the ‘secular bloc’, ‘the sectarian voters of the religious community of the Alevis’, ‘the pious Sunni Turks’ (and Kurds), and ‘ethnic Turkish nationalists’.60

Kalaycioglu, who made good use of Mardin’s framework, also observed that another major change had occurred even earlier. By the early 1970s, ‘agents of the periphery’ had begun penetrating the center, with both Islamic revivalists and ethnic nationalists taking up positions throughout the bureaucracy of the national government.61 The 1980s saw further inclusion of both Turkish ethno-nationalists and Islamists into the political center, which leads to my final observation.

I have left the most obvious objection to the end, so let me conclude with what I believe is an insurmountable problem for the CPT as an analytical framework for understanding Turkish politics today. It is a problem that stems from the single biggest political and societal transformation of Turkey over the past 20 years: the emergence of Erdoğan and the AKP as a ruling party and its consolidation of power. Even for a proponent of Mardin’s thesis, this transformation would constitute an obvious challenge for the framework. One of the leading parties of the (alleged) periphery has now been in power for over two decades. Hence, even if we were to grant the CPT explanatory power for much of the twentieth century and reject all of the criticism outlined above, we would still have to try to accommodate what might be described as a move from periphery to center by the AKP.

With the benefit of hindsight, we can today conclude that the emergence of the AKP as ‘a moderate conservative democratic party’ did not lead to the breakdown of ‘the age-old deep cleavage between secularists and Islamists’ and the consolidation of democracy in Turkey as some hoped.62 Instead, the AKP has both transformed the state and taken over many of its pathologies. A party that claims to represent marginalized peripheral groups has held power for 23 years, purged large parts of the state apparatus that traditionally was considered the bureaucratic ‘center’ and filled it with loyal civil servants, defeated and partially or wholly coopted the national security establishment and so-called ‘deep state,’ and gradually replaced much of the media and business elites in the country. This is such a profound transformation of Turkish politics, society, and economy that Mardin’s CPT can no longer claim to offer a faithful representation of the conflict dimensions that matter. To put it somewhat harshly: the most that the CPT could hope to contribute today in terms of analysis would be an account of the process by which it ceased to matter, namely when a peripheral party captured the political center.

In lieu of a conclusion

I have argued that the extraordinary popularity of the CPT that Serif Mardin laid out in his 1973 article warrants a closer look as we take time to reflect on the first 100 years of the Turkish Republic. The longevity of the thesis is a testament to its ability to combine parsimonious elegance with explanatory power with respect to central tendencies in Turkish politics. Thirty years after publication, it could still claim to offer convincing explanations of key developments such as the rise of Erdoğan’s AKP, a conservative party with roots in political Islam, which claimed to represent the marginalized periphery in Turkish society. I have argued that some of the criticisms often levied at Mardin’s thesis are based on a misunderstanding of the role of simplification in social and political theory, while others point to important shortcomings of the theory without presenting an alternative framework.

This essay does not present an alternative framework either. It merely notes that the anomalies in the framework have by now amassed to the point that it no longer serves as a meaningful approximation of key dynamics in Turkish politics. There is at least one more key dimension than the secular-religious one that more modern interpretations of the CPT emphasize: the Kurdish-Turkish divide. Moreover, the consolidation of the AKP as a dominant ruling party over the course of more than two decades means that what many described as a party from the periphery has established itself in the political center of the country. That development in itself is sufficient to cause a reconsideration of the CPT as a useful tool for understanding Turkish politics today.

That means that we may now stand without an overarching explanatory framework in Turkish studies. Some may see this as a good thing, others would decry it as a problem. Regardless of one’s inclination in this respect, there is room for entrepreneurial scholars to come up with new and convincing accounts of the turbulent politics of the Turkish Republic at the eve of its centenary.

Notes

2 Wuthrich, “An Essential,” 751.

3 Gürhanli, Beyond Populism, 27.

4 Arat, “Toward a Democratic Society”; Bilgin, The International; Ciddi, Kemalism in Turkish Politics; Çarkoglu, “The Rise”, and “The Nature”; Grigoriadis, “Islam and Democratization”; Gülalp, “Globalization”, and Kimlikler siyaseti; Gözaydin, Diyanet; Hale, Turkish Politics; Heper, The State and Kurds; Kadioglu, “The Paradox”; Kalaycıoglu, “Elections” and Turkish Dynamics; Kaliber, “Securing the Ground”; Kasaba, A Moveable Empire; Kaya, Europeanization; Sayarı, “The Turkish Party System”; Somer, “Moderation” and “Turkey: The Slippery Slope”; Yavuz, “Political Islam”; Öniş, “The triumph”; Özbudun, “Changes and Continuities” and “From Political Islam”.

6 This brief biographical section draws upon publicly available information such as Mardin’s Wikipedia page and obituaries, such as https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20170907-serif-mardin-leading-turkish-sociologist-dies-at-90/, https://t24.com.tr/k24/yazi/serif-mardin,1402 and https://trdergisi.com/bir-munevver-portresi-serif-mardin/.

7 Mardin, “Center-Periphery,” 186.

22 Bakiner notes that Mardin in several interviews expressed a wish that scholars would refrain from using his model unreflectively, describing his model only as a “’very soft metaphor’ that should be reappraised in light of recent empirical developments.” Bakiner, “A Key,” 508.

23 Mardin, “Center-Periphery,” 187.

24 Gürhanli, Beyond Populism. In the tradition of Nordic academia, I had the honor of serving as the “opponent”, or discussant on this dissertation.

26 Güngem and Ertem, “Approaches,” 1.

28 Lipset and Rokkan, “Cleavage Structures,” 14.

29 Inalcik, “Political Modernization,” 60, 63.

30 Gülalp, “Globalization,” 343.

33 Erdoğan quoted in Gürhanli, Beyond Populism, 193.

35 The term “Liberal” in the Turkish context is often used to denote a heterogenous group of progressive intellectuals who rejected Kemalist nationalism in favor of greater pluralism and democracy, not necessarily individuals aligned with either American left liberalism or British classical liberalism as an ideology. See Karlsson, Liberal Intellectuals.

37 Özbudun, “From Political Islam,” 555.

39 Öniş, and Yilmaz, “Between Europeanization.”

41 While one of the co-leaders of the pro-Kurdish HDP, Selahattin Demirtaş, announced late in the campaign that it would not support the proposal, the real break between the HDP and the AKP arguably came later, in 2015. Around the time of the referendum, the AKP government had been pursuing peace with the PKK and the Kurdish movement could reasonably be described as hesitant but still cautiously hopeful about the AKP at the time.

42 Özbudun, “Turkey’s Constitutional Reform.”

46 See e.g., Epstein, “The Principle.”

48 Walsh, “Occam’s Razor: A Principle.”

51 Mardin, “Center-Periphery,” 175.

52 Günter, “Turkey, Kemalism,” The existence of a so-called ‘deep state’ in Turkey is controversial and by its nature difficult to establish, but the notion has now arguably become an established term also in scholarly studies. See Söyler, “Informal institutions”; Gingeras, “Last Rites” and “In the Hunt”; and Watmough, Democracy in the Shadow.

53 Somer, “Turkey,” 42. See also Çelik, Bilali and Iqbal, “Patterns”; Aydin-Düzgit and Balta, “When Elites”; and German Marshall Fund in Turkey, “Dimensions.”

54 German Marshall Fund, “Dimensions.”

55 Inalcik, “Political Modernization.”

57 See Kalaycioglu, Turkish Dynamics for an overview of some of these changes.

58 Natali Arslan and Efe Kerem Sözeri commented on this on the independent news platform P24. See “Turkey’s Parliamentary Election 2015.” P24, 16 November 16, 2015, available at http://platform24.org/en/articles/325/turkey-s-parliamentary-election-2015

59 See Hooghe and Marks, “Cleavage theory.”

60 Kalaycioglu, Turkish Dynamics, 136–7.

62 Özbudun, “From Political Islam,” 555.

Paul T. Levin is Director of the Stockholm University Institute for Turkish Studies and Director of the Consortium for European Symposia on Turkey (CEST). He is an Associate Researcher at the Swedish Institute for International Affairs and Fellow at the Swedish Research Institute in Istanbul. Dr. Levin is Docent in International Relations (IR), with a Ph.D. in IR and an M.A. in Political Science from the University of Southern California.