Turkey (Türkiye): Background and U.S. Relations In Brief

Updated January 19, 2023

U.S. relations with Turkey (Türkiye) take place within a complicated geopolitical environment and with Turkey in economic distress. U.S.-Turkey tensions that worsened after a failed 2016 coup in Turkey—including ongoing disagreements over Syrian Kurds and Turkey’s 2019 procurement of a Russian S-400 surface-to-air defense system—highlight uncertainties about the future of bilateral relations. Congressional actions have included sanctions legislation and informal holds on U.S. arms sales. Nevertheless, U.S. and Turkish officials emphasize the importance of continued cooperation and Turkey’s membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Observers voice concerns about the largely authoritarian rule of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Major inflation and a sharp decline in Turkey’s currency have led to speculation that Erdogan and his Justice and Development Party (Turkish acronym AKP) might be vulnerable to a coalition of opposition parties in presidential and parliamentary elections planned for June 2023 if competitive elections occur. If a different Turkish president were to win 2023 elections and take power, some domestic and foreign policy changes could be possible.

U.S. relations and F-16s. Under President Joe Biden, existing U.S.-Turkey tensions have continued alongside cooperation on other foreign policy matters. While deepening ties with Russia remain a cause for U.S. concern, Turkey’s emergence as a mediator between Russia and Ukraine after Russia’s 2022 invasion has arguably increased Turkey’s importance for U.S. policy. U.S.-Turkey relations have improved somewhat due to Turkey’s cautious support for Ukraine’s defense; growing relationships with other countries that seek to counter Russian regional power (including via the export of drone aircraft); and openness to rapprochement with Israel, some Arab states, and Armenia. President Biden has voiced support for sales thatwould upgrade Turkey’s aging F-16 fleet, but some Members of Congress have expressed opposition. According to media accounts, the Administration reportedly provided informal notification to Congress in January 2023 of possible sales of F-16s to Turkey, plus associated equipment and munitions. Factors potentially influencing congressional deliberations include Turkey’s tense relations with Greece and its stance on Sweden’s and Finland’s NATO accession. Congressional and executive branch action regarding Turkey and its rivals could have implications for bilateral ties and U.S. political-military options in the region, and Turkey’s strategic orientation. The following are key factors in the U.S.-Turkey relationship.

Turkey’s foreign policy approach. For decades, Turkey has relied closely on the United States and NATO for defense cooperation, European countries for trade and investment, and Russia and Iran for energy imports. Turkish leaders have indicated an interest in reducing their dependence on the West, and that may partly explain their willingness to coordinate some actions with Russia. Nevertheless, Turkey retains significant differences with Russia in Syria, Ukraine, Libya, and Armenia-Azerbaijan.

Major issues: Russia, Sweden-Finland-NATO, and Greece. In the wake of Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Turkey faces challenges in balancing its relations with the two countries and managing Black Sea access, with implications for U.S.- Turkey ties. To some extent, Erdogan has sought to reinforce Turkey’s embattled economy by deepening economic and energy ties with Russia. Erdogan might assess that Western sanctions against Russia give Turkey increased leverage in these dealings. At the same time, Turkey has expanded defense cooperation with Ukraine. Turkey has become an important mediator between Russia and Ukraine on brokering a grain export corridor and other issues. In June, Turkey agreed on a framework deal for Sweden and Finland to join NATO, but Turkey has delayed ratifying their accession while demanding that the two countries help Turkey act against people it considers to be terrorists. Longstanding disputes between Greece and Turkey over territorial rights in the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean seas spiked in 2022 amid greater U.S. strategic cooperation with Greece.

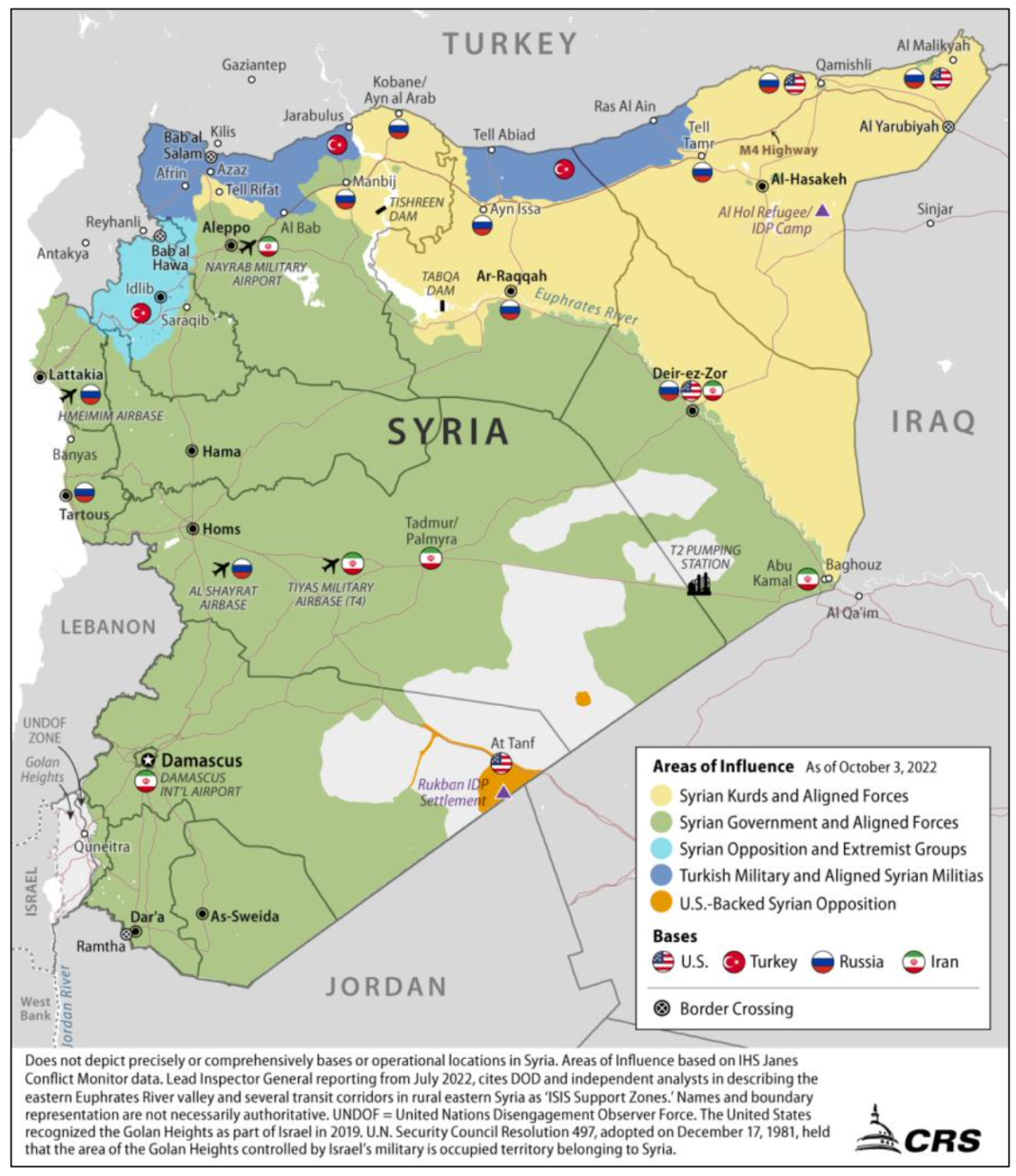

Syria: ongoing conflict near borders. Turkish concerns regarding its southern border with Syria has deepened further during Syria’s civil war, due largely to (1) the flow of nearly four million refugees into Turkey, (2) U.S. efforts to counter the Islamic State by working with Syrian Kurds linked to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (Kurdish acronym PKK, a U.S.- designated terrorist organization), and (3) the presence of Russian, American, and Iranian forces in Syria that complicate and somewhat constrain Turkish action. Turkey and allied Syrian armed opposition groups have occupied various areas of northern Syria since 2016, and Turkey’s military continues to target Kurdish fighters in Syria and Iraq. Turkey’s military could undertake another ground operation against the PKK-linked Syrian Kurds, despite reported U.S. and Russian expressions of concern.

This report provides background information and analysis on key issues affecting U.S.-Turkey (Türkiye)[1] relations, including domestic Turkish developments and various foreign policy and defense matters. U.S. and Turkish officials maintain that bilateral cooperation on regional security matters remains mutually important,[2] despite Turkey’s purchase of an S-400 surface-to-air defense system from Russia and a number of other U.S.-Turkey differences (such as in Syria and with Greece and Cyprus).

Introduction and Key U.S.-Turkey Considerations

Under President Joe Biden, some existing U.S.-Turkey tensions have continued alongside cooperation on other matters and opportunities to improve bilateral ties. While continued or deepening ties with Russia in certain areas remain a cause for concern for the Biden Administration and some Members of Congress, Turkey’s cautious support for Ukraine’s defense and openness to rapprochement with Israel, some Arab states, and Armenia have somewhat improved U.S.-Turkey relations.[3] President Biden has expressed support for selling F-16s to Turkey, and in January 2023 the Administration reportedly informally notified Congress of a potential F-16 sale, plus associated equipment and munitions (see “Possible F-16 Sales and Congressional Views” below).

Members of Congress may consider legislative and oversight options regarding Turkey. Congressional and executive branch action regarding Turkey and its rivals could have implications for bilateral ties, U.S. political-military options in the region, and Turkey’s foreign policy orientation and financial well-being.

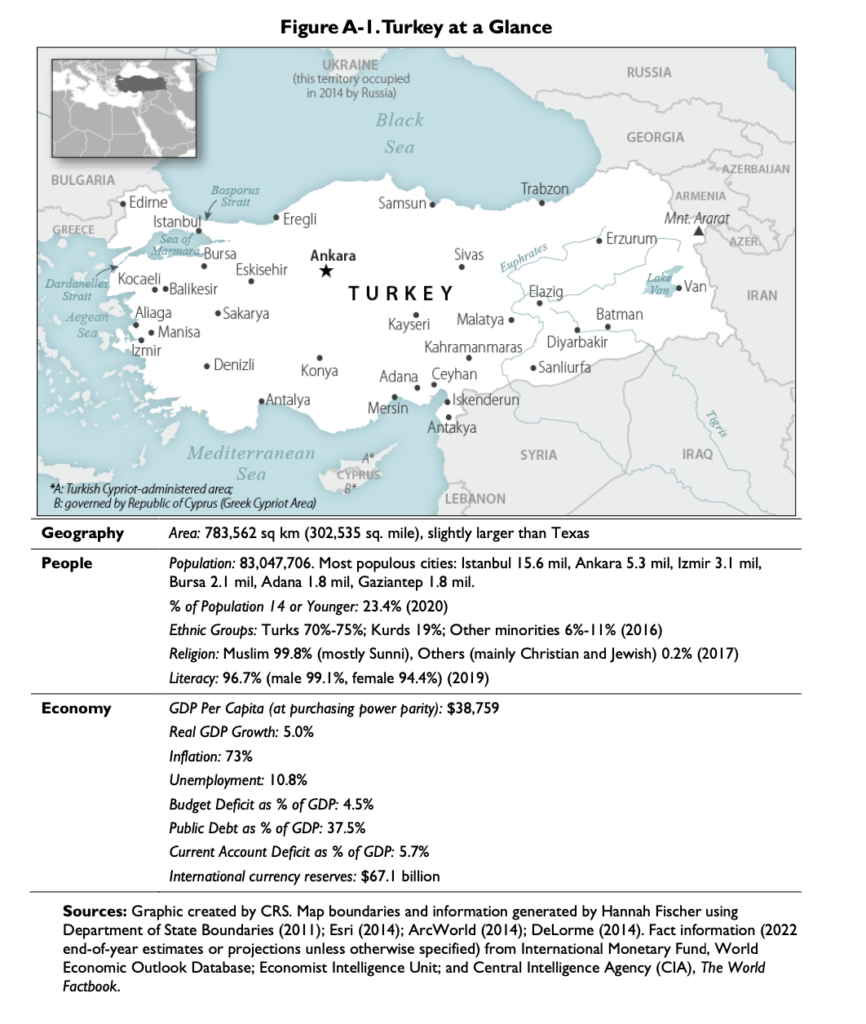

For additional information, see CRS Report R41368, Turkey (Türkiye): Background and U.S. Relations, by Jim Zanotti and Clayton Thomas. See Figure A-1 for a map and key facts and figures about Turkey.

Domestic Issues

Political Developments Under Erdogan’s Rule

President Erdogan has ruled Turkey since becoming prime minister in 2003, and has steadily deepened his control over the country’s populace and institutions. After Erdogan became president in August 2014 via Turkey’s first-ever popular presidential election, he claimed a mandate for increasing his power and pursuing a presidential system of governance, which he cemented in a 2017 referendum and 2018 presidential and parliamentary elections. Some allegations of voter fraud and manipulation surfaced after the referendum and the elections.[4] Since a failed July 2016 coup attempt by elements within the military, Erdogan and his Islamist- leaning Justice and Development Party (Turkish acronym AKP) have adopted more nationalistic domestic and foreign policy approaches, perhaps partly because of their reliance on parliamentary support from the Nationalist Action Party (Turkish acronym MHP).

Many observers describe Erdogan as a polarizing figure, and elections have reflected roughly equal portions of the country supporting and opposing his rule.[5] The AKP won the largest share of votes in 2019 local elections, but lost some key municipalities, including Istanbul, to candidates from the secular-leaning Republican People’s Party (Turkish acronym CHP).

U.S. and European Union (EU) officials have expressed a number of concerns about authoritarian governance and erosion of rule of law and civil liberties in Turkey.[6] Some leading opposition figures in Turkey have accused Erdogan of planning, controlling, and/or using the failed coup to suppress dissent and consolidate power.[7]

Meanwhile, Turkish authorities have continued their on-and-off efforts to counter militants from the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (Kurdish acronym PKK, a U.S.-designated terrorist organization). These efforts include Turkish military operations targeting PKK and PKK-aligned personnel in Iraq and Syria.[8]

Major Economic Challenges

Ongoing economic problems in Turkey considerably worsened in 2022 as its currency, the lira, depreciated in value around 28% against the U.S. dollar, after declining by nearly 45% in 2021. Official annual inflation climbed to nearly 85% for October—a level not seen in Turkey since the 1990s—before dropping to 64% in December.[9] Some unofficial estimates have suggested that actual inflation may be well over 100%.[10] Many analysts link the spike in inflation to the Turkish central bank’s repeated reductions of its key interest rate since September 2021, with additional inflationary pressure possibly coming from external events such as Russia’s war on Ukraine and interest rate hikes in the United States and other major economies.[11] The lira has been trending downward for more than a decade, with its decline probably driven in part by broader concerns about Turkey’s rule of law and economy.[12]

Throughout this time, President Erdogan has assertively challenged the conventional economic theory that higher interest rates stem inflation, attract foreign capital, and support the value of the currency. In replacing Turkey’s central bank governor and finance minister in 2021, Erdogan established greater control over Turkish fiscal and monetary policy. In public statements, Erdogan has argued that lower interest rates boost production, employment, and exports.[13] Erdogan also has criticized high interest rates as contrary to Islamic teachings and as exacerbating the gap between rich and poor.[14]

The currency and inflation crisis in Turkey has dramatically affected consumers’ cost of living and the cost of international borrowing (mostly conducted in U.S. dollars) for banks and private sector companies. The government has sought to stop or reverse inflation by providing tax cuts, minimum wage increases, and subsidies for basic expenses, along with borrowing incentives for banks that hold liras.[15] Turkey also has sought currency swaps from some Arab Gulf states, and has benefitted from Russian-origin inflows that contribute to U.S. warnings about potential sanctions evasion (see “Turkey-Russia Economic and Energy Cooperation” below).[16] He has publicly rejected calls to turn to the International Monetary Fund for a financial assistance package.

2023 Elections

Turkey’s next presidential and parliamentary elections are planned to take place by June 2023, but probably will happen in May. Erdogan or Turkey’s parliament can change the elections to an earlier date.[17] In January 2023, Erdogan signaled that elections would likely take place on May 14, 2023.[18] If no presidential candidate receives more than 50% of the vote, a presidential run-off election between the top two vote-getting candidates would take place two weeks later.

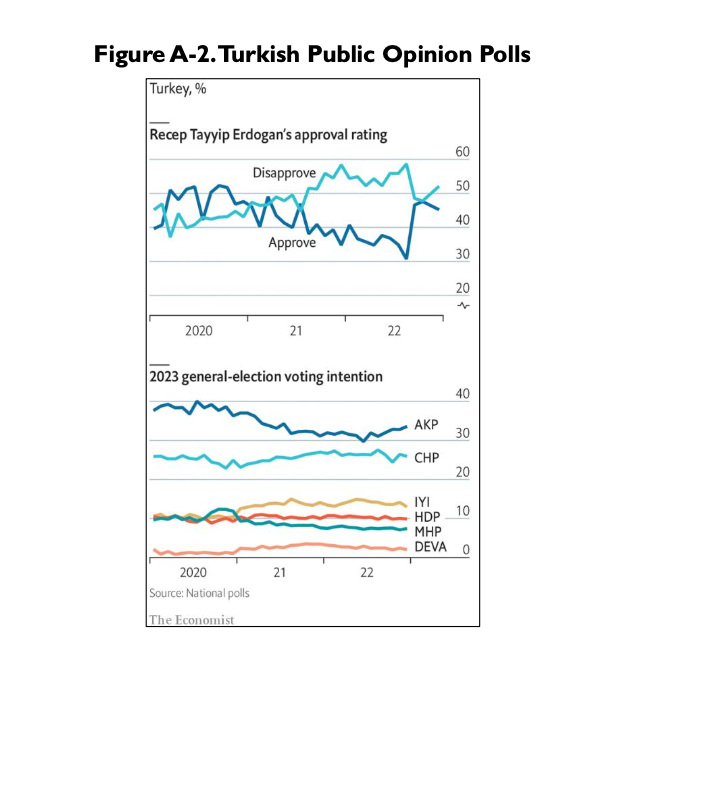

Largely in the context of Turkey’s economic problems discussed above, public opinion polls have fueled speculation that Erdogan and the AKP-MHP parliamentary coalition might be vulnerable to a coalition of opposition parties including the CHP, the Iyi (Good) Party, and the Democracy and Progress Party (Turkish acronym DEVA) (see Figure A-2).[19] Some observers have debated whether (1) free and fair elections could take place under Erdogan,[20] (2) opposition parties can convince potential swing voters to side with them despite their personal or ideological affinity for Erdogan,[21] or (3) Erdogan would cede power after an electoral defeat.[22]

The CHP and some other opposition parties have agreed on some steps toward a joint platform focused on returning Turkey to the parliamentary system that existed before the 2018 election, largely as a means of limiting executive power.[23] However, it remains unclear which opposition candidate will challenge Erdogan for president: CHP party leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu (from the Alevi religious minority), or either of the two mayors who won control of Istanbul and Ankara for the party in 2019 (Ekrem Imamoglu and Mansur Yavas, respectively) and generally poll higher than Kilicdaroglu.[24] Opposition figures have criticized the Erdogan government’s approach to a range of foreign and domestic policy issues and promised to make changes (see also “Foreign Policy Changes Under a Different President?”).[25] Imamoglu’s candidacy may be jeopardized by a criminal conviction (see text box).[26] Despite Erdogan’s potential vulnerability, some observers have questioned the opposition coalition’s prospects, citing obstacles posed by disunity, Erdogan’s political resilience, and the government’s influence over the media, economic developments, and judicial rulings.[27]

Imamoglu’s Criminal Case and Potential Political Ban

Istanbul mayor and CHP member Ekrem Imamoglu could face a ban from political activity because of a December 2022 criminal conviction. The charge of insulting members of Turkey’s Supreme Electoral Council stemmed from a remark that Imamoglu said he made about the annulled March 2019 election (discussed above) in response to an insult against him from Turkey’s interior minister.[28] The court sentenced Imamoglu to jail and banned him from political activity for two years and seven months, but both penalties are subject to appeal, and the timing of the appellate process is unclear.[29] In the meantime, Imamoglu continues to serve as mayor and engage politically. Imamoglu and other opposition figures denounced the verdict and judicial process as politicized and a sign of government attempts to sideline Erdogan’s potential electoral opponents.[30] The State Department issued a statement criticizing Imamoglu’s conviction, and urging the government to cease prosecutions under criminal insult laws.[31]

In a separate case, Turkish prosecutors charged Imamoglu (and six co-workers) in January 2023 with improperly awarding a public tender to a company during his time as mayor of an Istanbul district (before he was elected mayor of the entire city).[32] Imamoglu has called the charges “an attempt to fabricate a bogus criminal offence,” saying that authorities had not detected anything problematic at the time of the tender.[33]

How Kurdish citizens of Turkey (numbering nearly 20% of the population) vote could impact the outcome.[34] The Kurdish-led Peoples’ Democratic Party (Turkish acronym HDP), which could face a legal ban,[35] announced in January 2023 that it would run its own presidential candidate in the elections.[36] Pending resolution of the potential legal ban, Turkey’s Constitutional Court has frozen the HDP bank accounts that hold the party’s state-provided funds.[37]

Turkish Foreign Policy General Assessment

Turkey’s strategic orientation, or how it relates to and balances between the West and other global and regional powers, is a major consideration for the United States. Trends in Turkey’s relations with the United States and other countries reflect changes to this orientation, as Turkey has sought greater independence of action as a regional power within a more multipolar global system. Turkish leaders’ interest in reducing their dependence on the West for defense and discouraging Western influence over their domestic politics may partly explain their willingness to coordinate some actions with Russia, such as in Syria and with Turkey’s purchase of a Russian S-400 surface-to-air defense system. Nevertheless, Turkey retains significant differences with Russia— with which it has a long history of discord—including in political and military crises involving Syria, Ukraine, Libya, and Armenia-Azerbaijan.

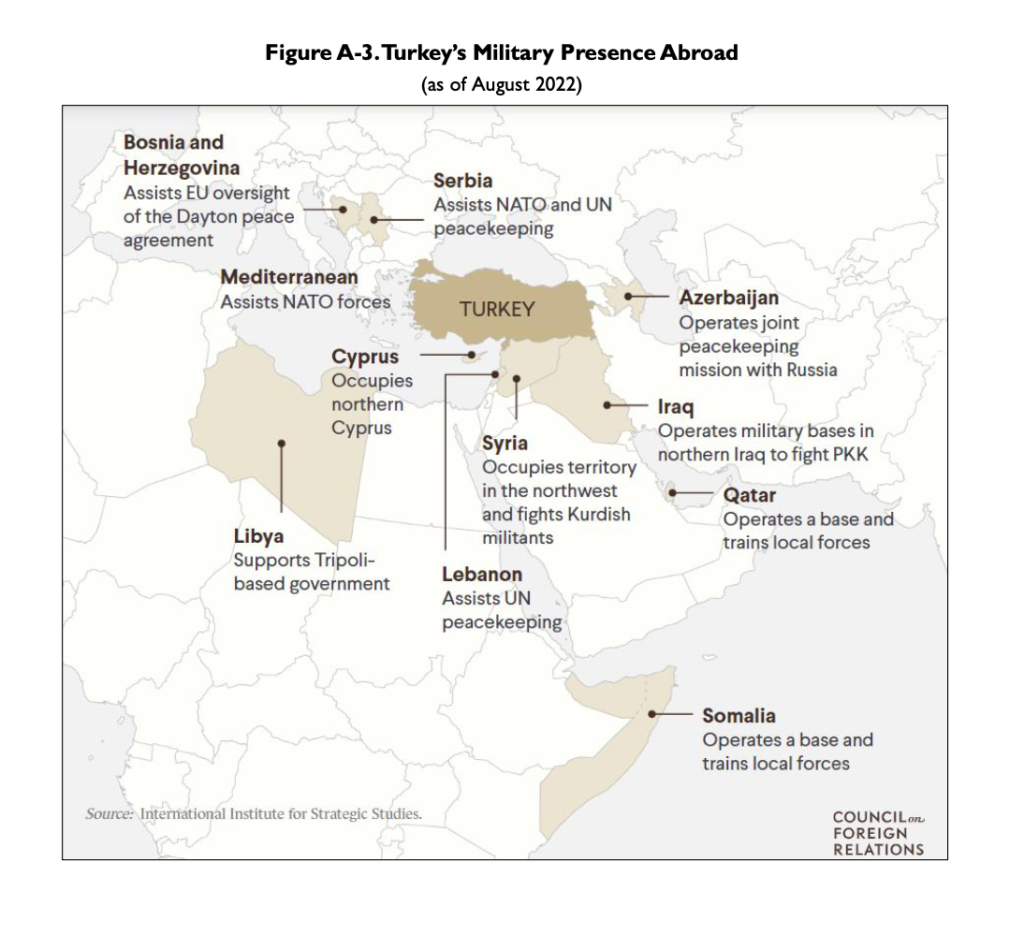

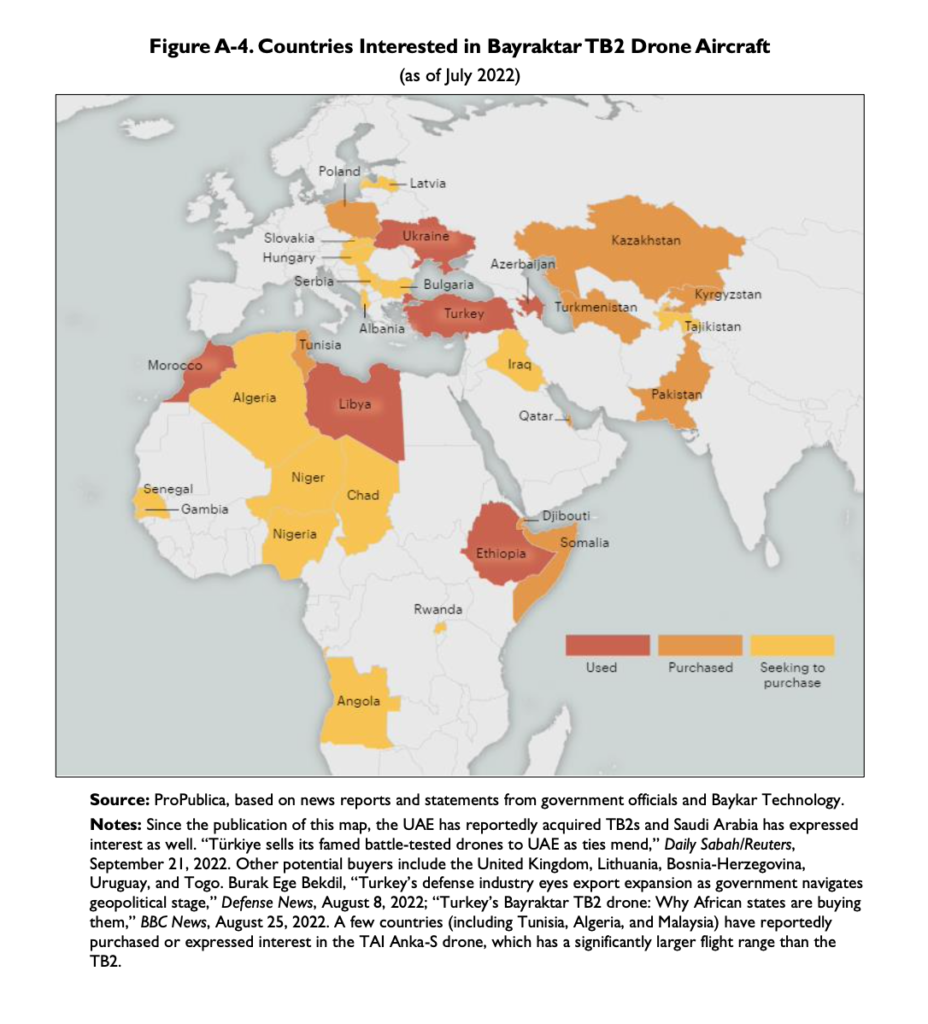

In recent years, Turkey has involved its military in the Middle East, Eastern Mediterranean, and South Caucasus in a way that has affected its relationships with the United States and other key actors (Figure A-2). Turkey appears to be building regional relationships partly due to its export of the popular Bayraktar TB2 drone (see Figure A-4), but some observers have raised concerns that “drone diplomacy” could possibly enable human rights violations or lead to other adverse consequences for Turkey’s interests or those of its allies and partners.[38] U.S. officials have sometimes encouraged cooperation among other allies and partners to counter Turkish actions.[39] In the past year, however, Turkey has taken some steps to ease tensions with major U.S. partners in the Middle East—namely Israel, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia.[40] U.S. and Turkish officials maintain that bilateral cooperation on regional security matters remains mutually important.[41]

Turkish leaders appear to compartmentalize their partnerships and rivalries with other influential countries as each situation dictates, partly in an attempt to reduce Turkey’s dependence on these actors and maintain its leverage with them.[42] For decades, Turkey has relied closely on the United States and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) for defense cooperation, European countries for trade and investment (including a customs union with the EU since the late 1990s), and Russia and Iran for energy imports.

Without a means of global power projection or major natural resource wealth, Turkey’s military strength and economic well-being appear to remain largely dependent on these traditional relationships. Turkey’s ongoing economic struggles (discussed above) highlight the risks it faces if it jeopardizes these ties.[43] Turkey’s future foreign policy course could depend partly on the degree to which Turkish leaders feel constrained by their traditional security and economic relationships with Western powers, and how willing they are to risk tensions or breaks in those relationships while building other global relationships.

Foreign Policy Changes Under a Different President?

In anticipation of 2023 elections, observers have speculated about how a new president’s foreign policy (including domestic policy with clear foreign policy ramifications) might differ from Erdogan’s if an opposition candidate wins.[44] Because of widespread nationalistic sentiment among Turkey’s population and most of its political parties, a different president may have difficulty changing Turkish policies on some of the following matters of core security concern: Syria and Iraq (Kurdish militancy, refugee issues, and other countries’ influence), Greece and Cyprus (Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean disputes), and Russia and Ukraine (conflict and its regional and global consequences).

However, a different president may be more likely to alter certain ongoing policies that may be more reflective of Erdogan’s or the AKP’s preferences than of broad national consensus. Such changes may include (1) providing more flexibility to central bankers and other officials on monetary policy decisions and other measures to address Turkey’s economic problems, (2) giving greater consideration to European Court of Human Rights rulings, and (3) reducing Turkish

support for Sunni Islamist groups like Hamas (a U.S.-designated terrorist organization), the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, and Syrian armed opposition factions.

Some Turkish opposition parties’ foreign policy statements suggest that a different president might be less willing than Erdogan to say and do things that risk harming relationships with the United States and European countries.[45] Thus, despite the difficulties that may surround changing some policies (as mentioned above), a different Turkish president could conceivably be less inclined toward implementing those policies in a way that might worsen relations with Western states, such as by pursuing additional arms purchases from Russia or new military operations in northern Syria or the Aegean/Eastern Mediterranean area. However, if a new, untested Turkish government feels pressure to signal its strength to various international actors or to placate multiple domestic constituencies within a coalition, that president may strive to match Erdogan’s reputation for assertiveness. Conversely, a president facing lack of consensus within a coalition might become more passive on foreign policy.

U.S./NATO Strategic Relationship and Military Presence

The United States has valued Turkey’s geopolitical importance to and military strength within the NATO alliance, while viewing Turkey’s NATO membership as helping anchor Turkey to the West. For Turkey, NATO’s traditional importance has been to mitigate Turkish concerns about encroachment by neighbors, such as the Soviet Union’s aggressive post-World War II posturing leading up to the Cold War. In more recent or ongoing arenas of conflict like Ukraine and Syria, Turkey’s possible interest in countering Russian objectives may be partly motivating its military operations and arms exports.[46]

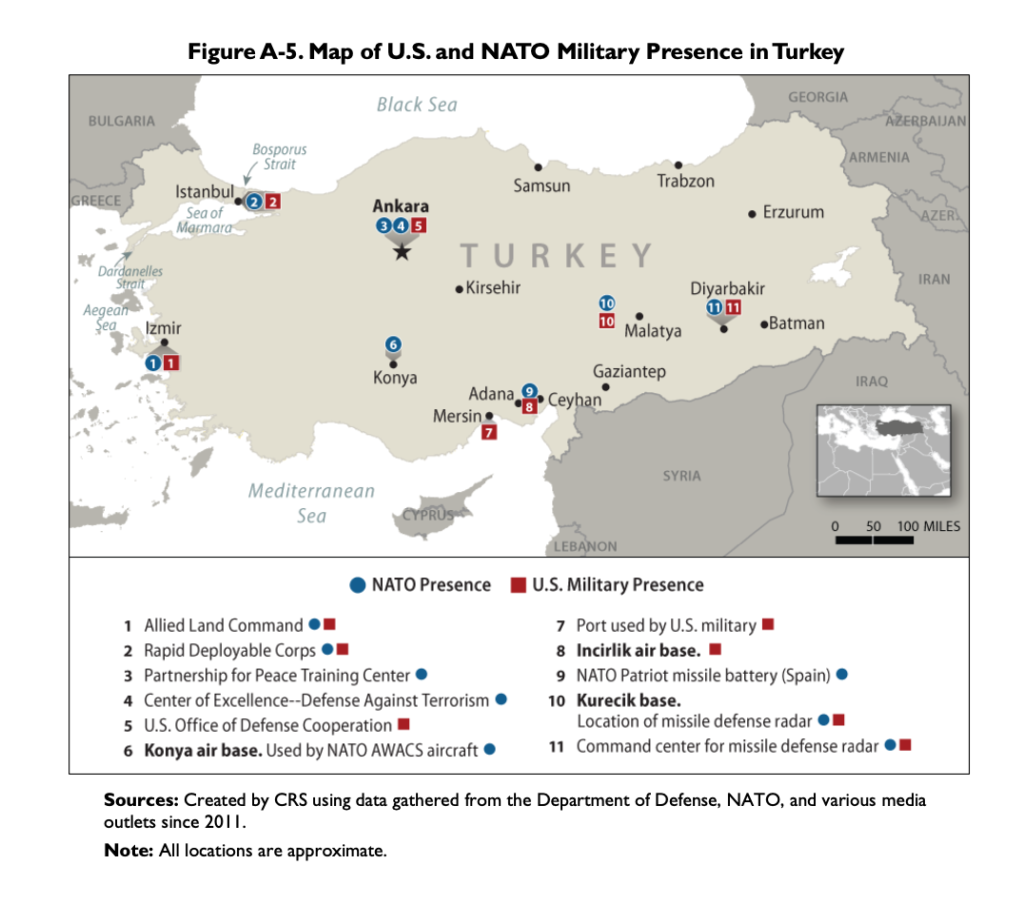

Turkey’s location near several conflict areas has made the continuing availability of its territory for the stationing and transport of arms, cargo, and personnel valuable for the United States and NATO. In addition to Incirlik Air Base near the southern Turkish city of Adana, other key U.S./NATO sites include an early warning missile defense radar in eastern Turkey and a NATO ground forces command in Izmir (see Figure A-5). Turkey also controls access to and from the Black Sea through the Bosphorus and Dardanelles Straits (the Straits—see Figure A-6).

Tensions between Turkey and other NATO members have fueled internal U.S./NATO discussions about the continued use of Turkish bases. Some observers have advocated exploring alternative basing arrangements in the region.[47] Some reports suggest that expanded or potentially expanded U.S. military presences in places such as Greece, Cyprus, and Jordan might be connected with concerns about Turkey.[48] In March 2022 congressional hearing testimony, Turkey expert and former congressional committee staff member Alan Makovsky said that while the United States should make efforts to keep Turkey in the “Western camp,” Turkish “equivocation in recent years” justifies the United States building and expanding military facilities in Bulgaria, Romania, and Greece to “hedge its bets.”[49]

Russia

Turkey’s relations with Russia feature elements of cooperation and competition. Turkey has made a number of foreign policy moves since 2016 toward closer ties with Russia. These moves could be motivated by a combination of factors, including Turkey’s effort to reduce dependence on the West, economic opportunism, and chances to increase its regional influence at Russia’s expense. Turkey also has moved closer to a number of countries surrounding Russia—including Ukraine and Poland—likely in part as a counterweight to Russian regional power.[50]

Russia’s 2022 Invasion of Ukraine and Turkish Mediation Efforts

Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine has heightened challenges Turkey faces in balancing its relations with the two countries, with implications for U.S.-Turkey ties. Turkey’s links with Russia—especially its 2019 acquisition of a Russian S-400 system—have fueled major U.S.- Turkey tensions, triggering sanctions and reported informal congressional holds on arms sales (discussed below). However, following the renewed Russian invasion of Ukraine, U.S. and Turkish interests in countering Russian revisionist aims—including along the Black Sea coast— may have converged in some ways as Turkey has helped strengthen Ukraine’s defense capabilities in parallel with other NATO countries.[51] In addition to denouncing Russia’s invasion, closing the Straits to belligerent warships, and opposing Russian claims to Ukrainian territory (including Crimea),[52] Turkey has supplied Ukraine with armed drone aircraft and mine-resistant ambush-resistant (MRAP) vehicles, as well as humanitarian assistance.[53] Nevertheless, Turkey’s leaders likely hope to minimize spillover effects to Turkey’s national security and economy, and this might partly explain Turkey’s continued engagement with Russia and desires to help mediate the conflict (discussed below).

In January 2023, a media outlet reported that Turkey began transferring some dual-purpose improved conventional munitions (or DPICMs, which are artillery-fired cluster munitions) to Ukraine in November 2022. The report cited various observers debating the potential battlefield impact and humanitarian implications of the weapon’s use.[54] Turkish and Ukrainian officials have denied that any such transfers have occurred.[55]

Turkey-Ukraine Defense Cooperation

Turkey and Ukraine have strengthened their relations since Russia’s invasion of Crimea in 2014.[56] In 2017, a Turkish security analyst attributed these closer ties to growing mutual interests in countering Russian influence in the Black Sea region and in sharing military technology to expand and increase the self-sufficiency of their respective defense industries.[57] Since 2020, the two countries have signed multiple agreements signifying closer cooperation, and also signed a broader free trade agreement (pending ratification) in February 2022.[58]

In line with these agreements, Turkish and Ukrainian companies have engaged in or planned a significant expansion of defense transactions, including a number of joint development or co-production initiatives.[59] Turkish expertise with drone and other aircraft and naval platforms complements Ukrainian skills in designing and constructing aerospace engines and missiles.[60] As part of the deepening bilateral defense cooperation, Turkey has sold several Turkish-origin Bayraktar TB2 drones to Ukraine since 2019,[61] and some reports have suggested that the manufacturer has delivered additional TB2s to Ukraine at various times since Russia’s 2022 invasion.[62] Additionally, Turkey is helping establish Ukraine’s naval capabilities by producing corvettes (small warships) for export.[63]

Turkey’s maintenance of close relations with both Russia and Ukraine, and its ability to regulate access to the Straits has put it in a position to mediate between the parties on various issues of contention. In July 2022, Turkey and the United Nations entered into parallel agreements with Russia and Ukraine to provide a Black Sea corridor for Ukrainian grain exports that could partly alleviate global supply concerns.[64] Under the deal, which currently runs until March 2023, Turkey, Russia, Ukraine, and the U.N. have representatives at a joint coordination center in Istanbul to oversee implementation and inspect ships to prevent weapons smuggling.[65] President Biden has expressed appreciation for Turkey’s efforts.[66]

Turkey-Russia Economic and Energy Cooperation

Turkish officials have sought to minimize any negative economic impact Turkey might face from the Russia-Ukraine war, partly through boosting various forms of economic and energy cooperation with Russia. These efforts may stem from Turkish leaders’ concerns about improving the country’s economic profile in advance of 2023 elections.[67] The Turkish government has not joined economic sanctions against Russia or closed its airspace to Russian civilian flights.

In August 2022, Presidents Erdogan and Putin publicly agreed to bolster Turkey-Russia cooperation across economic sectors.[68] Turkey’s Russia-related dealings could potentially lead to Western secondary sanctions against Turkey for facilitating Russian sanctions evasion. In June 2022, Deputy Secretary of the Treasury Wally Adeyemo reportedly visited Turkey to raise concerns over the movement of some Russian assets and business operations to Turkey,[69] and in August Adeyemo sent a letter to Turkish business groups warning of penalties if they worked with Russian individuals or entities facing sanctions.[70]

NATO Accession Process for Sweden and Finland

Sweden and Finland formally applied to join NATO in May 2022, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Turkey objected to the formal start of the two countries’ accession process, delaying it for more than a month. Under Article 10 of the North Atlantic Treaty, the admission of new allies requires the unanimous agreement of existing members.

The Turkish objections centered around claims that Sweden and Finland have supported or harbored sympathies for groups that Turkey deems to be terrorist organizations, namely the Fethullah Gulen movement[71] (which Turkey’s government has blamed for involvement in the 2016 failed coup) and the PKK.[72] (The United States and EU also classify the PKK as a terrorist group.) Turkey demanded that both countries lift the suspension of arms sales they had maintained against Turkey since its 2019 incursion into Syria against the PKK-linked Kurdish group (the People’s Protection Units—Kurdish acronym YPG) that has partnered with the U.S.- led anti-Islamic State coalition.[73] Turkey removed its objections to starting the accession process after NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg mediated a June 2022 agreement between Turkey, Sweden, and Finland. In the trilateral agreement, the three countries confirmed that no arms embargoes remain in place between them. Further, Sweden and Finland agreed not to support the YPG or Gulen movement, and pledged to work against the PKK.[74]

While Turkey’s decision generally drew plaudits from other NATO members, during the delay some Western officials had raised questions about Turkey’s commitment to strengthening NATO. Since then, President Erdogan has sought to have Sweden and Finland take additional steps before Turkey’s parliament considers ratifying the two countries’ accession.[75] With Hungary likely to ratify Swedish and Finnish accession by early 2023, Turkey could remain the only country delaying the process.[76]

For example, Turkey continues to press Sweden and Finland to extradite people that Turkey considers to be terrorists. Under the June 2022 trilateral agreement, Sweden and Finland agreed to address Turkey’s pending deportation or extradition requests in various ways, but did not commit to specific outcomes in those cases.[77] In December, Sweden reportedly deported a man who had been convicted in Turkey in 2015 of being a PKK member,[78] but Sweden’s supreme court blocked the extradition of a journalist with alleged links to the Gulen movement.[79] Sweden’s prime minister and other sources have indicated that neither Sweden nor Finland are inclined to make political decisions on extradition that contravene domestic judicial findings conducted under due process and the rule of law.[80] An unnamed European diplomat was quoted in November as saying, “It remains to be seen if Erdogan thinks he’s got enough signs of goodwill from Sweden and it’s therefore in his political and military interest to declare victory, or if he thinks sticking to the current line will serve his re-election campaign.”[81]

At a December press conference with Sweden’s and Finland’s foreign ministers, Secretary of State Blinken reiterated strong U.S. support for the two countries’ NATO accession and said that they have addressed Turkey’s security concerns in tangible ways. He stated that “it is not a bilateral issue between the United States and Turkey and it’s not going to turn into one,” while also expressing confidence that the process will come to a successful conclusion soon.[82]

When various media outlets began reporting in January 2023 that the Administration has provided informal notification of a possible F-16 sale to Turkey (see “Congressional Notification Process” below), the Wall Street Journal cited unnamed U.S. officials predicting that congressional approval of the sale would be tied to Turkish ratification of Sweden’s and Finland’s NATO accession.[83] The same article cited the U.S. officials as saying that they are encouraging President Erdogan to stop delaying the accession.[84] Shortly thereafter, Turkish presidential adviser Ibrahim Kalin said that Turkey would only be in a position to ratify Sweden’s accession after it passed new anti-terror laws, a process he estimated would take about six months.[85] Erdogan then said publicly that he expects the extradition of “around 130” people before approving Turkish ratification.[86]

Syria[87] Background

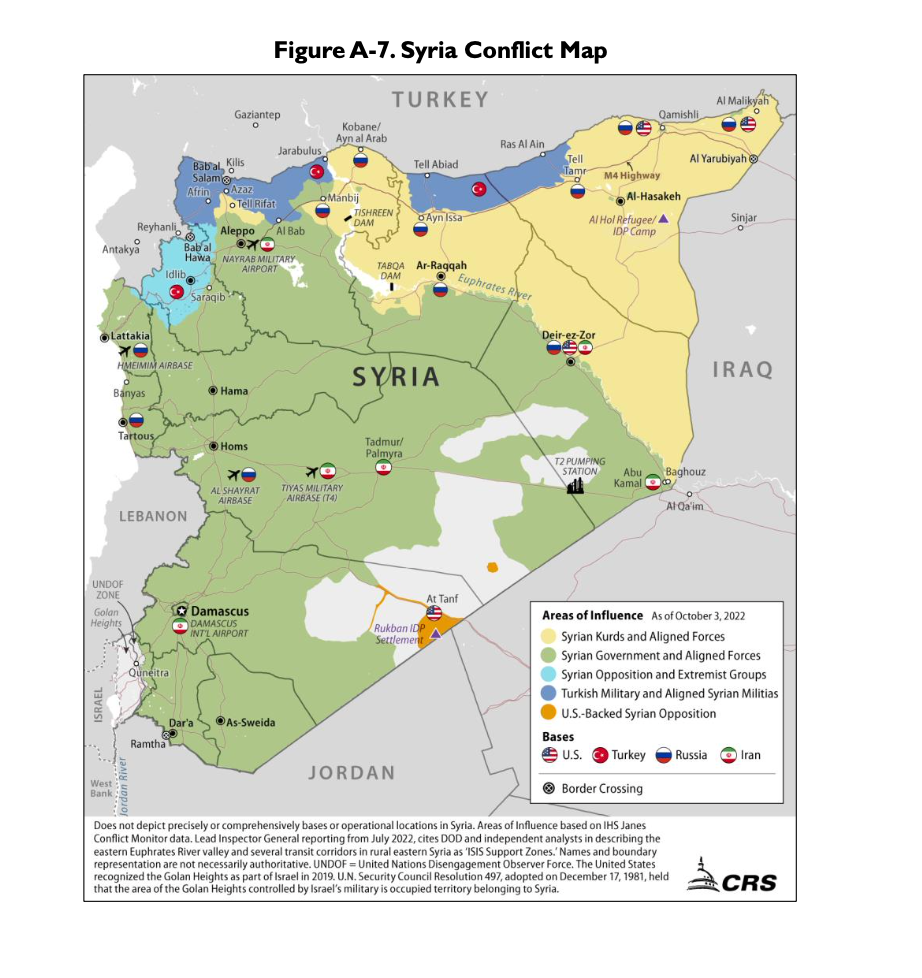

Turkey’s involvement in Syria’s conflict since it started in 2011 has been complicated and costly and has severely strained U.S.-Turkey ties.[88] Turkey’s priorities in Syria’s civil war have evolved during the course of the conflict. While Turkey still opposes Syrian President Bashar al Asad, it has engaged in a mix of coordination and competition with Russia and Iran (which support Asad) since intervening militarily in Syria starting in August 2016. Turkey and the United States have engaged in similarly inconsistent interactions in northern Syria east of the Euphrates River, where U.S. forces have been based.

Since at least 2014, Turkey has actively sought to thwart the Syrian Kurdish YPG from establishing an autonomous area along Syria’s northern border with Turkey. Turkey’s government considers the YPG and its political counterpart, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), to be a major threat to Turkish security, based on Turkish concerns that YPG/PYD gains have emboldened the PKK (which has links to the YPG/PYD) in its domestic conflict with Turkish authorities.[89] The YPG/PYD has a leading role within the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), an umbrella group including Arabs and other non-Kurdish elements that became the main U.S. ground force partner against the Islamic State in 2015. Turkish-led military operations in October 2019 to seize areas of northeastern Syria from the SDF—after U.S. Special Forces pulled back from the border area—led to major criticism of and proposed action against Turkey in Congress.[90] Turkey has set up local councils in areas of northern Syria that Turkey and Turkish-supported Syrian armed opposition groups—generally referred to under the moniker of the Syrian National Army (SNA)—have occupied since 2016 (see Figure A-7).

Erdogan has hinted at the possibility of repairing relations with Asad, after more than a decade in which Turkey has sought an end to Asad’s rule. As of early 2023, Russia is reportedly trying to broker better ties.[91] Turkey is seeking Syria’s help to push YPG fighters farther from the border and facilitate the return of Syrian refugees living in Turkey. Asad reportedly wants full Turkish withdrawal in return.[92] It is unclear whether the two leaders can compromise and how that would affect Turkey’s relationship with the SNA and the overall dynamic with other stakeholders in northern Syria. In response to a question about potential Turkey-Syria rapprochement, the State Department spokesperson has said that U.S. officials have told allies that now is not the time to normalize or upgrade relations with the Asad regime.[93]

Further Turkish Military Operations?

In May 2022, Erdogan began making public statements about a possible new Turkish military operation to expand areas of Turkish control in Syria as a means of countering YPG influence and providing areas for the voluntary return of Syrian refugees living in Turkey.[94] The presence of Syrian refugees has become politically charged in Turkey ahead of the scheduled 2023 elections, partly because of Turkey’s ongoing economic turmoil. In June testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Middle East Policy Dana Stroul said that any Turkish escalation in northern Syria “risks disrupting [Defeat]-ISIS operations,” including the security of SDF-managed detention facilities.[95] As of August 2022, a media report suggested that approximately 900 U.S. Special Forces personnel were deployed in northeastern Syria to help the SDF counter the Islamic State and to discourage other countries’ forces from occupying the area.[96]

A November 13, 2022, bombing that killed six people in Istanbul and injured dozens more may have boosted the Turkish government’s resolve to consider a military operation in Syria. Turkish officials have publicized information alleging YPG responsibility for the attack, though the YPG and PKK deny involvement.[97] Turkey began air and artillery strikes against SDF-controlled areas of northern Syria (including civilian infrastructure) and PKK targets in northern Iraq on November 20, 2022, dubbing the strikes Operation Claw-Sword and invoking self-defense as justification. Various U.S. official statements have acknowledged Turkey’s right to self-defense, but have generally opposed cross-border strikes and voiced concerns that Turkey-SDF clashes could reduce the SDF’s focus on countering the Islamic State.[98] In a November 30 call between Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin and Turkish Defense Minister Hulusi Akar, Secretary Austin expressed the Defense Department’s “strong opposition to a new Turkish military operation.”[99]

U.S.-Turkey Arms Sales Issues

How Turkey procures key weapons systems is relevant to U.S. policy in part because it affects Turkey’s partnerships with major powers and the country’s role within NATO. For decades, Turkey has relied on certain U.S.-origin equipment such as aircraft, helicopters, missiles, and other munitions to maintain military strength.[100]

Russian S-400 Acquisition: Removal from F-35 Program,

U.S. Sanctions, and Informal Holds

Turkey’s acquisition of the Russian S-400 system, which Turkey ordered in 2017 and Russia delivered in 2019,[101] has significant implications for Turkey’s relations with Russia, the United States, and other NATO countries. As a direct result of the transaction, the Trump Administration removed Turkey from the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program in July 2019, and imposed sanctions under the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA, P.L. 115-44) on Turkey’s defense procurement agency in December 2020.[102] In explaining the U.S. decision to remove Turkey from the F-35 program in 2019, the Defense Department rejected the idea of Turkey fielding a Russian intelligence collection platform (housed within the S-400) that could detect the stealth capabilities of F-35s in Turkey.[103] Additionally, Section 1245 of the FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA, P.L. 116-92) prohibits the use of U.S. funds to transfer F-35s to Turkey unless the Secretaries of Defense and State certify that Turkey no longer possesses the S-400. Turkey has conducted some testing of the S-400 but does not appear to have made the system generally operational. Turkey may need to forgo possession or use of the S-400 in order to have CAATSA sanctions removed.

An August 2020 article reported that some Members of congressional committees placed holds on major new U.S.-origin arms sales to Turkey in connection with the S-400 transaction. Customary practice allows some Members of Congress to place holds on major arms sales, though the holds are not legally binding.[104] Such a disruption to U.S. defense transactions with Turkey had not occurred since the 1975-1978 embargo over Cyprus.[105]

Possible F-16 Sales and Congressional Views Background (Including Turkey-Greece Issues)

In the fall of 2021, Turkish officials stated that they had requested to purchase 40 new F-16 fighter aircraft from the United States and to upgrade 80 F-16s from Turkey’s aging fleet. President Biden reportedly discussed the F-16 request with Erdogan during an October 2021 G20 meeting in Rome, indicating that the request would go through the regular arms sales consultation and notification process with Congress.[106] In November 2021, a Turkish defense expert described what upgrades of Turkey’s F-16 aircraft to the Block 70/72 Viper configuration could entail, including a new radar, other software and hardware enhancements, and structural improvements that significantly extend each aircraft’s service life.[107] Other countries that may receive new or upgraded F-16 Block 70/72 Vipers include Greece, Taiwan, Singapore, South Korea, Morocco, Bahrain, Bulgaria, the Philippines, and Slovakia.[108]

After Russia’s early 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Turkey’s value as a NATO ally amid a crisis implicating European security may have subsequently boosted the Administration’s interest in moving forward with an F-16 transaction with Turkey in early 2022. Responding to criticism of a possible F-16 sale from 53 Members of Congress in a February 2022 letter,[109] a State Department official wrote in March that Turkey’s support for Ukraine was “an important deterrent to malign influence in the region.”[110] While acknowledging that any sale would require congressional notification, the official added, “The Administration believes that there are nonetheless compelling long-term NATO alliance unity and capability interests, as well as U.S. national security, economic and commercial interests that are supported by appropriate U.S. defense trade ties with Turkey.”[111]

U.S. sales to boost the capabilities and extend the lifespan of Turkey’s F-16 fleet would provide Turkey time to develop its long-planned indigenous fifth-generation fighter aircraft, dubbed the TF-X and expected to come into operation over the next decade. Turkey is apparently seeking to partner with the United Kingdom (including companies BAE Systems and Rolls-Royce) to develop technology for the TF-X.[112] If unable to procure F-16s or F-16 upgrades to boost the Turkish air force’s capabilities during the transition to the TF-X, Turkish officials have hinted that they might consider purchasing Russian Su-35 fighter aircraft or Western European alternatives.[113] According to some defense analysts, however, Turkey’s calculus has likely changed after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.[114] One has written that if Turkey cannot procure F- 16s, “Security needs and politics dictate Ankara to remain within the NATO scope in its fighter jet inventory. The only viable options before Turkey flies the TF-X are the [Eurofighter] Typhoon, Saab [Gripen] and F-16 Block 70.”[115]

At the end of the June 2022 NATO summit in Spain, where Turkey agreed to allow the Sweden- Finland accession process to move forward (pending final Turkish ratification) and President Biden met with President Erdogan, Biden expressed support for selling new F-16s to Turkey as well as for upgrades. He also voiced confidence in obtaining congressional support.[116] However, Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Menendez has expressed disapproval due to what he has termed Erdogan’s “abuses across the region.”[117]

In addition to ongoing U.S.-Turkey tensions regarding Syrian Kurdish groups in northern Syria, Turkey-Greece disputes regarding overflights of contested areas and other longstanding Aegean Sea issues (referenced in the text box below) spiked in 2022 and attracted close congressional attention.[118] Erdogan announced in May 2022 that he would no longer deal with Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, after Mitsotakis appeared to raise concern about U.S.-Turkey arms transactions while addressing a May 17 joint session of Congress.[119] In December, the final version of the FY2023 NDAA (P.L. 117-263) excluded a House-passed condition on F-16 sales to Turkey (Section 1271 of H.R. 7900) related to potential overflights of Greek territory. However, the joint explanatory statement accompanying the NDAA included a provision stating, “We believe that North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) allies should not conduct unauthorized territorial overflights of another NATO ally’s airspace.”[120]

With U.S. officials already having notified a possible upgrade of F-16s for Greece to Congress in 2021,[121] U.S. decisions on bolstering Turkey’s F-16 fleet could have significant implications for the security balance between Turkey and Greece, and for relations involving the three countries.[122] In the past three years, Greece has strengthened its defense cooperation and relations with the United States and a number of regional countries such as France, Israel, and Egypt.[123] Enhanced U.S.-Greece defense cooperation has included an expanded U.S. military presence and increased U.S.-Greece and NATO military activities at Greek installations (see also text box below).[124]

Turkey-Greece-Cyprus Tensions: Background and Some Ongoing Issues[125]

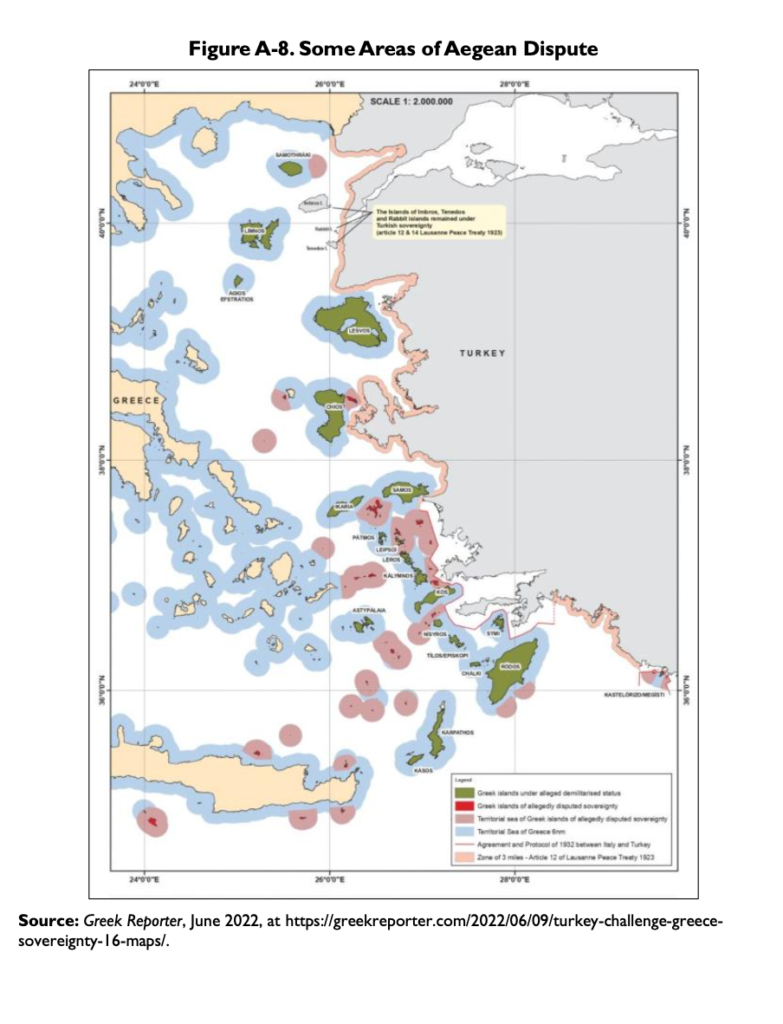

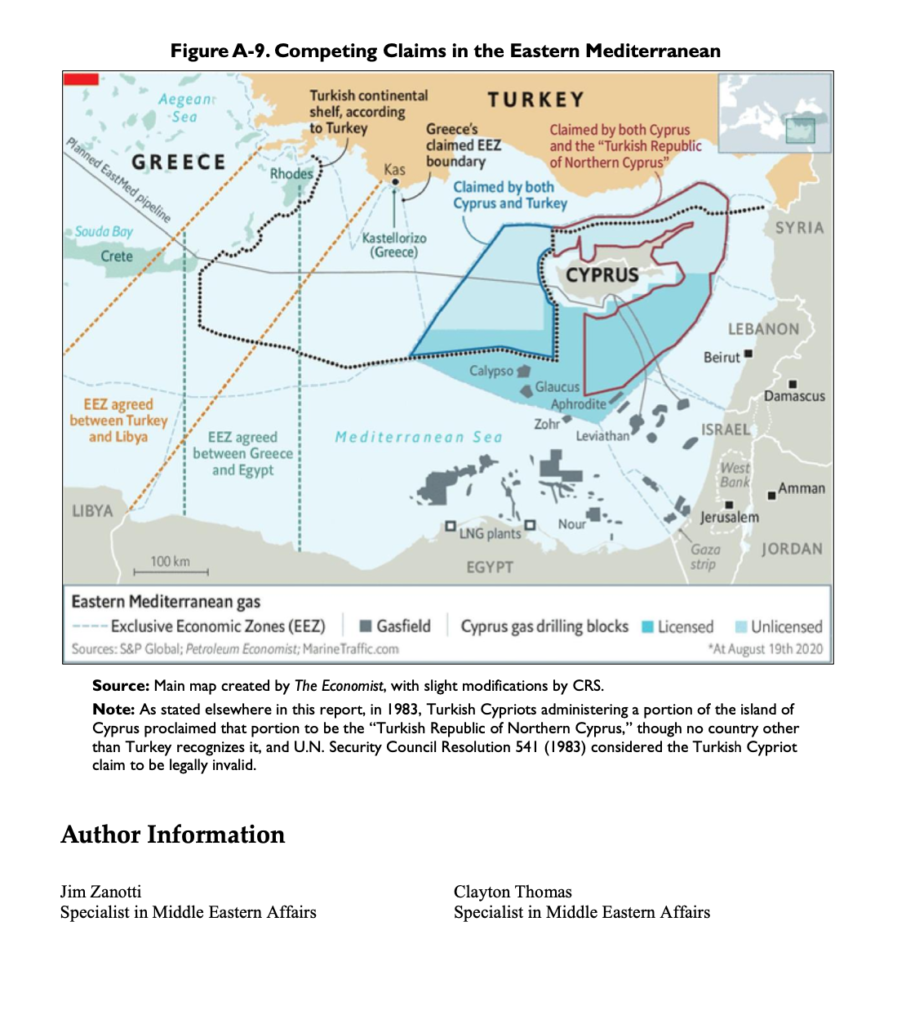

Since the 1970s, disputes between Greece and Turkey over territorial rights in the Aegean Sea and broader Eastern Mediterranean have been a major point of contention, bringing the sides close to military conflict on several occasions. The disputes, which have their roots in territorial changes after World War I, revolve around contested borders involving the two countries’ territorial waters, national airspace, exclusive economic zones (including energy claims), islands (and their use for military purposes), and continental shelves (see Figure A-8 and Figure A-9 for maps of some of the areas in dispute).

These tensions are related to and further complicated by one of the region’s major unresolved conflicts, the de facto political division of Cyprus along ethnic lines that dates from the 1974 military clash in which Turkish forces invaded parts of the island to prevent the ethnic Greek leadership from unifying Cyprus with Greece. The internationally recognized Republic of Cyprus (sometimes referred to as Cyprus), which has close ties to Greece, claims jurisdiction over the entire island, but its effective administrative control is limited to the southern two- thirds, where Greek Cypriots comprise a majority. Turkish Cypriots administer the northern one-third and are backed by Turkey, including a Turkish military contingent there since the 1974 clash.[126] In 1983, Turkish Cypriot leaders proclaimed this part of the island the “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus,” although no country other than Turkey recognizes it, and U.N. Security Council Resolution 541 (1983) considered the Turkish Cypriot claim to be legally invalid.

Turkish officials have complained about a significant new U.S. military presence at the Greek port of Alexandroupoli (alt. Alexandroupolis), located around 10-15 miles from the Turkish border.[127] U.S. officials have explained that they are using the port as a transit hub to send equipment to allies and partners in the region as part of a broader NATO response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.[128] In the March 2022 congressional hearing testimony mentioned above, Alan Makovsky said that having facilities at Alexandroupoli allows NATO to bypass logjams or closures of the Straits to transport troops and materiel overland to allies and partners.[129] After Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu said in October 2022 that the United States no longer maintains a balanced approach in the Aegean,[130] U.S. Ambassador to Turkey Jeff Flake released a statement saying that there has been no shift in U.S. security posture to favor Turkey or Greece, and that the NATO allies’ collective efforts are focused on ending Russia’s war in Ukraine.[131]

Congressional Notification Process

Various media sources—citing unnamed U.S. officials—reported in mid-January 2023 that the Administration has provided informal notifications to Congress about possible F-16 sales for Turkey and possible sales of up to 40 F-35 Joint Strike Fighters to Greece. According to these reports, the January informal notification on Turkey is for 40 new F-16s and 79 F-16 upgrade packages, along with 900 air-to-air missiles and 800 bombs, at an estimated total value of $20 billion.[132] Official confirmation may be unavailable because the State Department says it does not comment on possible arms sales until the executive branch formally notifies the sale to Congress.[133]

Formal notification of a possible arms sale to Congress generally occurs 20 to 40 days after informal notification, giving foreign affairs committees the opportunity during the interim to address concerns with the Administration in a confidential process. Formal notification generally does not proceed if a Member (usually a committee chair or ranking member) places a hold on the proposed transaction.[134] In the case of the proposed F-16 sale to Turkey, Al-Monitor wrote in mid-January to expect a “drawn-out process of briefings and deliberations on Capitol Hill before the sale moves forward.”[135] Citing unnamed U.S. officials, the Wall Street Journal reported (as also stated above) that congressional approval is contingent on Turkey’s ratification of Swedish- Finnish NATO accession.[136]

The Administration’s reported informal notifications of potential sales to Turkey and Greece come amid ongoing tensions between the two countries over maritime boundaries and U.S. regional involvement (as mentioned above).[137] By timing the informal notification on F-35s for Greece close to the notification for F-16s to Turkey, the Administration may be seeking to reassure Greek leaders and popular opinion that the United States is not favoring Turkey over Greece.[138] One journalist has argued:

A Greek acquisition of F-35s—coupled with the ongoing procurement of two dozen 4.5- generation Dassault Rafale F3R fighters from France and the upgrade of the bulk of its F- 16 fleet to the most advanced Block 72 configuration—will give the Hellenic Air Force a technological edge over its much larger Turkish counterpart. That will remain the case even if Turkey secures this F-16 deal.[139]

In response to the news of a possible F-35 sale to Greece, Turkish Foreign Minister Cavusoglu called on the United States to “pay attention” to the balance of power in the region.[140]

Shortly after the reported informal notifications, the New York Times cited Chairman Menendez as welcoming the F-35 sale to Greece while strongly opposing the F-16 sale to Turkey, saying:

President Erdogan continues to undermine international law, disregard human rights and democratic norms, and engage in alarming and destabilizing behavior in Turkey and against neighboring NATO allies. Until Erdogan ceases his threats, improves his human rights record at home—including by releasing journalists and political opposition—and begins to act like a trusted ally should, I will not approve this sale.[141]

As mentioned above, congressional holds on proposed arms sales are not legally binding, but the executive branch generally gives broad deference to the chair and ranking member of the foreign affairs committees on possible major foreign arms sales. After formal notification of a potential sale, any Member of Congress can privilege a joint resolution of disapproval for floor action if the Member introduces it within the time period prescribed under the Arms Export Control Act (P.L. 90-629, 82 Stat. 1320).[142 For NATO allies such as Turkey and Greece, the prescribed time period is 15 days after formal notification.[143] The President can veto a resolution of disapproval, subject to congressional override.

Appendix. Maps, Facts, and Figures

1 In late 2021, President Erdogan directed the use of “Türkiye” (the country’s name in Turkish) in place of “Turkey” or other equivalents (e.g., the German “Türkei,” the French “Turquie”) in Turkish government documents and communications. In June 2022, the United Nations accepted the Turkish request to change the country’s name at the body to “Türkiye.” In January 2023, the State Department spokesperson said that the department would use the revised spelling “in most formal diplomatic and bilateral contexts” where appropriate. The Board on Geographic Names retained both “Turkey” and “Republic of Turkey” as conventional names, and the spokesperson said that the State Department could use those names if it is in furtherance of broader public understanding. State Department Press Briefing, January 5, 2023.

2 State Department, “Secretary Antony J. Blinken and Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu Before Their Meeting,” January 18, 2023; State Department Press Briefing, January 18, 2023.

3 Alper Coskun, “Making the New U.S.-Turkey Strategic Mechanism Meaningful,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, May 12, 2022; Kali Robinson, “Turkey’s Growing Foreign Policy Ambitions,” Council on Foreign Relations, August 24, 2022.

4 Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), Limited Referendum Observation Mission Final Report, Turkey, April 16, 2017 (published June 22, 2017); OSCE, International Election Observation Mission, Statement of Preliminary Findings and Conclusions, Turkey, Early Presidential and Parliamentary Elections, June 24, 2018 (published June 25, 2018).

5 Kemal Kirisci and Berk Esen, “Might the Turkish Electorate Be Ready to Say Goodbye to Erdoğan After Two Decades in Power?” Just Security, November 22, 2021.

6 State Department, Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2021, Turkey; Turkey; European Commission, Turkiye 2022 Report, October 6, 2022.

7 Gareth Jenkins, “Five Years After July 15: Erdogan’s New Turkey and the Myth of Its Immaculate Conception,” Turkey Analyst, July 15, 2021; “Turkey coup: Top officers given life terms in mass trial,” BBC News, April 7, 2021.

8 Berkay Mandiraci, “Turkey’s PKK Conflict: A Regional Battleground in Flux,” International Crisis Group, February 18, 2022.

9 Nektaria Stamouli, “Turkey’s inflation drops sharply in boost for Erdoğan,” Politico, January 3, 2023; Beril Akman, “Turkey slashes interest rate in line with Erdogan’s demand,” Bloomberg, November 24, 2022; “Yearly inflation in Turkey rises to new 24-year high of 85%,” Associated Press, November 3, 2022

10 Mustafa Sonmez, “Turkish inflation hits 85.5% as doubts linger over official data,” Al-Monitor, November 3, 2022.

11 Baris Balci and Inci Ozbek, “Turkey Rewrites All Inflation Forecasts but Won’t Budge on Rates,” Bloomberg, April 28, 2022.

12 Mikolaj Rogalewicz, “Economic crisis in Turkey,” Warsaw Institute Review, April 25, 2022.

13 “EXPLAINER: Turkey’s Currency Is Crashing. What’s the Impact?” Associated Press, December 3, 2021; Carlotta Gall, “Keeping His Own Counsel on Turkey’s Economy,” New York Times, December 11, 2021.

14 “Turkey will keep lowering interest rates: Erdogan,” Daily Sabah, June 6, 2022; Mustafa Akyol, “How Erdogan’s Pseudoscience Is Ruining the Turkish Economy,” Cato Institute, December 3, 2021.

15 Ben Hubbard, “Skyrocketing Prices in Turkey Hurt Families and Tarnish Erdogan,” New York Times, December 5, 2022; Baris Balci and Inci Ozbek, “Turkey Rewrites All Inflation Forecasts,” Bloomberg, April 28, 2022.

16 Laura Pitel “Turkey finance minister defends economic links with Russia,” Financial Times, October 25, 2022; Murat Kubilay, “As liquidity problems worsen, Turkey turns to capital controls and informal FX flows,” Middle East Institute, November 7, 2022.

17 Erdogan may seek to have Turkey’s parliament (by a three-fifths vote) schedule early elections, because Turkey’s constitution requires that a president can only seek a third term if parliament (rather than the president) moves up the election date. Some Erdogan supporters argue that Erdogan’s next term would be his second under Turkey’s constitution because his first term (which was not a full five years) came before the current constitutional amendments regarding the presidency became effective in 2018. “Can Recep Tayyip Erdoğan run for a third term as president?” James in Turkey, last updated December 19, 2022.

18 “President Erdoğan hints at May 14 for general elections,” Hurriyet Daily News, January 18, 2023.

19 Hubbard, “Skyrocketing Prices in Turkey Hurt Families and Tarnish Erdogan”; “Polls indicate close race between rival blocs, yet people increasingly think Erdoğan will win,” BIA News, October 12, 2022; Berk Esen, “The opposition alliance in Turkey: A viable alternative to Erdogan?” SWP Comment, August 2022.

20 Ozgur Unluhisarcikli, “It Is Not Too Early to Think About Political Change in Turkey,” German Marshall Fund of the United States, January 10, 2022; Kirisci and Esen, “Might the Turkish Electorate Be Ready to Say Goodbye to Erdoğan After Two Decades in Power?”

21 Ozer Sencar of Metropoll, in Laura Pitel, “Will the ailing Turkish economy bring Erdogan down?” Financial Times, November 1, 2021.

22 Unnamed Western diplomat quoted in Laura Pitel, “Defeating Erdogan: Turkey’s opposition searches for a champion,” Financial Times, May 5, 2022.

23 Andrew Wilks, “Turkish opposition forms plan to oust Erdogan, restore parliament’s power,” Al-Monitor, February 15, 2022.

24 Ibid.; Pitel, “Defeating Erdogan.”

25 “Türkiye’s CHP forms technocratic committee to advise the govt,” Yetkin Report, December 4, 2022; Berk Esen, “Post-2023 election scenarios in Turkey,” SWP Comment, September 2022; Alper Coskun and Sinan Ulgen, “Political Change and Turkey’s Foreign Policy,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, November 2022.

26 Gonca Tokyol, “Wielding Istanbul’s clout, Kaftancioglu and the CHP take aim at 2023 elections,” Turkey recap (Substack), November 16, 2022.

27 “The opposition should win, but it has obstacles in its way,” Economist, January 16, 2023; James Ryan, “The path ahead in Turkey’s upcoming electoral campaign,” War on the Rocks, November 10, 2022.

28 “Turkish court orders jail, political ban for Erdogan rival,” Reuters, December 14, 2022; Andrew Wilks, “Cases against opposition politicians mount ahead of Turkish elections,” Al-Monitor, June 2, 2022.

29 Ben Hubbard and Safak Timur, “Conviction May Sideline Rival of Turkish Leader,” New York Times, December 15, 2022.

30 Ibid.; Yusuf Selman Inanc, “Turkey: Istanbul mayor given two-year jail sentence and ‘political ban,’” Middle East Eye, December 14, 2022.

31 State Department, “Turkey’s Conviction and Sentencing of Istanbul Mayor Ekrem Imamoglu,” December 15, 2022.

32 Amberin Zaman, “Istanbul mayor charged with corruption as Turkish opposition weighs Erdogan challenger,” Al- Monitor, January 11, 2023.

33 “Istanbul mayor, Erdogan critic faces fraud case – Haberturk,” Reuters, January 11, 2023.

34 Mesut Yegen, “Erdogan and the Turkish Opposition Revisit the Kurdish Question,” SWP Comment, April 2022.

35 Diego Cupolo, “Top Turkish court accepts revised indictment to ban pro-Kurdish party,” Al-Monitor, June 21, 2021.

36 Amberin Zaman, “Will Kurds’ choice to field own candidate benefit Erdogan or Turkey’s opposition?” Al-Monitor, January 9, 2023.

37 Andrew Wilks, “Turkey’s historic election could move up as Erdogan calculates,” Al-Monitor, January 5, 2023.

38 Salem Solomon, “Ethiopia Ups Use of Drone Strikes in Conflict Prompting Worries About Civilian Toll,” Voice of America, February 2, 2022; Fehim Tastekin, “Are Turkish drones complicating disputes in Central Asia?” Al-Monitor, September 26, 2022; Federico Borsari, “Turkey’s drone diplomacy: Lessons for Europe,” European Council on Foreign Relations, January 31, 2022; Alper Coskun, “Strengthening Turkish Policy on Drone Exports,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, January 18, 2022.

39 See, for example, Richard Outzen, “What Is Turkey Thinking in the Eastern Med?” Hoover Institution, December 7, 2021.

40 See CRS Report R41368, Turkey (Türkiye): Background and U.S. Relations, by Jim Zanotti and Clayton Thomas.

41 State Department, “Joint Statement on the Meeting of Secretary Blinken and Turkish Foreign Minister Cavusoglu,” May 18, 2022.

42 Nur Ozcan Erbay, “Ankara to use compartmentalization in managing relations,” Daily Sabah, June 24, 2021; Stephen J. Flanagan et al., Turkey’s Nationalist Course: Implications for the U.S.-Turkish Strategic Partnership and the U.S. Army, RAND Corporation, 2020.

43 Rich Outzen and Soner Cagaptay, “The Third Age of Erdoğan’s Foreign Policy,” Center for European Policy Analysis, February 17, 2022.

44 Alan Makovsky, “Turkey’s Hinge Election,” Jerusalem Strategic Tribune, November 2022; Coskun and Ulgen, “Political Change and Turkey’s Foreign Policy.”

45 Coskun and Ulgen, “Political Change and Turkey’s Foreign Policy.”

46 Dimitar Bechev, “Russia, Turkey and the Spectre of Regional Instability,” Al Sharq Strategic Research, April 13, 2022; Mitch Prothero, “Turkey’s Erdogan has been humiliating Putin all year,” Business Insider, October 22, 2020.

47 See, for example, Xander Snyder, “Beyond Incirlik,” Geopolitical Futures, April 19, 2019.

48 “Pentagon pushes back on claim that US to leave Turkey’s Incirlik base,” Al-Monitor, September 16, 2020; Joseph Trevithick, “Docs Show US to Massively Expand Footprint at Jordanian Air Base amid Spats with Turkey, Iraq,” The Drive, January 14, 2019.

49 Prepared testimony of Alan Makovsky, Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress, “Opportunities and Challenges in the Eastern Mediterranean: Examining U.S. Interests and Regional Cooperation,” House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on the Middle East, North Africa and Global Counterterrorism; and Subcommittee on Europe, Energy, the Environment and Cyber, March 31, 2022, available at https://www.americanprogress.org/article/opportunities-and- challenges-in-the-eastern-mediterranean-examining-u-s-interests-and-regional-cooperation/.

50 Can Kasapoglu, “Turkish Drone Strategy in the Black Sea Region and Beyond,” Jamestown Foundation, October 12, 2022; Jeffrey Mankoff, “As Russia Reels, Eurasia Roils,” War on the Rocks, October 11, 2022.

51 Saban Kardas, “The War in Ukraine and Turkey’s Cautious Counter-Balancing Against Russia,” German Marshall Fund of the United States, March 3, 2022.

52 “Turkey President Erdoğan on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the future of NATO,” PBS Newshour, September 19, 2022; “Turkey recognises Russia-Ukraine ‘war’, may block warships,” Agence France Presse, February 27, 2022.

53 For information on the MRAPs, see Burak Ege Bekdil, “Turkey sends 50 mine-resistant vehicles to Ukraine, with more expected,” Defense News, August 22, 2022.

54 Jack Detsch and Robbie Gramer, “Turkey Is Sending Cold War-Era Cluster Bombs to Ukraine,” Foreign Policy, January 10, 2023.

55 Ragip Soylu, “Russia-Ukraine war: Turkey denies supplying Kyiv with cluster munitions,” Middle East Eye, January 14, 2023.

56 For information on the Crimea invasion, see CRS Report R45008, Ukraine: Background, Conflict with Russia, and U.S. Policy, by Cory Welt.

57 Metin Gurcan, “Turkey-Ukraine defense industry ties are booming,” Al-Monitor, May 1, 2017.

58 “Turkey, Ukraine Sign Military Cooperation Agreements,” Associated Press, October 16, 2020; Christopher Isajiw, “Free trade and drones: Turkey and Ukraine strengthen strategic ties,” Atlantic Council, February 11, 2022.

59 Kasapoglu, “Turkish Drone Strategy in the Black Sea Region and Beyond.”

60 Ibid.

61 Dorian Jones, “Turkey Strengthens Defense Industry with Its Ukraine Partnership,” Voice of America, February 4, 2022.

62 David Hambling, “New Bayraktar Drones Still Seem to Be Reaching Ukraine,” Forbes, May 10, 2022. The TB2’s main producer, Baykar Technology, is planning to build a $100 million factory in Ukraine that could be in position within about three years to manufacture the full range of the company’s drones—doubling Baykar’s overall production capacity. Jared Malsin, “Erdogan Seizes Chance to Give Turkey a Global Role,” Wall Street Journal, November 7, 2022.

63 Kate Tringham, “Update: Turkey launches first Ada-class corvette for Ukraine and cuts steel for second,” Janes Navy International, October 3, 2022.

64 “Ukraine, Russia agree to export grain, ending a standoff that threatened food supply” Associated Press, July 22, 2022.

65 See https://www.un.org/en/black-sea-grain-initiative/background.

66 White House, “Readout of President Biden’s Meeting with President Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkiye,” November 15, 2022.

67 Patricia Cohen, “Turkey Tightens Energy Ties with Russia as Other Nations Step Back,” New York Times, December 10, 2022.

68 “Russia’s Putin, Turkey’s Erdogan agree to boost economic, energy cooperation,” Agence France Presse, August 5, 2022.

69 Amberin Zaman, “US deputy treasury secretary in Turkey to warn against evading Russian sanctions,” Al-Monitor, June 22, 2022.

70 Elif Ince et al., “Russian Superyachts, Subject to Sanctions, Find a Haven in Turkey,” New York Times, October 24, 2022.

71 For more information on Gulen and the movement, see archived CRS In Focus IF10444, Fethullah Gulen, Turkey, and the United States: A Reference, by Jim Zanotti and Clayton Thomas.

72 Semih Idiz, “How long can Erdogan sustain threat to veto Finnish, Swedish NATO bids?” Al-Monitor, May 17, 2022.

73 Sources citing links between the PKK and YPG (or PKK affiliates in Syria) include State Department, Country Reports on Terrorism 2020, Syria; Mandiraci, “Turkey’s PKK Conflict: A Regional Battleground in Flux”; Barak Barfi, Ascent of the PYD and the SDF, Washington Institute for Near East Policy, April 2016.

74 Agreement text available at Twitter, Ragip Soylu, June 28, 2022 – 2:48 PM, at https://twitter.com/ragipsoylu/status/ 1541856195257966592.

75 Amberin Zaman, “Erdogan says Sweden’s, Finland’s NATO memberships not done deal,” Al-Monitor, June 30, 2022.

76 William Mauldin and Michael R. Gordon, “Sweden and Finland on Track for NATO Membership,” Wall Street Journal, December 9, 2022.

77 See footnote 74.

78 “Sweden deports man with alleged ties to Kurdish militant group,” Reuters, December 3, 2022.

79 “Swedish court blocks extradition of journalist sought by Turkey in Nato deal,” Agence France Presse, December 19, 2022.

80 Steven Erlanger, “Sweden Says Turkey Terms on NATO Bid Go Too Far,” New York Times, January 10, 2023; Ben Keith, “Turkey’s Erdoğan Deploys Sweden and Finland’s NATO Membership Bids to Further His Repression,” Just Security, October 28, 2022.

81 Remi Banet, “Erdogan announces new meeting on Sweden’s NATO bid,” Agence France Presse, November 8, 2022.

82 State Department, “Secretary Antony J. Blinken with Swedish Foreign Minister Tobias Billström and Finnish Foreign Minister Pekka Haavisto at a Joint Press Availability,” December 8, 2022.

83 Jared Malsin and Vivian Salama, “Biden Administration to Ask Congress to Approve F-16 Sale to Turkey,” Wall Street Journal, January 13, 2023.

84 Ibid.

85 “Turkey ‘Not In A Position’ To Ratify Swedish NATO Bid,” Agence France Presse, January 14, 2023.

86 “Sweden, Finland must send up to 130 ‘terrorists’ to Turkey for NATO bid, Erdogan says,” Reuters, January 16, 2023.

87 See CRS Report RL33487, Armed Conflict in Syria: Overview and U.S. Response, coordinated by Carla E. Humud.

88 For background, see Burak Kadercan, “Making Sense of Turkey’s Syria Strategy: A ‘Turkish Tragedy’ in the Making,” War on the Rocks, August 4, 2017.

89 See, for example, Soner Cagaptay, “U.S. Safe Zone Deal Can Help Turkey Come to Terms with the PKK and YPG,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, August 7, 2019. For sources linking the PKK to the YPG (or PKK affiliates in Syria), see footnote 73.

90 Rachel Oswald, “Sanctions on Turkey go front and center as Congress returns,” Roll Call, October 15, 2019.

91 Fehim Tastekin, “Fledgling Turkish-Syrian dialogue faces bumpy road ahead,” Al-Monitor, January 14, 2023.

92 “Syria resisting Russia’s efforts to broker Turkey summit, sources say,” Reuters, December 5, 2022.

93 State Department Press Briefing, January 3, 2023.

94 Fehim Tastekin, “The stumbling blocks facing Turkey’s new operation plan in Syria,” Al-Monitor, May 30, 2022.

95 Statement of Dana Stroul, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Middle East Policy, Testimony Before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, “The Path Forward on U.S.-Syria Policy: Strategy and Accountability,” June 8, 2022, available at https://www.foreign.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/060822_%20Stroul_Testimony.pdf.

96 Alexander Ward et al., “What are we still doing in Syria?” Politico, August 26, 2022.

97 “Turkey blames deadly bomb on Kurdish militants; PKK denies involvement,” Reuters, November 14, 2022.

98 Ibid.

99 Defense Department, “Readout of Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III’s Phone Call With Turkish Minister of National Defense Hulusi Akar,” November 30, 2022.

100 Turkey also has procurement and co-development relationships with other NATO allies, including Germany (submarines), Italy (helicopters and reconnaissance satellites), and the United Kingdom (a fighter aircraft prototype).

101 “Turkey, Russia sign deal on supply of S-400 missiles,” Reuters, December 29, 2017. According to this source, Turkey and Russia reached agreement on the sale of at least one S-400 system for $2.5 billion, with the possibility of a second system to come later.

102 Archived CRS Insight IN11557, Turkey: U.S. Sanctions Under the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA), by Jim Zanotti and Clayton Thomas.

103 Defense Department, “Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment Ellen M. Lord and Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Policy David J. Trachtenberg Press Briefing on DOD’s Response to Turkey Accepting Delivery of the Russian S-400 Air and Missile Defense System,” July 17, 2019.

104 CRS Report RL31675, Arms Sales: Congressional Review Process, by Paul K. Kerr.

105 Valerie Insinna et al., “Congress has secretly blocked US arms sales to Turkey for nearly two years,” Defense News, August 12, 2020.

106 “Biden talks F-16s, raises human rights in meeting with Turkey’s Erdogan,” Reuters, October 31, 2021; Diego Cupolo, “In troubled US-Turkey relations, F-16 deal seen as path for dialogue,” Al-Monitor, November 1, 2021. For background information, see CRS Report RL31675, Arms Sales: Congressional Review Process, by Paul K. Kerr.

107 Arda Mevlutoglu, “F-16Vs Instead of F-35s: What’s behind Turkey’s Request?” Politics Today, November 22, 2021.

108 Ibid.

109 Text of letter available at https://pallone.house.gov/sites/pallone.house.gov/files/ 20220123%20Letter%20on%20Turkey%20F-16%20Request.pdf.

110 Acting Assistant Secretary of State for Legislative Affairs Naz Durakoglu, quoted in Humeyra Pamuk, “U.S. says potential F-16 sale to Turkey would serve U.S. interests, NATO – letter,” Reuters, April 6, 2022.

111 Ibid.

112 Burak Ege Bekdil, “Russian invasion of Ukraine is reviving Euro-Turkish fighter efforts,” Defense News, March 9, 2022.

113 “Türkiye signals it may turn to Russia if US blocks F-16 jet sales,” Daily Sabah, September 9, 2022; Paul Iddon, “Here Are Turkey’s Stopgap Options Until It Can Acquire Fifth-Generation Fighters,” Forbes, March 15, 2021.

114 Paul Iddon, “Where can Turkey buy fighter jets if US F-16 deal falls through?” Middle East Eye, September 29, 2022.

115 Bekdil, “Russian invasion of Ukraine is reviving Euro-Turkish fighter efforts.”

116 “Biden supports F-16 sale to Turkey, is confident about congressional approval,” Reuters, June 30, 2022.

117 Twitter, Senate Foreign Relations Committee, December 7, 2022 – 10:57 AM, at https://twitter.com/SFRCdems/ status/1600519759493304321.

118 Alexis Heraclides, “The unresolved Aegean dispute: Problems and prospects,” Greece and Turkey in Conflict and Cooperation, New York: Routledge, 2019, pp. 89-108; Ryan Gingeras, “Dogfight over the Aegean: Turkish-Greek Relations in Light of Ukraine,” War on the Rocks, June 8, 2022.

119 Greek Prime Minister’s website, “Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis’ address to the Joint Session of the U.S. Congress,” May 17, 2022.

120 Joint explanatory statement available at https://rules.house.gov/sites/democrats.rules.house.gov/files/BILLS- 117HR7776EAS-RCP117-70-JES.pdf.

121 Defense Security Cooperation Agency, “Greece – F-16 Sustainment Materiel and Services, Transmittal No. 21-49,” August 3, 2021.

122 Aaron Stein, “You Go to War with the Turkey You Have, Not the Turkey You Want,” War on the Rocks, May 30, 2022.

123 See CRS Report R41368, Turkey (Türkiye): Background and U.S. Relations, by Jim Zanotti and Clayton Thomas.

124 State Department, “U.S. Security Cooperation with Greece,” October 31, 2022.

125 See CRS Report R41368, Turkey (Türkiye): Background and U.S. Relations, by Jim Zanotti and Clayton Thomas.

126 Turkey retains between 30,000 and 40,000 troops on the island (supplemented by several thousand Turkish Cypriot soldiers). This presence is countered by a Greek Cypriot force of approximately 12,000 with reported access to between 50,000 and 75,000 reserves. “Cyprus – Army,” Janes Sentinel Security Assessment – Eastern Mediterranean, February 3, 2021. The United Nations maintains a peacekeeping mission (UNFICYP) of approximately 900 personnel within a buffer zone headquartered in Cyprus’s divided capital of Nicosia. The United Kingdom maintains approximately 3,000 personnel at two sovereign base areas on the southern portion of the island at Akrotiri and Dhekelia.

127 Niki Kitsantonis and Anatoly Kurmanaev, “Sleepy Greek Port Turns into Pivotal Transit Point for American Military,” New York Times, August 19, 2022.

128 Ibid.; Department of Defense News, “Strategic Port Access Aids Support to Ukraine, Austin Tells Greek Defense Minister,” July 18, 2022.

129 Prepared testimony of Alan Makovsky, “Opportunities and Challenges in the Eastern Mediterranean: Examining U.S. Interests and Regional Cooperation.”

130 “Cavusoglu says US siding against Turkey in the Aegean, East Med,” Kathimerini, October 21, 2022.

131 Twitter, U.S. Embassy Türkiye, October 18, 2022 – 3:32 AM, at https://twitter.com/USEmbassyTurkey/status/1582273449145212928.

132 “US working with Congress towards Turkey F-16 sale,” Al-Monitor, January 13, 2023; Malsin and Salama, “Biden Administration to Ask Congress to Approve F-16 Sale to Turkey”; Michael Crowley and Edward Wong, “U.S. Plan to Sell Fighter Jets to Turkey Is Met with Opposition,” New York Times, January 14, 2023.

133 State Department Press Briefing, January 13, 2023.

134 CRS Report RL31675, Arms Sales: Congressional Review Process, by Paul K. Kerr.

135 “US working with Congress towards Turkey F-16 sale.”

136 Malsin and Salama, “Biden Administration to Ask Congress to Approve F-16 Sale to Turkey.”

137 CRS Report R41368, Turkey (Türkiye): Background and U.S. Relations, by Jim Zanotti and Clayton Thomas.

138 Malsin and Salama, “Biden Administration to Ask Congress to Approve F-16 Sale to Turkey”; Crowley and Wong, “U.S. Plan to Sell Fighter Jets to Turkey Is Met with Opposition.”

139 Paul Iddon, “Balance of Power: Why the Biden Administration Wants to Sell Turkey F-16s and Greece F-35s,” Forbes, January 16, 2023.

140 Andrew Wilks, “Turkish FM travels to Washington seeking to seal deal for F-16 fighter jets,” Al-Monitor, January 17, 2023.

141 Crowley and Wong, “U.S. Plan to Sell Fighter Jets to Turkey Is Met with Opposition.” Alexander Ward et al., “Menendez vows to block plan to sell fighter jets to Turkey,” Politico, January 13, 2023.

142 For historical background on how the congressional review process has affected some U.S. arms sales, see CRS Report R44984, Arms Sales in the Middle East: Trends and Analytical Perspectives for U.S. Policy, coordinated by Clayton Thomas; and archived CRS Report R46580, Israel’s Qualitative Military Edge and Possible U.S. Arms Sales to the United Arab Emirates, coordinated by Jeremy M. Sharp and Jim Zanotti.

143 CRS Report RL31675, Arms Sales: Congressional Review Process, by Paul K. Kerr.

Author Information

Jim Zanotti, Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs

Clayton Thomas, Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs