Ayşan Sönmez, Paris 8 University – IFG, Ph.D. Candidate

Kitty Felde, an award-winning public radio journalist and playwright, wrote a play titled A Patch of Earth in 2007 which was based on the real-life story of Drazen Erdemovic, who was put on trial at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in 1996. As a journalist, she followed his case and wrote the play based on the trial testimony from actual transcripts. The play tells the story of a twenty-four year-old Croat soldier who pled guilty to war crimes he committed during the Srebrenica massacre along with Serbian troops. As he was the first person to be sentenced by the International War Crimes Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, Felde focuses on the issue of justice in terms of both the legal systems that were put into place and the personal and ethical responsibilities of soldiers who were ordered to participate in acts of mass murder. The play takes its name from a central question: How much blood can a piece of earth absorb before it reaches the saturation point? (Felde 2007, p. 14) As such, the play carries a symbolic meaning that deals with a pressing concern: When is it possible for wars and deaths to come to an end? And, at what point can we stop those deaths? She asked that question with the aim of finding a peaceful means of resolution by drawing attention to the importance of conscientious inquiries. Her play invites readers and audiences to resist the wars that people wage in an age when war crimes are generally seen as international bargaining chips and have the potential to be co-opted by international politics.

Kitty Felde (Image: kittyfelde.com)

Drazen Erdemovic, who was the Bosnian-Serb defendant at the center of the trial that Kitty Felde was following and the protagonist of the play she wrote, was a mercenary who participated in the war as a member of the 10th Sabotage Detachment of the Army of the Serbian Republic.[1] He revealed to the press details concerning what happened in the 1996 Srebrenica massacre and confessed to the crimes he committed in that clandestine ethnic cleansing operation, as a consequence of which about 8,000 Bosnians were killed on a farm in the village of Pilica. As a gunman, he was personally involved in the killing of 70-120 people during the course of the massacre. After admitting his guilt to the French daily, “Le Figaro”, Drazen’s case was transferred to the war crimes court. He was found guilty of committing crimes against humanity and violating the laws and customs of war, for which he was sentenced to ten years in prison. However, as the appeals court ruled in his favor, his sentence was reduced to five years, and then he was released in exchange for the testimony he provided against General Karadzic, one of the primary figures responsible for the killings that took place (Institute for War & Peace Reporting 2012).

Throughout the play, Drazen finds himself caught between his conscience and those attitudes that society deems to be « correct. » Drazen, who was twenty-four years old at the time of the event, did not eagerly choose to serve in the military, and he had no previous military training. During the war, he was involved for a while in the smuggling of people across the border, and after the police caught him, he took on temporary jobs but he wasn’t able to make ends meet. Ultimately, he threw in his lot with the army, which he saw as being « trustworthy, » and became a mercenary. Initially, he claims to have refused to kill anyone as events unfolded, but in the end he was given two options: kill or be killed, and he chose to kill.

Although Drazen is of Croatian descent, he is married to a Serbian woman, and his father is a staunch Tito sympathizer. When he returns from the war, his wife, father, mother, and former comrades ask him to « keep quiet » and go on in life with his son and family. However, the ghosts of the Bosnians he and his fellow soldiers killed in Srebrenica haunt him throughout the play. Felde built up the plot on the basis of flashbacks which frequently interrupt the main narrative of the play, which is set at the court of the International War Crimes Tribunal. Audiences learn about Drazen’s past by way of those flashbacks, including his enlistment in the army, interactions with his family, and encounters with the ghosts of the Srebrenica victims. While the storyline often circles back to the court, by means of flashbacks we see Drazen languishing in his prison cell, chatting with his family, arguing with his fellow soldiers in the 10th Sabotage Detachment, and trying to explain himself to his wife and child. As Drazen drifts further from his conscience, ghosts start to appear and they remind him of the massacre (only Drazen and his young son, however, can see the ghosts). Many of the people around him, especially his wife, claim that he is merely « dreaming, » and with the exception of his ex-girlfriend and members of the press, they try to persuade him to « forget everything » that happened (Felde 2008; kittyfelde.com).

(Image : Getty Images)

Through analyses of the text of Kitty Felde’s A Patch of Earth, we can make a number of observations about the « implied » and « possible » causes of war crimes as well as the measures that can be taken to prevent them.

The main arguments that can be drawn from A Patch of Earth are as follows:

1. As crimes committed in the past go unpunished, they impose burdens on future generations and create new conditions for the emergence of impunity;

2. Societal pressure prevents such crimes from being exposed; and,

3. International courts and organizations seek out reconciliation as a means of striking a balance among international powers, but they are not so interested in ensuring that justice prevails.

Before focusing on the content in which these three arguments are situated, it will be helpful to delve into the background of the Srebrenica massacre as it constitutes the underlying plot of the play.

War crimes in Srebrenica – basic facts [2]

The Srebrenica massacre was one of the numerous ethnic cleansing operations carried out in the Yugoslavian Civil War, which lasted from 1991 to 1995. It was perpetrated by units of the Serbian Republic of Bosnia army under the command of General Ratko Mladic, supported by a Serbian paramilitary unit (the Scorpions) to create an « ethnically pure » territory and to join the region to Serbia. This was the plan for creating a « Greater Serbia, » an ideology that appeared back in the 1840s. More than 8,000 Bosnian men and teenagers were murdered in Srebrenica, Bosnia, and Herzegovina in July 1995 during the wider Bosnian War.

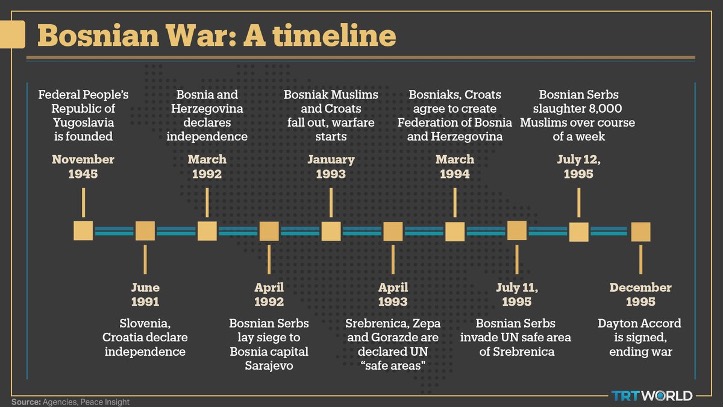

The Bosnian War (1992 – 1995) began due to the collapse of the former Yugoslavia, which was made up of six republics: Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Slovenia, Montenegro, and Macedonia. By the 1990s, along with the severe economic deterioration covering the country as a whole, the Bosnian Croats, Bosnian Muslims, and Bosnian Serbs all wanted to control the territory of Herzegovina and Bosnia for their countries. While the European Union did recognize the independence of Slovenia and Croatia, it also invited Bosnia and Herzegovina for the application to recognize their independence. Catholic Croats and Orthodox Serbs occupied Socialist Bosnia on February 29, 1992, and following this, Bosnian Muslims decided to hold an independence referendum. In March 1992, Herzegovina and Bosnia declared independence. Bosnian Serbs’ political representatives boycotted the referendum, and eventually, within the escalating political conflict, the Bosnian Serbs laid a siege to Bosnian capital Sarajevo in April 1992, prominently targeting the Muslims. Bosnian Muslims and Bosnian Croats lost their power against Bosnian Serbs after the siege for 47 months. In January 1993, the Bosnian Serbs attacked the Croatian civilians and Bosnian Muslim civilians in regions under their administration. Thousands of Bosnian Muslims from the surrounding areas sought refuge in Srebrenica, fleeing Bosnian Serb forces’ attacks on their towns and villages. The region was under siege for three years, and the Bosnian Serb forces controlled the access roads and impeded international humanitarian aid such as food and medicine.

Image: TRT World

International interventions: the United Nations Peacekeeping Force and the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY)[3]

In response to the rapidly deteriorating humanitarian situation, in April 1993, Srebrenica (along with Zepa and Gorazde) was declared a ‘safe zone’ by the United Nations Security Council. A few days later, an agreement was signed calling for a total cease-fire in Srebrenica, demilitarization of the enclave, the deployment of a United Nations Protection Forces (UNPROFOR) company into Srebrenica, and the opening of a corridor between Tuzla and Srebrenica for the evacuation of seriously wounded and ill people. In March 1994, Bosnian Croats agreed to create the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. In March 1995, Radovan Karadzic, President and Supreme Commander of the armed forces of the self-proclaimed entity Republika Srpska, instructed Bosnian Serb forces to eliminate the Muslim population from the Srebrenica and Zepa enclaves. On July 11, 1995, the Republika Srpska Army, which was under the command of Ratko Mladic, took control of Srebrenica, the safe zone was overrun by the Serbian armed forces.

Thousands of Bosnians took refuge at the UN Peacekeeping Headquarters in Potocari, which were located just outside Srebrenica and under the control of Dutch soldiers. As a pre-condition for entering the safe zone, they temporarily handed over their weapons to UN officials, but that state of affairs only lasted until Serbian soldiers carried out renewed attacks and occupied the headquarters, capturing thirty UN soldiers in the process and threatening to kill them. The peace forces then handed over 8,000 Muslim refugees at the Dutch base in Potocari to Serbian forces in exchange for fourteen captured soldiers. Of those refugees, three hundred men were killed while they were being transported on trucks, and many of the women and children who were taken to other parts of Bosnia died or were killed during the course of their journeys.

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals (IRMCT) tried twenty individuals for crimes committed in Srebrenica in July 1995. They found that the mass killings of Bosnian Muslim men and boys from Srebrenica constituted the crime of genocide. War crimes began to gain visibility, and the number of victims of War began to articulate at an official level. For example, Jean-René Ruez, head of the Srebrenica team at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, put the number of people executed in an ‘organized and systematic process’ at between 4,000 and 5,000, the rest of the victims have died in the fight. Besides, the profiles of the perpetrators also began to gain international visibility. In 2006, a Dutch court ruled that some of the Dutch soldiers serving with UN peacekeeping forces were also responsible for killing three hundred Bosnians in the Srebrenica massacre (1995-2006). The judge who handed down the verdict in the Hague emphasized that those Dutch soldiers should have known that the men taken from the UN peacekeeping camp would be killed because there was evidence indicating that the Serbs were committing war crimes at the time and that the Dutch UN soldiers broke the law by cooperating in the removal of those men from the headquarters. On February 29, 2007, the Hague Court of Justice recognized the massacre as an act of genocide as a beginning. In the end, the court ruled that the Dutch state be required to pay compensation to the relatives of those three hundred men (BBC News 2014; Karon 2001). In February 2006, the International Court of Justice rejected the responsibility of the Serbian State in the genocide. Still, it underlined that the Serbian State did not take ‘all the measures in its power’ to prevent the genocide of Srebrenica. In March 2010, the Parliament of Serbia recognized the Srebrenica massacre as part of the reconciliation attempt by the authorities of the European Union. On January 15, 2009, the European Parliament, called on the Council and the Commission to duly commemorate the anniversary of the act of genocide in Srebrenica-Potocari as a day of remembrance of the Srebrenica genocide, across the EU. The Parliament also invited all Western Balkan countries to do the same. Following this, on March 31, 2010, the Serbian Parliament, with a pro-Western majority with the Democratic Party, recognized the Srebrenica massacre for the first time since the end of the War. Conversely, on May 31, 2012, President Tomislav Nikolic declared during an interview on Montenegrin television that there was no genocide in Srebrenica. » In July 2021, the International High Representative in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Valentin Inzko, decided to use his discretionary power to modify the penal code and prohibit the denial of the Srebrenica genocide and the war crimes that accompany it. This decision led to protests by Serbian nationalists and the blocking of the country’s leading institutions, as well as triggered the conflict with the Muslims in general. While the contribution of political reconciliation efforts to reconciliation at the local and humanitarian level was crucial, it remained questionable. At the same time, many allegations were made about the fair exposure of the perpetrators and the extent of the visibility of war crimes in the Bosnian War. Many claims were made concerning the roles played by international powers, including the UN, and NATO, in the course of the war and the massacres that were carried out in the former state of Yugoslavia, and it has been argued that the crimes committed in Bosnia were widespread. Still, only the Srebrenica massacre has been recognized as an act of genocide by international organizations.

As would be expected, discussions on an intellectual level about the issue have also been quite extensive, but for the purposes of this article, a short overview of the arguments that have been made on the basis of only the two of them. The writings of Herman and Wornan should suffice to reveal the depth of the political complexity of the events that took place.

Image: Business Insider

Polarization around Srebrenica case

Herman has taken up nearly all the topics that surround the Srebrenica case. As he argues, there are several reasons why the Srebrenica massacre garnered so much attention around the world and why it became the primary subject of a tribunal of war crimes. Of those driving factors, the Srebrenica massacre played a unique political role in the re-shaping of the former Yugoslavia by Western powers as the Western media sought to portray the Serbs as « demonic » and the main culprit in the outbreak of violence, especially by highlighting the massacre that took place, as it paved the way for the prosecution of Serbs and Slobodan Milosevic (1946-2006), former president of Serbia and the former Yugoslavia and NATO’s intervention in Serbia in 1999. There were three primary reasons for this turn of events. Firstly, the massacre served as a kind of « medicine » for the political ailments of the Bill Clinton administration as well as a means of meeting the needs of Bosnian Muslims and Croats in the United States. At this juncture, the meeting that was held between Alija Izetbegovic (1925-2003), Bosnian statesman and the first president of independent Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Bill Clinton, 42nd president of the United States, played a key role. Clinton allegedly said that the UN could not intervene in the region unless the Serbs killed at least 5,000 people in Srebrenica. In his mind, Muslims were also responsible for what happened, as they had purportedly let the massacre take place as it served their long-term interests. The Croatian authorities also welcomed such a scenario as it helped them cover up their own crimes of ethnic cleansing carried out against Muslims and Serbs in western Bosnia. Thus, the Srebrenica massacre was transformed into material for « propaganda. »

The second main point here is that bringing the crimes committed by the Serbs before and after the massacre to the forefront served the purpose of propping up the public relations efforts of the UN and NATO forces as they tried to persuade the public that any interventions in Serbia would be justified. Even the ICTY acted as an extension of NATO’s forces as it had been created by NATO itself and placed special importance on the Srebrenica case in ruling against the Serbs. In this way, NATO played an essential supporting role in the strikes carried out on the Serbian province of Kosovo in 1999. Thirdly, the exact number of Bosnian men who were killed in the massacre has never been precisely confirmed. While a reasonable determination has been made on the basis of forensic data, the corpses of Serbian civilians were among the 8,000 people caught up and killed in the conflict, and many of the Bosnians who lost their lives were soldiers, not civilians. Moreover, besides the efforts of the mainstream media, many alternative organizations presented severely distorted photographs and data that placed the blame solely on the Serbs. In following, the ICTY « raised hell » by drawing on the statements of soldiers like Drazen, who were accused of having « no mental faculties » (Herman 2005).

Our aim, however, is neither to justify nor to disprove Herman’s allegations or Wornan’s arguments. All we can do is point out that international power relations were quite effective in either revealing or concealing the crimes that took place. In addition, while it is clear that the crimes that were committed during the War in former Yugoslavia were not prosecuted fairly, this does not mean that the Srebrenica massacre should not be treated as a crime. All the same, Wornan argues that by drawing up such a framework Herman tried to mitigate the crimes committed by the Serbs, distort the available information, and downplay the Srebrenica massacre, thereby disrespecting those who lost their lives there (Wornan 2005). That discussion has provided information that was key for evaluating how « justice » was meted out by international organizations.

Analysis of the Play

The play can be read and interpreted on the basis of the three arguments presented above.

- As past crimes go unpunished, they impose a burden on future generations and create new conditions which can perpetuate impunity.

At the beginning of the play, Kitty Felde provides audiences with background information about the history of Yugoslavia, pointing out that contrary to popular belief, the conflicts that erupted in Yugoslavia can be traced back to clashes that took place long before the 1990s. Although the claim has been made that the region was populated by people with different religious beliefs who had lived alongside one another in harmony since the fourteenth century, the relationship between those communities has been marked by strife for hundreds of years. On June 28, 1389, which was and still is Saint Vitus’ Day,[4] Turkish Muslims and Orthodox Christian Serbs fought each other in the Battle of Kosovo, as a result of which the Turks captured a large part of Yugoslavia. A few centuries later in 1876, the Serbs launched a war, justifying their aggression by citing cases of violence perpetrated by Muslims against Christians, and 12,000 Orthodox Christians were killed near the border with Bulgaria during the conflict. In the course of the battle, Russia provided its Orthodox allies with troops and military equipment, and two years after the cessation of hostilities, Yugoslavia became part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. On June 28, 1914 (again Saint Vitus’ Day), World War I began when Bosnian Serbs issued a declaration of war. The fighting, which resulted in huge losses of life, ended with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on yet another Saint Vitus’ Day and the establishment of the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenians. None of the ethnic communities that were involved, however, were satisfied with the outcome, as Serbs continued to accuse Croats and Croats continued to accuse Serbs of inciting the war.

In 1929, while the founding of political parties was prohibited in the kingdom, conflicts were prevented by way of restrictions and punishments. World War II marked the beginning of a process that would ultimately lead to the splintering of Yugoslavia into smaller territories. Hitler declared that the Serbs were an « undesirable » race alongside the Jews, and when the Croats sided with Hitler, new conflicts broke out. On yet another Saint Vitus’ Day, this one in 1941, one of the bloodiest battles between Catholics and Orthodox Christians took place, resulting in the deaths of approximately 600 Orthodox Christian women and children who were thrown from a cliff. After that last battle, the history of socialist Yugoslavia got started under the leadership of Tito, and the war crimes that had been committed during World War II were covered up. The notion that « religion does not have an important place in communist regimes » was also influential in this regard. A new period began as ethnic and religious differences were brushed aside and communities gathered together under the banner of class struggle, which made it possible for them to get along for a period of time, and in the meantime marriages were sealed between Serbs, Croats, and Muslims. In smaller cities, communities that had historically been in perpetual conflict set aside their differences and not only helped one another but also attended each other’s weddings and funerals. However, as a result of the collapse of communism, those communities witnessed a resurgence of segregation and conflicts resumed. Political disputes gradually became so entrenched that civilians with differing beliefs engaged in hostilities in their daily lives. Members of different parties took up arms and ordinary civilians began committing grave crimes against one another. For all appearances, there simply was no domestic solution, and for a lengthy period of time the international community merely stood aside as a spectator to those crimes.

In 1996, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) was established. Our protagonist, Drazen Erdemovic, was the first war criminal to be punished with a sentence handed down by the ICTY. Because he admitted to his guilt, there was no trial and the punishment was meted out directly. He was released in 2000 after serving his sentence, which initially was ten years of imprisonment but later was commuted to five years (Felde 2007, pp. 28-30).

Image: Encyclopedia Britannica

In the play, by way of this historical chronology we learn about the period of Tito’s rule. Although Drazen’s father complains about the turmoil in Yugoslavia, he always speaks positively about life under Tito, saying that « things got worse afterwards. » We also find out that Drazen’s grandfather was a Croatian who served in the armed forces in World War II.

In the opening scene of Act 1 of the play, Drazen walks into his house after having bought a second-hand television as a birthday present for his mother; he bought the television with the money he’d earned from smuggling people across the border (which at the time was considered a legal and decent business). His mother says that even though the television is second-hand, it’s still fancy enough to show off to her neighbors. While she is happy with the gift, Drazen’s father berates Drazen for not having a steady job, and he even goes so far as to imply that he may have stolen the television. Although the father constantly refers to his son as his « most valuable asset, » we see throughout the play that the father-son relationship is constantly marred by tension. In this scene and the one that follows, we see Drazen with his wife. Through their dialogues, we learn about how difficult it is to « hold down a job » in times of war. Drazen blames his inability to stay employed on the war, saying that his father had it easy because he lived in Tito’s time. His future was already secure, but there is « no future for him [Drazen] » (Felde 2007, pp. 132-138). As a Croat, Drazen is sent to Srebrenica as a mercenary when he signs up for the Bosnian-Serb army, but when he returns, he is a wreck.

According to news reports, the UN peacekeeping force has withdrawn from the safe area that had been established in Srebrenica, and when Bosnian-Serbs occupy the region, thousands of Muslims are shipped off on buses. The commander of the Dutch contingent of UN peacekeeping forces states that the Serbian forces reassured him that Muslims would not be harmed, but subsequent news reports indicate otherwise. Rumor has it that new mass graves were discovered near a forested area outside Srebrenica and that forensic teams have removed 200 dead from the area, which is situated in an abandoned football field.[5]

Drazen visits his father at his house when he returns from the war. In the meantime, his father has already heard the news, and there are members of the press in front of the door. They want to talk with Drazen, as he is one of the soldiers who took part in the events that occurred in Srebrenica. Drazen’s father brushes aside the questions and swears at the reporters. His son is in a state of psychological devastation.

FATHER: Drazen. Drazen, my son, is it really you?

ERDEMOVIC: Hello, Father. (Embarrassed, father calls for mama.)

FATHER: Mama. Mama! Look who’s here! (Mama rushes in and embraces Erdemovic.)

MAMA: Drazen! Thank the Lord. Let me look at you. No bullet holes. No scars. But what is this uniform?

ERDEMOVIC: Mama, I told you. Bosnian Serb.

MAMA (she spits): That’s what I think of your Bosnian Serb uniform. You are Croat. Not Serb. Why don’t you serve in your own people’s army?

FATHER: You remember, Mama. That was last month. This is our son who wears the uniform coat of many colors.

ERDEMOVIC: It’s a job, Mama. That’s all. I had no choice.

FATHER: Choice? You always have a choice, Drazen.

ERDEMOVIC: Do you, Father? Do you really?

MAMA: Don’t start arguing again. Not today. This is a celebration. A homecoming. We must toast our son, home in one piece, thanks be to God. (She finds three slightly chipped glasses and puts them on a tray. Father takes his favorite chair. Erdemovic hovers nearby. He can’t sit still. Suddenly, out of the darkness up center stage, one of his ghosts appears. It is a man in gray, with a burlap sack over his head. Erdemovic leaves the window and returns to where his father is reading the paper.)

ERDEMOVIC: And how are you doing, Father?

FATHER: How am I doing? What am I doing is more like it? Nothing. Not a damned thing! Every factory in the country has stopped making anything useful. How can you export fine furniture when there is not a spring to be had for love or money? And who would want to buy a chair from a country that doesn’t exist anymore? I tell you, this country went straight into the toilet the day Tito died. (Mama hands around the brandy.)

MAMA: Enough politics, Papa. We drink to Drazen, home at last.

FATHER: To Drazen. To my son. Nazdraviti! (They drink. Another ghost appears. Erdemovic shakily puts down his glass and walks to the window.)

ERDEMOVIC: Father. Do you remember grandfather’s war?

FATHER: Your grandfather was not a Nazi sympathizer!

ERDEMOVIC: I never said he was. But Father. In the army, I heard stories I never heard at home. Stories about grandfather’s war.

FATHER: Rumors. Just rumors.

ERDEMOVIC: Perhaps. But such stories, Father. Stories of čiščenje—ethnic cleansing they call it now. The Serbs remember a massacre on St. Vitus Day, near Medjugorje. Six hundred women and children thrown off the cliff near the Franciscan monastery. And the story of a Croatian law student who won a special competition by slitting the throats of more than thirteen hundred Serbs, using a special knife. They say he received a gold watch and a roast suckling pig for his service to the Croatian people.

FATHER: Lies! All Chetnik lies! Your grandfather was Ustashe, it is true. But he was a true patriot. A fighter for the Croatian people, a true crusader for our people and our holy Catholic church.

ERDEMOVIC: I’ve never seen you in church a day in your life.

MAMA: Drazen. Drink your rakia and leave your father alone. He is tired.

FATHER: What do you want from me?

ERDEMOVIC: I want to know what grandfather said about the war. Did he ever follow orders he knew were wrong? Did he ever have to follow orders that made him sick?

FATHER: Your grandfather put the war behind him when he came home. Never talked about it again. That’s good advice, Drazen. You are home now. What happened. Take off that uniform, and go home and kiss your wife.

(Erdemovic starts to say something else but catches a message in his mother‘s eyes. He kisses her on the cheek and leaves the house. He starts to walk home but hears loud laughter and Serbian jukebox music down the street. He enters the smoky bar—full of patrons—and is immediately kissed by Julija his ex-girlfriend. Erdemovic is surprised. They both laugh.)[6]

Poster for the play as performed at Florida State College in Jacksonville. Image:

http://fscj.digital.flvc.org/

We can understand from the conversation above that the members of Drazen’s family have already experienced war, and they are forced to reveal those experiences after their son finds himself caught up in a conflict in which he becomes a murderer. The grandfather never talked about the war he took part in and went so far as to tell his children not to speak of it; all he wanted to do was pick up from where he left off. That burden, however, falls to Drazen’s father. When Drazen says that he wants to learn more about his grandfather’s war experiences, his father reacts by mentioning his father’s advice: Forget about it and move on! However, Drazen’s experiences of war let the « genie out of the bottle, » and his family has terrible wartime memories that are concealed behind heroic stories, as a consequence of which they go unquestioned. Now the son in the family has the option of sharing the same fate as his grandfather. So, what will Drazen decide to do? Follow the path of his grandfather and father?

Another character in the play who bears the brunt of the war is the guard at the international court where Drazen was handed down his sentence after being found guilty. The guard, Elsbeth Van der Kallen, pays special attention to Drazen, whose wife Vesna takes offense when Drazen doesn’t follow her advice (which is almost the same as the advice Drazen’s father gave: « Forget it and move on with your life »). She tears up his letters and sends them back to the prison. Drazen dreams of being reunited with his wife and son, and the guard helps him communicate with her. At the beginning of the play, we are occasionally presented with scenes that include these two characters, but no detailed information is provided about them at first. Towards the end of the play, the guard informs Drazen that she was able to speak with Vesna and that she had come to the prison to visit him. During the course of their conversation, we learn that Elsbeth’s brother was a member of the UN peacekeeping force that was sent to Srebrenica.

ERDEMOVIC: So, Officer Elsbeth Van der Kellen, what’s a nice Dutch girl like you doing in this medieval prison?

GUARD (she shrugs her shoulders): I finished up my army service and needed a job. A few of my pals heard the UN was paying good money for security personnel. Even built a private gym for the guards in the basement of the tribunal building. Sounded interesting, babysitting accused war criminals. So I signed up. End of story.

ERDEMOVIC: Babysitting. Thanks. Where did you serve in the army?

GUARD: No place interesting. But my brother served in Bosnia.

ERDEMOVIC: Really? Where? (There is a pause.)

GUARD: Srebrenica.

ERDEMOVIC: Quite a coincidence.

GUARD: Not really. I requested this duty. I could have stood around in the courtroom all day. But here, at least, they let you talk to the prisoners.

ERDEMOVIC: And you wanted to talk to me? (She nods.) Why?

GUARD: I wanted to know what I would have done if I were in your shoes.

ERDEMOVIC: You would shoot. (She stiffens and is silent.) I’m sorry. Talk to me, Elsbeth Van der Kellen. (She does not respond.) Your brother—what’s his name?

GUARD: Willem. He was a year older than me. Whatever Willem did, I wanted to do the same. He rode his bicycle to Maastricht, I rode my bicycle to Maastricht. He joined the army, I joined the army. He went to Srebrenica to meet Yugoslavs, I’m here in Scheveningen talking to you. (Pause.)Willem was with the Dutch peacekeeping forces guarding the UN safe area.

ERDEMOVIC: He must have felt very proud of himself. Helping to separate men from women, helping to load the buses that brought the men to the killing field.

GUARD: It wasn’t his fault! The Serbs had surrounded Srebrenica. Willem’s garrison had shrunk to four hundred men. Four hundred to protect twenty-five thousand! It couldn’t be done!

ERDEMOVIC: Then the UN had no business promising something it had no intention of carrying out.

GUARD: My brother wasn’t the one who pulled the trigger that killed those people.

ERDEMOVIC: No. Those were my orders.

GUARD (pause): When Willem came home, he and the rest of the Dutch peacekeepers were considered heroes. Some of his mates were taken as human shields, you know. Not Willem. But he was a hero in my father’s eyes anyway. They all were. Until the truth leaked out. Suddenly the Dutch heroes were labeled collaborators and cowards and criminals.

ERDEMOVIC: And what did Willem say about what happened?

GUARD: He never said anything. He never talked about Srebrenica. After a while, he stopped talking at all. He hung around with his mates, mostly. Drinking. He was drunk that night. It was in January. It wasn’t cold enough to freeze the canals, but the roads were icy. Willem slipped on the ice and fell off his bicycle. They found his body in the Mauritskade canal. They say he killed himself. I don’t believe it.

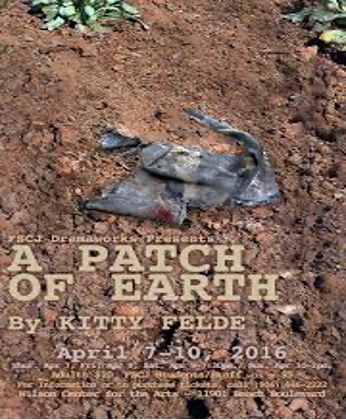

A Patch of Earth: Production at Roger Williams University in Rhode Island (Image:

kittyfelde.com)

Through her story, the guard introduces us to another person who carries the burden of war crimes: Her brother Willem, who had returned from Srebrenica, where he went ostensibly to bring peace. As a war criminal, however, he ultimately was a bystander who facilitated the deaths of numerous people. The attitude of his family (and society) is very similar to that of Drazen’s family (and society). Like Drazen’s grandfather, Willem was welcomed as a hero upon returning home but as time went by, he stopped talking altogether about what he had been through. The fact that society’s attitude towards him shifted 180 degrees and that those « heroes » were now perceived as cowardly collaborators led Willem to commit suicide, as he could no longer bear the social isolation to which he was subjected. As for Elsbeth, she still carries her brother’s burden and suffers as the bearer of an unresolved war.

There is crucial difference between Willem and Drazen here. While Drazen is one of the perpetrators of the crimes that were committed, Willem’s position is more that of a bystander to the crime, as he acts as an agent of the massacre rather than preventing it, and then he does not immediately return to his home country so as to avoid talking about what happened. As a perpetrator, Drazen takes an approach that differs from the stance of his grandfather and Willem, as he accepts responsibility for what happened by revealing his crimes. At the same time, Willem is also a victim of the war, as is Drazen. In war, the roles of perpetrator, bystander, and victim can be interchanged, transposed, and shared, and anyone and everyone can find themselves taking on one of those roles.

2. Societal pressure prevents crimes from coming to light

Mechanisms of societal pressure can prevent the disclosure and admission of crimes by way of advice and/or various types of threats, the aim of which is to convince people to remain silent about crimes that have been committed. In A Patch of Earth, three characters function as mechanisms of social pressure:

- Drazen’s parents

- Drazen’s wife Vesna

- Drazen’s fellow soldiers in the 10th Sabotage Detachment

Drazen’s parents « make speeches » on different occasions throughout the play, telling Drazen to forget about what happened in Srebrenica and to focus on his family. The scene above, in which Drazen expresses his desire to listen to his grandfather’s war stories, can be taken as a model in terms of shedding light on the attitude of his parents. The moment Drazen speaks to the press and confesses to his crimes, his parents are more or less « devastated. » It is as if a peripeteia has occurred, bringing about tragedy for Drazen and his family. First, their son challenged family traditions by not following his grandfather’s example and not heeding his father’s advice. In the end, he chooses to be prosecuted as a war criminal instead of taking on the role of a hero his family can be proud of. At the same time, by exposing and admitting his guilt, he is labeled a traitor; indeed, he receives threats from Serbs. Above and beyond being socially stigmatized, his participation in the war leaves him mentally and physically shattered. The family’s only child is « sick”, and his marriage is in tatters. In his parents’ eyes, Drazen has come to represent a story of « complete failure. »

A Patch of Earth: Drazen and his wife Vesna. Production at Roger Williams University in Rhode Island (Image: kittyfelde.com)

The same holds true for Drazen’s wife, Vesna. Put simply, she finds herself in the position of being the wife of a war criminal and traitor instead of being a woman who is happily married with a child and whose husband returned from the war as a hero. Moreover, the ongoing financial problems that have plagued the couple since they got married only get worse as Drazen is unable to land a permanent job. By this point, Drazen is already in jail, while Vesna is « the most beautiful girl of the [town’s] disco, » as we learn from Drazen’s narrations. Her beauty thus goes to waste as the result of a war criminal’s « obstinacy,” « hallucinations, » or « honesty »— depending on the perspective taken—and she is left to take care of their child.

The societal pressure that Vesna represents takes on different forms in the play. Before Drazen goes to war, we see Vesna as a woman who is fond of her husband and thinks he is a talented and capable man, though she complains that Drazen cannot find a stable job. Drazen winds up enlisting in the army as a mercenary in order to secure a steady income. On the day Drazen returns from the war, conflict erupts between the husband and wife. The moment Drazen steps through the front door of their home, he starts to cry, waking their son Nevin in his cradle, and Nevin begins crying too.

VESNA: Shh. Drazen. Hush. You’ll make Nevin cry as well. (Nevin carries on.) You see? Nevin, you silly boy. Don’t you recognize your own papa? (The child cries even louder.) Hush, Nevin. Shh. It hasn’t been that long. You remember your papa. (To Drazen) He acts as if he’s seen a ghost.

ERDEMOVIC: Maybe he has.

VESNA: You’re talking nonsense. (She touches her hair.) Oh, look at me. No! Don’t look. Here, let me put Nevin to bed while you go tell your parents you are home. Go, quickly! I saved a nice piece of meat for dinner. Maybe I knew in my heart you were coming home today. You are home for good, Drazen?

ERDEMOVIC: Good or bad. I’m home.

In the next scene, we see Drazen awaken from a nightmare. Vesna calms him down, saying that it was only a dream. Drazen gets up to check on his son, and as he sings a lullaby to him, Nevin starts talking to his father, saying that he’s a monster. The scene morphs into a nightmare, and once again Drazen starts talking deliriously in his sleep, murmuring, « The monsters are gone! »

NEVIN: Papa monster.

ERDEMOVIC: Nevin, stop it. I’m not a monster. I’m not. Please believe me.

NEVIN: Papa monster. Papa monster.

ERDEMOVIC: No. No! Shut up, shut up, shut up, shut up! (He shakes the child violently.) You know nothing! Nobody can know what it was like! They turned us all into monsters. All of us! (Erdemovic realizes what he is doing and freezes. He clasps the child to his chest.)

My God, I am the evil ogre! Nevin. Nevin, my sweet pumpkin . . . Please forgive me. You must forgive your poor Papa. Nevin? Can you ever forgive me?

NEVIN (muffled): Papa monster. (Erdemovic realizes that they are not alone. Slowly, Erdemovic turns around and sees a pair of ghosts. He realizes that Nevin sees them, too.)

ERDEMOVIC: My God! (He turns to the ghosts.) Go away! Leave us alone! (But the ghosts stay where they are.) What do you want? My life? My soul?

NEVIN: Papa monster?

ERDEMOVIC: Papa’s not a monster, Nevin. Not so. Don’t believe them. Is it my fault I tried to save my life? Am I to be blamed for that? I did not want to shoot them. (He touches the boy’s hair.) That boy. That one young boy. His hair stuck out on all sides of his head, just the way yours does when you wake up from a nap. He was so scared. So scared he even peed in his pants. Just the way you do, Nevin. He was such a funny-looking fellow. Barely a teenager. And yet, God help me, Nevin, I shot him dead. I shot him dead. I am so very, very sorry, Nevin. Please, please, forgive your papa. (He sobs.)

NEVIN: Don’t cry, Papa. Monster gone. (Erdemovic looks up and notices the ghosts have gone. He again clutches the child to his chest.)

ERDEMOVIC: Monster all gone. Monster all gone. Monster all gone. (Erdemovic staggers back to bed. His murmuring wakes Vesna.)

VESNA: Monsters? What monsters? Drazen.

ERDEMOVIC: Hmm?

VESNA: Drazen, what are these dreams you keep having? Every night.

ERDEMOVIC: Nightmares. Just nightmares. (The ghosts return. There are three of them this time.)

VESNA: Maybe you should talk to someone. Maybe Father Zanic.

ERDEMOVIC: No one. I can talk to no one.

VESNA: You can talk to me. (He sees the ghosts. They nod at him. He swallows.)

ERDEMOVIC: Vesna, what stories did you hear about Srebrenica?

VESNA: A victory for our troops.

ERDEMOVIC: Yes. A victory. Do you know what that means?

VESNA: It means you came home, alive and in one piece.

ERDEMOVIC: Do you ever think about them?

VESNA: Them? (The ghosts are everywhere. Listening.)

ERDEMOVIC: The ones we’re fighting. The ones who won’t come home in one piece because we shot them full of holes.

VESNA: It is none of my concern. You and Nevin are my concern.

ERDEMOVIC: Vesna. What is the worst thing you can ever imagine?

VESNA: Drazen. Don’t play these games.

ERDEMOVIC: The very worst.

VESNA: All right. You are not coming back from the fighting.

ERDEMOVIC: Worse than that.

VESNA: Losing our little Nevin. God protect us all. (She crosses herself, touching her forehead, then chest, then right and left shoulders. Erdemovic rises and walks away from Vesna and the child.)

ERDEMOVIC: What would you say if you knew I had done worse. Much worse.

VESNA: Drazen, you’re scaring me. Stop it.

ERDEMOVIC: Vesna. Look in my eyes. Have I changed since coming home?

VESNA: No. No, of course not. You’re a little thinner. A little browner.

ERDEMOVIC: Look at my hands, Vesna. Can you see the blood on them? (The ghosts rise.)

VESNA: Stop it.

ERDEMOVIC: I killed them, Vesna. I killed them all. Shot them in the back one by one by one. Bang. Bang. Bang. Bang. Bang. Bang. Bang. Bang. Bang. (One by one, the ghosts fall down. The lights fade out as we hear Erdemovic’s litany of bangs. Overlapping his bangs, in the dark, we hear the sound of a gavel pounding three times. Lights up on the courtroom. The « judges » appear upstage. Erdemovic is escorted by his ghosts to the docket.)

The ghosts in A Patch of Earth. Production by the Theatre Workers Project

(Image: theatreworkersproject.org)

Of course, Vesna immediately understands what her husband means, but she doesn’t want to comprehend or know what he’s been through. She merely longs to pick up from where they left off. Unlike the stance his parents take, the attitude he adopts can be assessed in terms of the pressure society puts on him, which takes the form of « understanding what really happened but ignoring it. » At this point, Vesna makes a choice. She is unhappy about her husband’s intention to confess to his crimes and admit his guilt. As such, Drazen’s wife provides no support, and only his ex-girlfriend Julija backs him up.

Day by day Vesna becomes increasingly distant as she pulls away from her husband. Suspecting that Drazen plans to speak with the press, she tries to dissuade him once more from taking such action, but the ghosts stop her. At the end of the play, when Drazen is on trial at the war tribunal, she visits him with the help of the guard. She says she wants a divorce, provided that she testify in his defense.

Vesna’s case represents yet another war tragedy. Her life in the play, which starts with her being « the most beautiful girl of the disco, » concludes with her being a single mother, widowed and poor, a woman whose ex-husband is a murderer. The moral seems to be that if you don’t cover up your war crimes and move on, societal pressure will engulf you. The system requires that you be a part of that mechanism, and if you fail to do so, your life will be ripped apart.

The pressure that society exerts on Drazen through the other criminals in the 10th Sabotage Detachment is predictably the most violent. At first, Drazen’s comrades warn him, saying that he needs to use « appropriate language, » and they suggest that he take advantage of the fact that he is seen as a hero; in that sense, « being comrades in the military » and sharing a « common patriotic destiny » are key points. But the ghosts also hound Drazen. When Drazen’s friends find out that he plans to meet up with the press, they try to stop him by way of brute force and weapons, resulting in Drazen suffering serious injuries.

But at the same time, it is not only Drazen’s ghosts that support him in his struggle with his « conscience. » His former lover, Julija, is the only living person (the others are ghosts) who backs Drazen’s decision to « speak out. » Not only does she set up Drazen’s meeting with the press, she tries to protect him from his armed comrades while also trying to explain to him that his mental distress is actually quite normal. By way of that narrative turn, the play shows us that individuals need support if they are going to disclose the crimes they have committed and confess their guilt. Julija plays a key role in that regard, just as the establishment of a war crimes tribunal for the former Yugoslavia opened the way for those crimes to come to light. If such an official body hadn’t existed, Drazen wouldn’t have been able to confess to his complicity or make his voice heard. In fact, he wouldn’t even have survived the ordeal.

3. International courts and organizations seek out reconciliation not as a means of ensuring justice but rather striking a balance among international powers

In attempting to ensure that justice prevails when war crimes have been committed, international courts and organizations established under the auspices of powerful states may display biases and weaknesses as they set about securing justness. Nonetheless, the establishment of a war crimes tribunal after the Bosnian war represented an important milestone. But did it have the will to see to it that injustices were addressed? Engaging in legal struggles is fundamental to the success of such endeavors, but what kind of tribunals are needed and who should guide their efforts? Is it even possible to establish a court that is independent of international political power games but still robust enough to sanction the parties involved? Answering such questions is far from easy.

On November 29, 1996, the court handling Drazen’s case handed down a verdict, saying, « His soul has found peace, » and the judge noted that he had paid his debts to the ghosts that haunted him after he returned from Srebrenica:

JUDGE: Very well. Mr. Erdemovic. Having considered all of the facts of the case submitted for its attention, the trial chamber sentences Drazen Erdemovic to ten years imprisonment. This judgment shall be enforceable immediately, today, November 29, 1996, The Hague, The Netherlands. The hearing is closed.

BAILIFF: All rise.

ERDEMOVIC: Ten years. Ten years!

BABIC: Calm yourself. Please, Drazen. It is a surprise, yes. But we will appeal. The court refused to take into account the extreme necessity. The fact that you had no choice. That is certainly a strong basis for appeal. (We hear the voice of Stanko.)

STANKO (laughing): You should have kept your mouth shut, comrade.

BABIC: I’ll come see you tomorrow and we’ll talk about our next step. Hold onto your courage, Drazen. This is not the end of our struggle. Goodbye, my boy. (He shakes hands with Erdemovic and joins the rest of the cast in their ghost masks.)

ERDEMOVIC: It is finished. (He turns to the ghosts.) And you. Are you satisfied? I told them your story. I told the world. Is it enough? (The ghosts bow in unison. One by one they turn their « faces » away from Erdemovic. He is truly alone.) Free. I’m free. (The lights slowly fade to black.)

The play summarizes the kind of behavior that is typical of individuals, society, and institutions when war crimes have been committed. Kitty Felde shows us the mechanisms used in war for thinking about models of interrogation and preventing similar disasters, and in that way the play contributes to the language of peace. By analyzing the language and forms of behavior inherent to war and by employing the arts, awareness in civil society can be raised. On that point, the art of theater undoubtedly plays an important role, as it facilitates the telling of human stories and invites us to engage in conscientious contemplation. But in so doing, what ends does it serve? The continuation of the burden of war through its transference to younger generations? The perpetuation of societal pressure that prevents the confession of crimes? The impartial blockage of mechanisms of justice? Discourses of war conceal themselves either periodically or permanently, re-emerging whenever they find the opportunity, thereby consolidating impunity.

At the same time, however, questioning war stories on a human level has the potential to open up a space for the « determination of a conscientious, ethical stance. » Such an approach constitutes the central axis of A Piece of Earth. Recounting the stories of the victims, spectators, and perpetrators of war (as well as the narratives of those who have taken on several of those roles) and exploring individuals’ unique experiences allows us to examine forms of behavior that are not merely limited to political discourses. But perhaps most importantly, that approach may make it possible for us to question the discourses that underpin the waging of war and the generally accepted mechanisms that are utilized to justify conflict and bloodshed, starting with the potential for initiating changes in behavior and summoning the strength to bring about transformations, which all begins with the people themselves in a way that establishes a language of peace.

Bibliography

BBC News. July 16, 2014. « Netherlands ‘partially responsible’ for Srebrenica massacre.” http://www.bbc.co.uk/turkce/haberler/2014/07/140716_hollanda_srebrenitsa

Erdemovic, Drazen. “Litigation indictments.” Archive of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. http://www.icty.org/sid/7463 http://www.icty.org/x/cases/erdemovic/ind/en/erd-ii960529e.pdf

Erdemovic, Drazen. “Case and defendant information.” Archive of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. http://www.icty.org/x/cases/erdemovic/cis/en/cis_erdemovic_en.pdf

Felde, Kitty. 2014. A Patch of Earth. Chesapeake Press.

¬¬¬¬¬__________. 2008. “When news isn’t enough.” Interview with Kitty Felde. Joe Piasecki. http://www.pasadenaweekly.com/cms/story/detail/when_news_isn_t_enough/6256/

__________. Official website. http://www.kittyfelde.com/

Herman, Edward S. July, 7 2005. “The Politics of the Srebrenica Massacre.” http://pokretzasrbiju.org/the-politics-of-the-srebrenica-massacre-by-edward-s-herman/

Institute for War & Peace Reporting. 2012. “Serb Soldier’s Life ‘Ruined’ by Srebrenica Killings.” https://iwpr.net/global-voices/serb-soldiers-life-ruined-srebrenica-killings

Karon, Tony. August 2, 2001. “Lessons of the Srebrenica Genocide.” http://time.com/. http://content.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,169877,00.html

Wikipedia. http://tr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Srebrenitsa_ve_Jepa%27n%C4%B1n_d%C3%BC%C5%9Fmesi

Wornan, Julie. July 18, 2005. “The Politics of the Srebrenica Massacre by Edward S. Herman.” Znet. https://zcomm.org/znetarticle/the-politics-of-the-srebrenica-massacre-by-edward-s-herman-by-julie-wornan/

[1] For more information about the 10th Sabotage Detachment, please see: http://www.hlc-rdc.org/images/stories/publikacije/Dosije_eng.pdf

[2] This section is summarized on the basis of information provided on Wikipedia’s webpages and others providing timeline of the war like www.irmct.org and https://news.un.org/. Since discussions about and interpretations of the Srebrenica massacre vary widely, Wikipedia has issued warnings regarding the objectivity of the data that is given, compliance with reporting standards, and the use of sources.

[3] “International Tribunal for the Punishment of Persons Responsible for Violating International Human Rights in the Territories of the Former Yugoslavia since 1991.” The Tribunal was established as part of UN efforts to prosecute war crimes committed in the former Yugoslavia.

[4] Saint Vitus’ Day carries a particular patriotic significance for Serbians. It is a Serbian national and religious holiday, a slava (feast day) that is celebrated on June 28th according to the Gregorian calendar and on June 15th in the Julian calendar.

[5] Between court scenes, we see snippets from the previous year of Drazen’s life. The play does not have a linear structure; rather, events progress in a stream-of-consciousness manner and through back-and-forth flashbacks. The scenes presented here are excerpts from different parts of the play.

[6] All excerpts are direct quotes from the play.